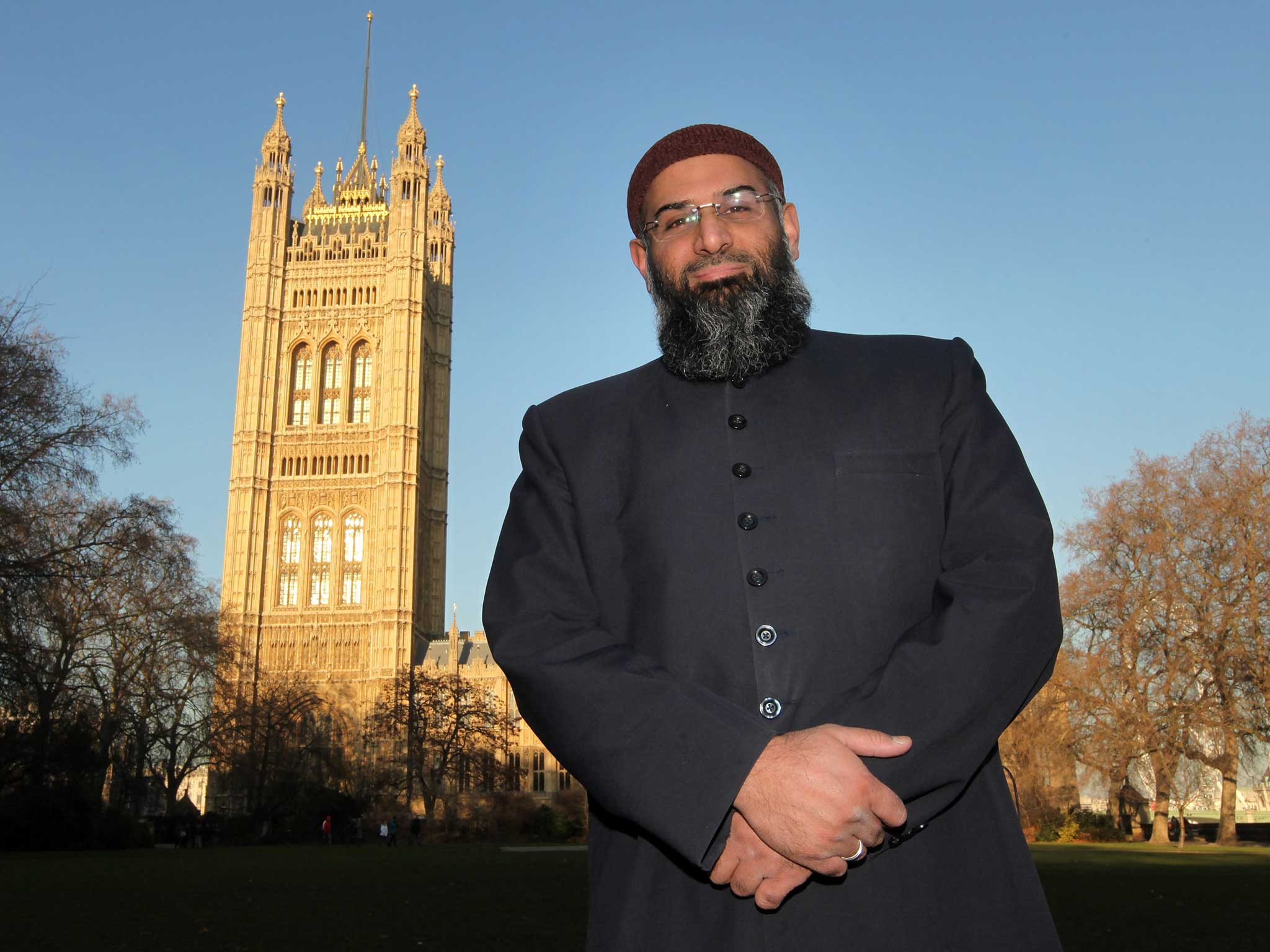

Anjem Choudary's conviction shows that free speech is not without limits

Jailing a person for words they have spoken ought to trouble anyone who believes in liberal democratic values. Yet to protect those very values it is sometimes necessary to be intolerant of intolerance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Security services will be breathing a sigh of relief this afternoon, after it was revealed that Anjem Choudary, smooth-talking preacher of hate, has been convicted of supporting Isis – and of encouraging others to do the same. He is likely to be jailed when he appears at the Old Bailey for sentencing next month.

Choudary has been prominent in Britain for two decades, delivering speeches on street corners, in mosques and via the internet, regularly decrying the perceived grotesqueness of the West and calling for Muslims to establish sharia across the world. Notoriously he was given a platform by the BBC and Channel 4 in the aftermath of the murder of Lee Rigby. The media, said Baroness Warsi at the time, has a responsibility “not to give airtime to extremist voices”.

Yet Choudary was unquestionably clever with the words he used. For years he teetered along the boundary between freedom of speech and incitement to violence. His frequently expressed hope that one day the flag of Islam would fly over Downing Street was presented as simply a kind of evangelism, a prediction that the religion would eventually be the world’s accepted faith.

Sure enough, the news of his conviction will reignite debate in some quarters over the limits of legitimate speech in this country. Freedom of expression is, of course, protected by law. And when the media came under fire for putting Choudary in front of the camera in 2013, their defence was always that it was important to hear extremist views in order that they can be challenged and deconstructed. There is surely a degree of truth in that. If we condemn Choudary for supposedly removing the ability of young Muslims to think for themselves, how should we react when his supporters contend that by silencing him we are fundamentally hypocritical?

In the end, though, no right comes wholly without restriction. Where one competes with another, they must be balanced until the scales tip too far in either direction. In Choudary’s case, the right to free expression could not extend to support for Isis because backing for – and encouragement of – the violence that group engages in ultimately impinges on the rights of those who wish to live without fear of attack or persecution by its fighters. As soon as Coudhary and his co-defendant, Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, made an oath of allegiance to Isis, and pleaded with others to follow suit, the scales were tipped and the police could act.

Jailing a person for words they have spoken ought to trouble anyone who believes in liberal democratic values. Yet to protect those very values it is sometimes necessary to be intolerant of intolerance. Many of those to whom Choudary preached his silver-tongued messages of hatred went to Syria to fight with Isis: in short, he persuaded impressionable young men to kill for a perverted vision of Islam. Ultimately, it feels impossible to ignore the conclusion that jail is the very best place for him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments