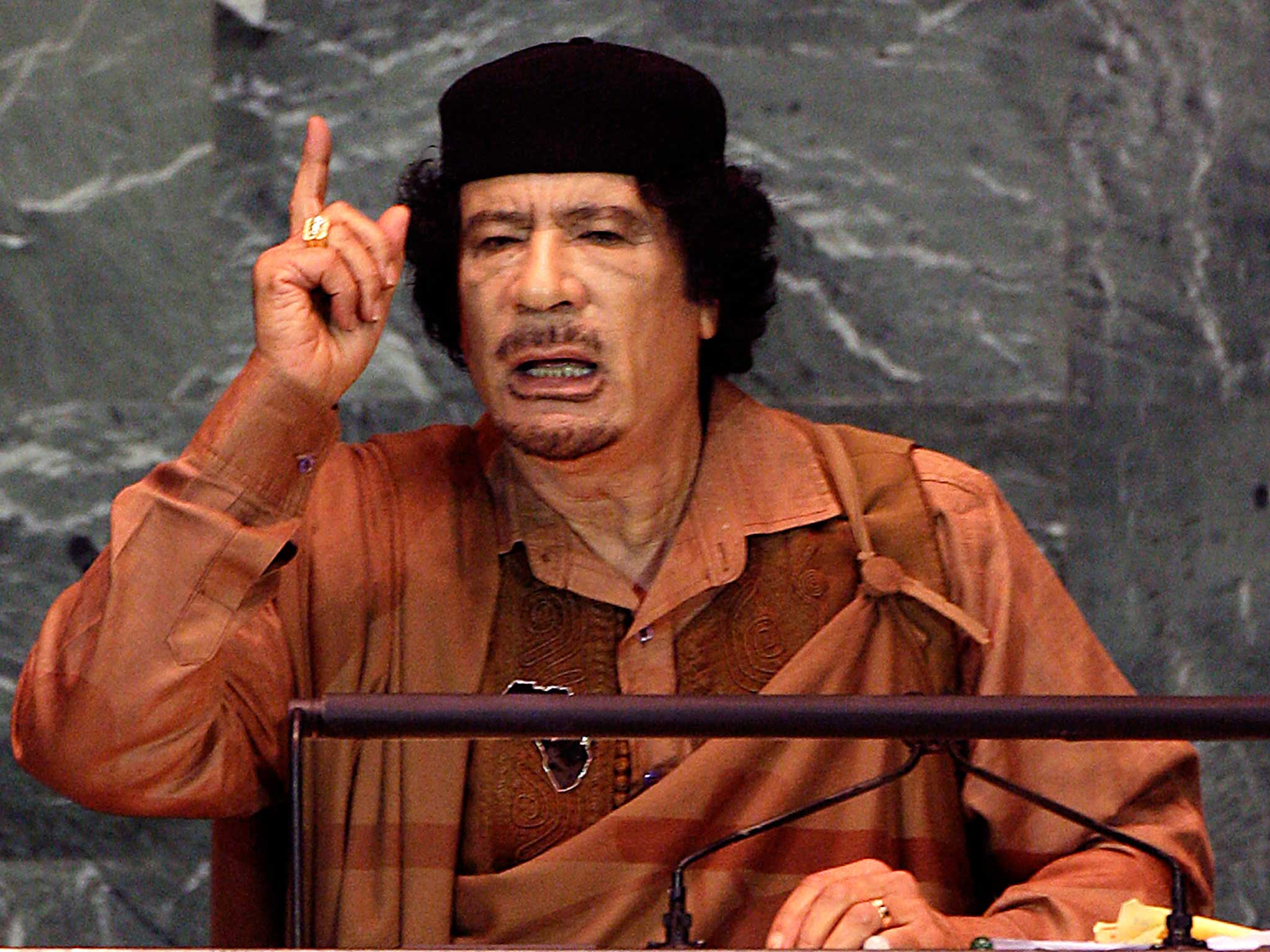

The Arab Spring reported and misreported: foreign intervention in Libya and the last days of Gaddafi

In the fourth excerpt from his new book, Patrick Cockburn recalls the aftermath of the Libyan revolution and the overthrow of Colonel Gaddafi in 2011. Hopes were soon to be dashed, as a barbaric regime gave way to something much worse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I was sceptical from an early stage about the Arab Spring uprisings leading to the replacement of authoritarian regimes by secular democracies. Optimistic forecasts I was hearing in the first heady months of 2011 sounded suspiciously similar to what I had heard in Kabul after the fall of the Taliban in 2001 and in Baghdad after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003. In each of the three cases, there was the same dangerous conviction on the part of the domestic opposition, outside powers and the international media that all ills could be attributed to the demonic old regime and a brave new world was being born.

This seemed very simple-minded: I was very conscious that these police states – be they in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Syria, Yemen or Bahrain – were the product as well as the exploiters of threats to their country’s independence from abroad as well as social, sectarian and ethnic divisions at home. Journalists, who earn their bread by expressing themselves freely, were particularly prone to believe that free expression and honest elections were all that was needed to put things right.

Explanations of what one thought was happening in these countries were often misinterpreted as justification for odious and discredited regimes. In Libya, where the uprising started on 15 February 2011, I wrote about how the opposition was wholly dependent on Nato military support and would have been rapidly defeated by pro-Gaddafi forces without it. It followed from this that the opposition would not have the strength to fill the inevitable political vacuum if Gaddafi was to fall. I noted gloomily that Arab states, such as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies, who were pressing for foreign intervention against Gaddafi, themselves held power by methods no less repressive than the Libyan leader. It was his radicalism – muted though this was in his later years – not his authoritarianism that made the kings and emirs hate him.

This was an unpopular stance to take on Libya during the high tide of the Arab Spring, when foreign governments and media alike were uncritically lauding the opposition. The two sides in what was a genuine civil war were portrayed as white hats and black hats; rebel claims about government atrocities were credulously broadcast, though they frequently turned out to be concocted, while government denials were contemptuously dismissed. Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch were much more thorough than the media in checking these stories, although their detailed reports appeared long after the news agenda had moved on.

Whatever their other failings, the rebels ran a slick and highly professional press campaign from their headquarters in Benghazi. Spokesmen efficiently fended off embarrassing questions and crowds waved placards bearing well-thought-out slogans in grammatical English in front of the television cameras.

My doubts about many aspects of the Libyan uprising, as it was presented to the world, are open to misinterpretation. There was nothing phony about people’s anger against a man and a regime that had monopolised power over them for 43 years. As in other Arab military regimes turned police states, Gaddafi had once justified his rule as necessary to defend Libyan national interests against foreign states and oil companies. But as the decades passed, these justifications became excuses for a Gaddafi family dictatorship that stifled all dissent.

Just how claustrophobic it was to be a Libyan at this time was brought home to me by Ahmed Abdullah al-Ghadamsi, an intelligent, able and well-educated man whom I met by accident after the fall of Tripoli and who worked for me as a guide and assistant. He came from a family and a district in Tripoli that was always anti-Gaddafi, and he had been on the edge of the resistance movement before we met. He was good at talking his way through checkpoints and winning the confidence of the suspicious militiamen who were manning them.

We shared a feeling of exhilaration now that the old regime was gone. I remember Ahmed saying to me with amused exasperation that “books used to be more difficult to bring into the country than weapons”. Seven weeks later, he was dead. He had felt he must play some active role in the revolution rather than just making money, had volunteered as a fighter and was shot through the head in the last days of the civil war.

In the early months of the uprising, a good place to judge the rebel movement was close to the front line in the largely deserted town of Ajdabiya, two hours’ drive south of Benghazi. Here the military stalemate of sudden advances and retreats was very visible: in the restaurant of the local hotel waiters started to ask journalists to pay their bills before they ate. The urgency on the part of the hotel management reflected their bitter experience of seeing journalists – their only customers – abandon meals half-eaten and leave, bills unpaid, because of a sudden and unexpected advance by the pro-Gaddafi forces.

On the outskirts of Ajdabiya, rebel pick-ups and trucks, with heavy machine guns welded to the back, rushed backwards and forwards, the speed of their retreats so swift as to endanger any camera crews or reporters standing nearby. I had an ominous feeling, as I drove about Ajdabiya, Benghazi and the hinterland of Cyrenaica, that all would not turn out well. “It would take a long time to reduce Libya to the level of Somalia,” I wrote on 13 April 2011, “but civil conflicts and the hatreds they induce build up their own momentum once the shooting has begun. One of the good things about Libya is that so many young men – unlike Afghans and Iraqis of a similar age – do not know how to use a gun. This will not last.”

Nor did it. But it was not the militarisation of Libyans that broke the stalemate but the intervention of Nato air forces. The shape of things to come was already becoming clear: on 22 May I described how flames were billowing up “from the hulks of eight Libyan Navy vessels destroyed by Nato air attacks as they lay in ports along the Libyan coast. Their destruction shows how Muammar Gaddafi is being squeezed militarily, but also the degree to which the US, France and Britain, and not the Libyan rebels, are now the main players in the struggle for power in Libya. Probably Gaddafi will go down because he is too weak to withstand the forces arrayed against him. Failure to end his regime would be too humiliating and politically damaging for Nato after 2,700 air strikes. Once he goes, there will be a political vacuum that the opposition will scarcely be able to fill. The fall of the regime may usher in a new round of a long-running Libyan crisis that continues for years to come.”

By August, Gaddafi had fled and I was in Tripoli touring the abandoned palaces, villas and prisons of the ruling family that had so recently abandoned them. I tried not to be a professional pessimist, pointing out hopefully that, unlike Iraqis and Afghans, Libyans had a high standard of living, were well educated and were not split by age-old ethnic and sectarian divisions. But even this upbeat summary concluded plaintively as I added: “All the same, I wish the shooting outside my window would stop.”

It never really did stop. Tripoli was full of checkpoints that reminded me of Lebanon during the civil war of 1975 to 1990. The arrival of the new transitional government from Benghazi did not fill me with confidence since one of its first measures was to announce the end of the ban on polygamy introduced by Gaddafi. I had periodically visited Tripoli in the 1980s and 1990s and had noticed that, as in the oil states of the Gulf, most of the work was done by migrants from poor countries that were Libya’s African neighbours. To find out what was happening in Libya at that time, I would go for a walk in the marketplace and fall into conversation with bored Ghanaians or Chadians, all migrants on their day off, who would tell me more about the real state of the country than any Libyan official or Western diplomat.

But with the fall of Gaddafi, all black faces were regarded with suspicion by the new rulers as likely supporters of the fallen leader. They were often accused of being “pro-Gaddafi mercenaries”, interrogated, jailed and occasionally murdered. Life for the migrant and indigenous black population was to get steadily worse in the coming years as Libya disintegrated, and by 2015 Ethiopian and Egyptian Christians were being executed by Islamic State’s Libyan clone. Meanwhile, the West Europeans were reaping what they had sown by destroying the Libyan state: migrant labourers, who had once found jobs in Libyan markets and building sites, were now risking their lives as they sailed in over-crowded and unseaworthy boats across the Mediterranean in a desperate attempt to reach Europe.

My fears about the “Somalianisation” of Libya, first expressed in March 2011, had turned out to be all too true. Four years later, Libya was ruled, in so far as it was ruled at all, by two governments, one based in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk, while real authority lay in the hands of militias that fought each other for power and money. Demonstrators in the streets of Tripoli were shot down by anti-aircraft machine guns whose large calibre bullets tore apart the bodies of protesters; Tripoli International Airport was destroyed in fighting between rival militias; torture was ubiquitous; and the country split between east and west. For all his quirky personality cult and monopoly of power, life in Libya under Gaddafi had not been as bad as this. The demonisation of Gaddafi had an unfortunate effect in ensuring the opposition had no real programme other than his replacement by themselves.

Libyans were relieved at the end of 2011 to find that they no longer had to study the puerile nostrums of Gaddafi’s Green Book – in the knowledge that if you failed the exam devoted to this work, you had to retake the entire course. But Libyans also found to their horror that they had lost a haphazard but functioning state, and with it personal security in the sense of being able to walk the streets in safety. They were now at the mercy of predatory militiamen who were paid out of Libya’s diminished oil revenues. I remember a fellow journalist upbraiding me politely in 2011 for stressing the failings of the Libyan rebels, saying: “Let’s remember who are the good guys.” A few months later, as the revolution turned sour, good and bad in Libya were ever more difficult to tell apart.

This was a common experience in the six countries most affected by the Arab Spring. By 2015, three of these – Libya, Syria and Yemen – were being ravaged by warfare and two others – Egypt and Bahrain – were ruled by authoritarian governments more brutal and dictatorial than anything that had gone before. Only in Tunisia, where it had all started, did an elected civilian government cling on, though increasingly destabilised by massacres of foreign tourists by Isis training camps in Libya. The Arab Spring had turned into the age of jihad.

This is an extract from ‘Chaos and Caliphate: Jihadis and the West in the Struggle for the Middle East’ by Patrick Cockburn, published by OR Books, price £18. The discount code readers can use for 15% off ‘Chaos and Caliphate’ is: INDEPENDENT

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments