Why didn't I immediately decide to vaccinate my kids against Meningitis B? Because of the taboo trade-off

We’re naturally uncomfortable weighing up costs and benefits when it could affect the health of our loved ones, but it's perfectly reasonable to think statistically.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I suspect the conversation I had with my wife last week was echoed in many other middle-income households around the country. Here’s the (edited) gist:

My wife: “Did you see that terrible picture in the news of Faye Burdett, the two-year-old who died of meningitis on Valentine’s Day?”

Me: “Yes, unbearable story. She wasn’t that much younger than our daughter.”

My wife: “Her parents released the picture because they’re campaigning for the NHS to make the new meningitis vaccine available to all children. At the moment, only children younger than one are given it.”

Me: “I know, isn’t it disgraceful? And even that was only introduced last year, which means our baby son just missed out on getting it.”

My wife: “But you can get the vaccine privately.”

Me: “Oh? How much does it cost?”

My wife: “About £180 for each child. So should we look into getting it for the kids, do you think?”

Uncomfortable silence. Why uncomfortable? Because: why didn’t we both say “yes” straight away? Why were we even asking the question? This was the lives of our children we were talking about. How could we even think about financial cost when the stakes are so high?

Psychologists talk of the “taboo trade-off”. This means that as human beings we’re uncomfortable weighing up costs and benefits when it comes to decisions that could affect the health and safety of our loved ones. It’s the reason people often end up buying the more expensive baby car seat that promises extra protection in an accident. How would it look to the sales assistant – or, worse, your spouse – if you went for the budget option? What sort of parent are you?

Yet although the trade-off is taboo, it’s hard to avoid. I mentioned middle-income homes earlier because only relatively well-off families could find that kind of spare cash for a private course of vaccine shots for their children. And even the moderately well-off have to think about these things when costs stretch above a certain level. Budget constraints bite on everyone eventually.

When you put your hand in your own pocket to avoid a risk, it’s inevitable that you start to think statistically.

What’s the actual likelihood of the risk I’m paying to avoid? There’s no question that meningitis is a horrific condition. One needs only to look at the heartbreaking pictures and to read the testimony of parents to understand that. But what’s the probability of your own child contracting it?

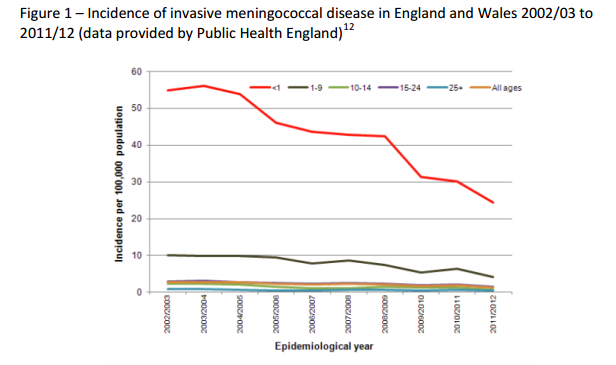

The answer is: extremely low. It affects 25 in 100,000 children aged under one, and that incidence rate has halved from 50 in 100,000 since 2000 (though the reasons for that fall are not well understood). For older children, the risk is lower still.

There is really nothing shameful or inappropriate about thinking about risk in these statistical terms. It’s actually common sense. Proximity to others is a “risk factor” that can lead to meningitis, which is why one strain of the bug tends to break out in student halls of residence. Having an operation can also make someone more susceptible.

If we took the taboo trade-off prohibition to extremes we would not let our children out of the house for fear of contagion. Or we would stop them going to university. Or stop them having even a minor surgical operation.

But, of course, there are other significant countervailing benefits from all those activities which we take into consideration. In the end, we’re practical.

One way of dealing with the taboo trade-off in financial decisions is to outsource it. Health experts on the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation are appointed to advise ministers on which vaccines should be purchased from drugs companies and made available on the NHS. They made their decision not to make the meningitis B vaccine available to all children based on a standard cost-benefit formula.

The cost of offering the vaccine to all young children has been placed at between £150m and £300m. That would have to be paid for, somehow, by all of us. Perhaps the cost will be in higher taxes. Or maybe the bill will be paid in the form of lower-quality care elsewhere, as other budgets are squeezed.

As the GP Dr Sarah Jarvis pointed out earlier this week, the entire mental-health budget for children in the UK is just £700m. Spending more money on a meningitis B vaccine has an opportunity cost. Those funds could be used for something else.

Does this guide us to the conclusion that campaigns such as the one mounted by the parents of meningitis victims are dangerous? If petitions are allowed to override dispassionate cost-benefit analyses by experts, where does that end?

Won’t the most emotive causes tend to receive the scarce resources, squeezing out less heart-rending but no less worthy causes?

Only up to a point. A mechanistic approach to answering all such questions is problematic. The cost-benefit formulae used by expert panels are as much about judgment as they are about science. Like all formulae they depend on inputs. They involve assumptions about the quality of life of victims of diseases over which reasonable people can – and do – disagree.

Young victims of meningitis B, if they survive, often suffer multiple amputations as a result of the septicaemia that tends to accompany it. And there’s a special horror around a disease that can kill a child within mere hours of the first, ambiguous symptoms appearing. What value should one place on avoiding it, rare as it is?

There is no right or wrong answer. It’s entirely appropriate that such formulae are used by the NHS to make decisions. But at the same time, those formulae should not be regarded as sacrosanct.

If, as a society, we decide that we want to crush the incidence of this horrific disease, there’s nothing necessarily irrational about that.

And if a petition signed by 800,000 people is the means by which we transmit that decision, so be it. But let’s acknowledge there’s a bill to pay, too.

Us? We still haven't made up our mind over whether or not to buy the vaccine privately for our children. Nor have I - yet - signed the petition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments