The public wanted something new – we tried to give them it

For the class of ’86, The Independent's first chapter was unforgettable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was an absurd idea. You couldn’t just invent a newspaper out of thin air. In Britain, papers had to have existed since the 19th century; they had to have been owned by lords and barons who had the ear of Prime Ministers; they had to have evolved out of history, with a line on Irish home rule, Appeasement and Suez.

But this was 1986. After 40 years of hardship, there was money in Britain at last. There was something in the air. You no longer had to wait three weeks for the national phone company to fix your line. You could suddenly do stuff: start businesses, make profits, think differently; you could almost be American.

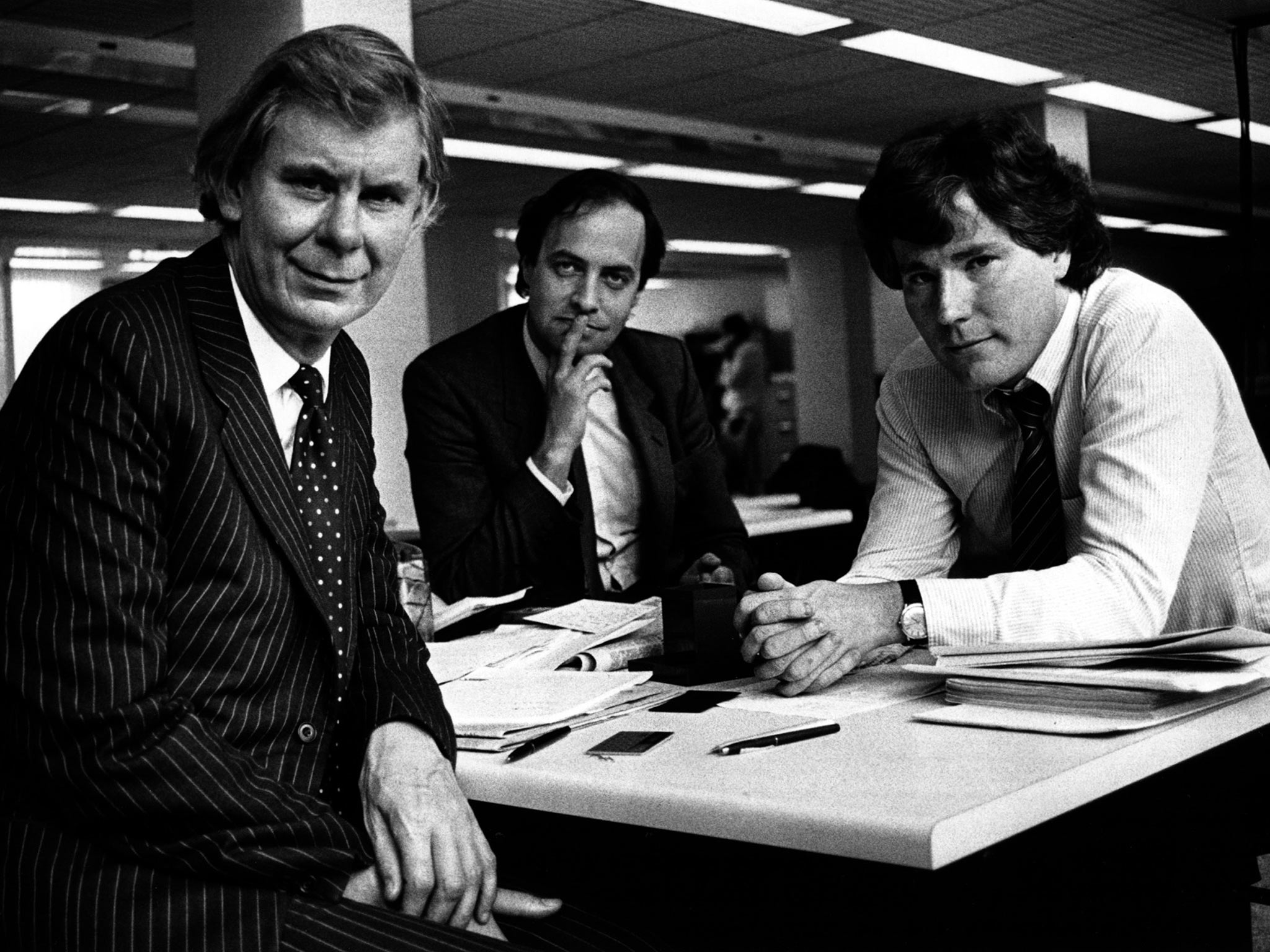

Three likely lads at the Daily Telegraph (still-profitable with a daily circulation of more than one million) sniffed this change and decided to act. The trouble was that the newspaper industry was still locked in old-fashioned labour practices, many illegal, so their job was going to be far tougher than any comparable start-up.

Of the three founders, only Andreas Whittam Smith, City editor of the Telegraph (a big job in Fleet Street at that time) had much journalistic standing. He also knew how finance worked. But it turned out the other two, both then only 34 years old, also had plenty to offer.

Matthew Symonds brought confidence and a brio that kept energy levels high when things wobbled. He could be brash, but his colleague Stephen Glover was emollient; Stephen also had a talent for recruitment, using flattery that could verge on the unbelievable. But it worked. Many journalists, it transpired, felt unloved and undervalued. And the plan was to pay the new staff well. That was a crucial part of the financing. As literary editor, I took a 50 per cent pay rise from my former newspaper job; my colleague in the next office more than doubled his salary.

Andreas professed to loathe Mrs Thatcher, though his spectacular career epitomised everything , for better or worse, that she had changed in Britain – and Mrs Thatcher was the fourth “founder” or at least enabler of The Independent. The fifth was Rupert Murdoch. His self-serving politics and his dummy operation to start an evening paper in Wapping had repelled bien pensant Times and Sunday Times journalists, who became the embryonic paper’s natural prey; but Murdoch also broke once and for ever the print unions’ brutal stranglehold on production. Suddenly, British papers no longer needed to print on Victorian presses; they could use the modern technology that other countries had relied on for years. This alone halved the cost of producing a new paper.

Offices were found in City Road, in central London, a draw for many recruits when the Times and Telegraph had decamped to the East End. There were some big early signings that helped give respectability to the dream. Sarah Hogg, who had been a political adviser as well as an admired journalist, became economics editor. Peter Wilby, the peppery education correspondent at the Sunday Times, came aboard; the medical editor Oliver Gillie came with him. Half the Times news desk pitched up one day, including a young man from Des Moines called Bill Bryson. It became clear that even if the paper failed, as most expected, it would have been a respectable failure, and therefore no disaster to have been part of. I rang up Miles Kington and asked if he’d like to come over from the Times and write a funny column. And he did; and is much missed to this final day.

At great expense a generator was installed to guard against power cuts (this was 1986; you still couldn’t quite rely on the utilities). A full dummy run went on for – was it 10 days? – before the big day in October. The political cartoonist Nick Garland had come from the Telegraph and brought in a designer called Nick Thirkell who produced a paper that looked as though it had been around for years. It looked grand, but just new enough, with its splashy use of photographs. The design and title were not agreed on until close to the launch; until quite late it might have been a tabloid or mid-size called The Nation.

But The Independent was the right name, both Ronseal and resonant. What did it offer? Genuine independence from any proprietorial interference. It had no set political line, but would make its mind up day by day. Andreas was anti-Thatcher, but, I guessed, a Tory at heart; Matthew seemed SDP-ish; Stephen was a pre-war Tory, a sort of Empire loyalist. Most of the staff were Labour voters. It was usually a fruitful tension.

The public was indulgent to the new paper; the triumvirate had accurately – in fact, brilliantly – sensed a desire for something new; and readers responded as though it was already as good as, after a year or so, it really did become. I remember feeling very touched by the generosity of this initial public response; it made us feel we were doing something worthwhile; it made us try to produce a paper worthy of its readers.

The growing success infuriated other newspapers. Simon Jenkins, editor of The Times, told his staff, to our delight, that The Independent, had “parked it tanks on our lawn”. Peregrine Worsthorne at The Sunday Telegraph mocked it for being so egalitarian and wondered if Andreas waited on the post room staff at lunch time. My memory is that Andreas was simply irritated that he couldn’t get away to the Garrick as often as he liked.

There were so many good people. With Glover, Nick Ashford ran a foreign operation of a size and quality that no paper today could afford; and Nick, also much missed, was a hero of the early days. The photography was outstanding, and we even risked an early colour picture – of Tom Phillips’s portrait of Iris Murdoch. On the arts pages, Tom Sutcliffe had hired, among others, Sabine Durrant, Giles Smith, Andrew Graham-Dixon, Adam Mars-Jones, Mark Lawson and – perhaps in those early days the most dazzling of all, Mark Steyn. The books pages, under Robert Winder and Veronica Youlten, had Auberon Waugh (to the dismay of some, the delight of others), Anthony Burgess and a young man called Anthony Lane, later pinched by Tina Brown to become a star at The New Yorker.

The high point of the early days came with another fine hunch by the triumvirate that Saturday was the new Sunday. A hugely extended paper was produced; Alexander Chancellor came back from Washington to edit a stylish colour (in fact more often black-and-white) magazine. The other broadsheets followed; many forests perished in the rush. At this peak, about three years after launch, The Independent, had the widest coverage, the best writers, the clearest values and the best appearance of any paper in England. And some funny bits, too. And it made money.

What happened next is for someone else to tell; but for the class of ’86, the first chapter was unforgettable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments