The Great British water crisis: From Thatcher’s privatisation pipe dream to busted flush

In theory, Thames Water is owned by some of the wealthiest bodies on Earth, writes Chris Blackhurst. In reality, a sector that had the slate wiped clean 34 years ago by Margaret Thatcher is in hock today to the tune of £65bn, and the leaks Sunak is trying and failing to stem are spreading

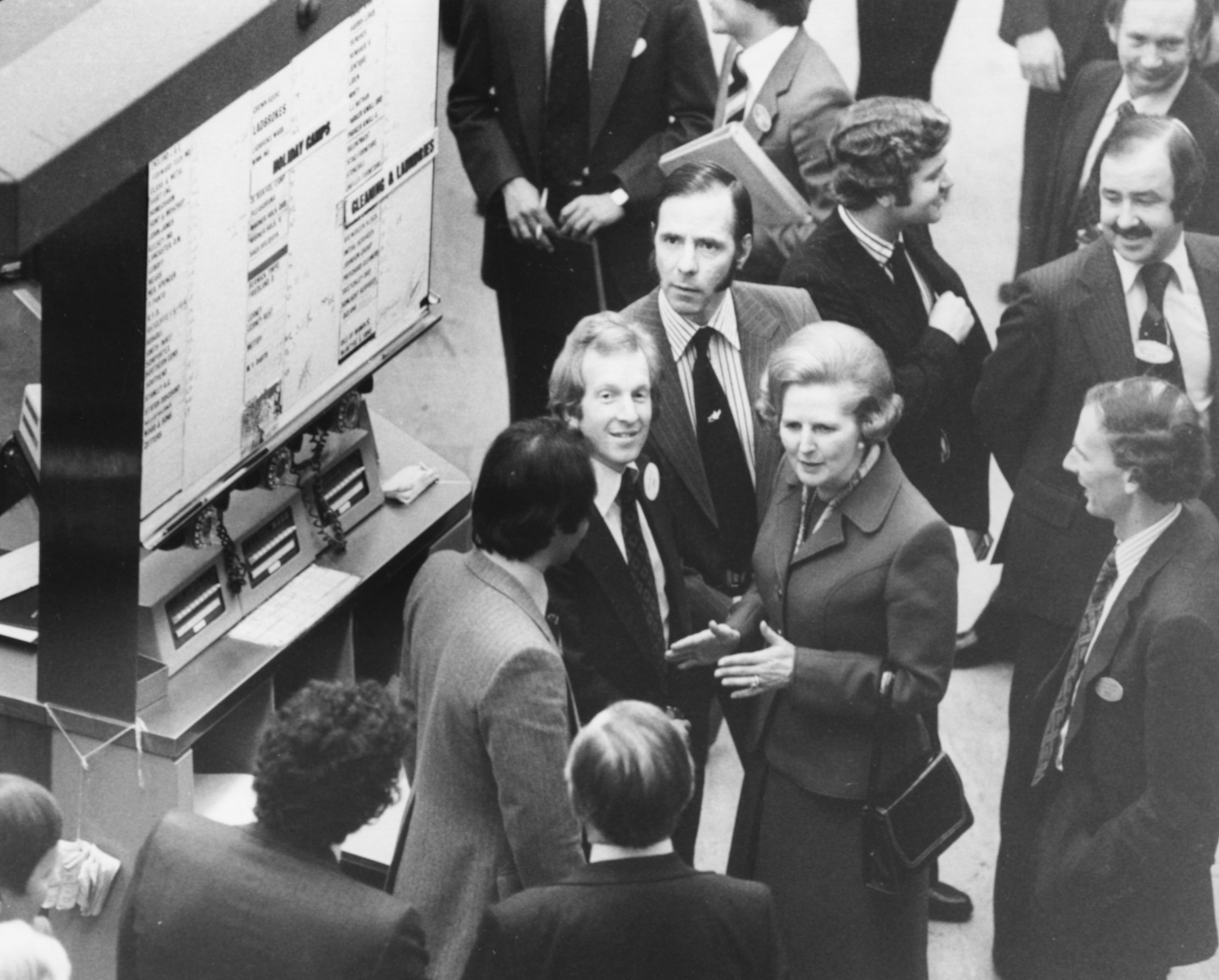

Back in the late 1980s, Mrs Thatcher was in her pomp. She was sweeping everything before her, beating the unions here, breaking up the vast state apparatus there.

In the City, which I remember well, there was a sense of bonanza, of striking the jackpot. I recall being in a watering hole one evening off Moorgate, the door flinging open and a pinstriped character rushing in, clutching piles of documents, shouting: “Fancy some stagging, boys?”

Everyone gathered around him, grabbing the papers and waving them aloft. They were prospectuses for one of the government privatisations – and “stagging” was the practice of buying shares on flotation and selling them immediately for an instant profit.

The stock, as the drinkers knew, was a bargain. So anxious were Thatcher and her colleagues to dismantle the public sector that they were clearing the debts, writing them off – and flogging the industry cheaply.

So, in the case of the regional water suppliers, this meant them coming to market without any borrowing (£6.5bn of taxpayers’ money was given to them to wipe out their debts). To make it easier still, they were sold for less than their actual value: hence the opportunity for some serious City money-making, or “stagging”.

The idea was that the providers of essential services would no longer be a burden on the public purse; that henceforward, water entering and leaving a property would be the responsibility of someone else.

In theory, Thatcher wanted to include in the owners an army of private investors, to promote her ideal of a share-owning democracy – but they soon gave way to the major institutions. Again, ministers said the new utilities would always remain in British hands, but that notion fell into abeyance as the overseas financial powerhouses muscled their way in.

Still, it was meant to be a bright new dawn for an industry that relied on Victorian piping and plant, that had not moved with the times, not adjusted to improvements in housing and increases in population. Michael Howard, the minister in charge of flogging water (even writing that about something so universal seems perverse), pledged the companies would be embarking upon “the biggest programme of sustained investment in their history”.

Currently, my eldest son lives in Whitstable, in Kent, and he can’t swim in the sea – part of his reason for living there – because the water is polluted with raw sewage. Relatives of mine in Cumbria similarly dare not cool down with a dip. Two places, hundreds of miles apart, affected by one identical problem. It’s a situation that is replicated all over these islands.

The water companies have been investing, more so now there is a public outcry, but it is not enough. What they’ve also been doing is borrowing ever-increasing amounts – fine when rates were low – and ensuring their shareholders receive regular dividends (£1.4bn last year alone), not to mention payments in salaries and bonuses to their executives. Their bills to customers have risen, too.

A sector that had the slate wiped clean 34 years ago is in hock today to the tune of £65bn. One large slug of that, £14bn, is owed by just one company. Today, that firm, Thames Water is on the brink, struggling to service a debt mountain in the face of rising interest rates.

Its chief executive has resigned – and it is touch and go whether Thames Water is temporarily returned to public ownership before being sold on, back into private hands.

The firm is two years into an eight-year plan to tackle water leaks and reduce sewage pollution. But its leaks are at a five-year high.

In theory, Thames Water is owned by some of the wealthiest bodies on Earth, including the China Investment Corporation, an arm of the Chinese government, Infinity Investments, part of Abu Dhabi’s Investment Authority, a large Canadian pension fund and the UK’s Universities Superannuation Scheme. They stumped up an extra £500m only three months ago and Thames is asking for another £1bn. In reality, they’re reluctant to inject more, staring into what seems awfully like a bottomless pit.

These shareholders in essence aren’t the problem. Arguably, Thames Water’s woes really set in when it was owned by Macquarie, the Australian bank. Then, the company ran up billions in debt while paying out £2.7bn in dividends. Macquarie sold out in 2017, but the damage was done.

The issue the government faces, however, is that Thames Water is not alone. A “handful” of other water companies are said to be in similar difficulties.

What has driven matters to a head is the need for transformative infrastructure improvement. Those costs could not be passed on to the consumer, as already high bills would head to stratospheric levels and provoke almighty rows, with bankruptcies and people being denied access to water. They paid for the investments by borrowing. Now, they are feeling the pinch – same as many mortgage-holders, same as many businesses.

Worse for Rishi Sunak and his team is the thought that for water, read: railways, roads, gas, electricity, council services, the NHS and schools. The nation’s infrastructure has been creaking across the piece for decades.

Refurbishments and additions were not carried out when they should have been; the privatisations, whether by direct sell-off or public-private partnership, did not lead to sustained investment, on the sort of scale that Howard pledged.

The “austerity” years following the 2008 banking crisis only served to widen the gap. Now, the sums entailed to make the necessary advancements are colossal – and Sunak or whoever is in charge (this is not a conundrum that is going to be resolved in one go, it is ongoing) is left with one enormous headache.

Thames Water is likely to be the first, of what could be several or of many. Those heady, crazy, party-like-no-tomorrow (and yes, greedy) days of 1989 appear very distant indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments