I gave up speaking Arabic at the age of 13 because of the War on Terror

Fourteen years on from Britain’s decision to invade Iraq, the negative connotations of the Arabic language have become worse. It’s upsetting, because contrary to its associations of barbarism, it is actually a deliciously camp language full of hyperbole and proverb

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Britain invaded Iraq in 2003, I was a 13-year old schoolboy in London. My parents, both Iraqi and raised in Baghdad, were understandably more affected by the war than I was. Everyday, the news relayed images of bombs destroying our homeland, and my mother and father feared constantly for the safety of relatives. When we once got through to my grandmother in Baghdad, we heard the house literally shake from the tremors of the Western onslaught.

This was also the year I stopped speaking Arabic for good. Now my Arabic was never that proficient, but my childhood was surrounded by it, and I was always working to develop it. I was proud to have Arabic in my daily vernacular. But as the terror-fuelled-“war-on-terror” escalated during my adolescence, I developed an aversion to the language. In fact – I grew ashamed to be near it. When my mother called at me from the school gate in our native tongue, I’d physically cringe around my classmates. When waiters watched us squabble in Arabic, I’d instantly retreat behind my menu red faced. I became so hostile around the language, that when my weekly Arabic tutor set me assignments in lessons, I’d respond only in French. It wasn’t long before said tutor bid me au revoir.

Why the decisive rejection of my cultural routes? Well, coupled with the Western demonisation of the Middle East, I was also at a school – of mostly white students – where I was bullied for being gay. To prevent more blows to my self-worth, I wanted neither of the deepening associations with the Arabic language – being a villainous other or a weak war victim. In fact, so co-opted in the Western fear mongering against the Middle East, I also denounced Islam, and at one point screamed, “I AM NOT ACTUALLY ARAB LIKE YOU” at my parents.

In effect, I was socially reproducing racism and Islamophobia inside my own home, which caused traumatic rifts between me and my parents (cheers Blair). Fourteen years on from Britain’s decision to invade, the negative connotations of the Arabic language have become worse. If a passenger is reading it on the tube, there’s usually an empty seat beside them. If someone’s on a bus speaking Arabic, people spy on nervously. And the Islamic equivalent to Amen –“Allahu Akbar” – is seen as an Isis staple rather than a historic term of praise.

Cultural representation has a lot to answer for here. Characters speaking Arabic on screen are usually villains who need to be destroyed so that the plot can resolve. Take Howard Gordon’s TV shows like Homeland or 24. Or FX’s Tyrant about a Middle Eastern dictatorship, in which the only saviour – who is in fact Arab in the script – is played by a white American. The marriage of malice and Arabic was pursued quite literally in Thomas Bidegain’s Les Cowboys, a racist and misogynistic story about a French father on a mission to rescue his daughter from the Middle East. When he discovers Arabic text in her diary for the first time, the soundtrack morphs into something more suited to Jaws.

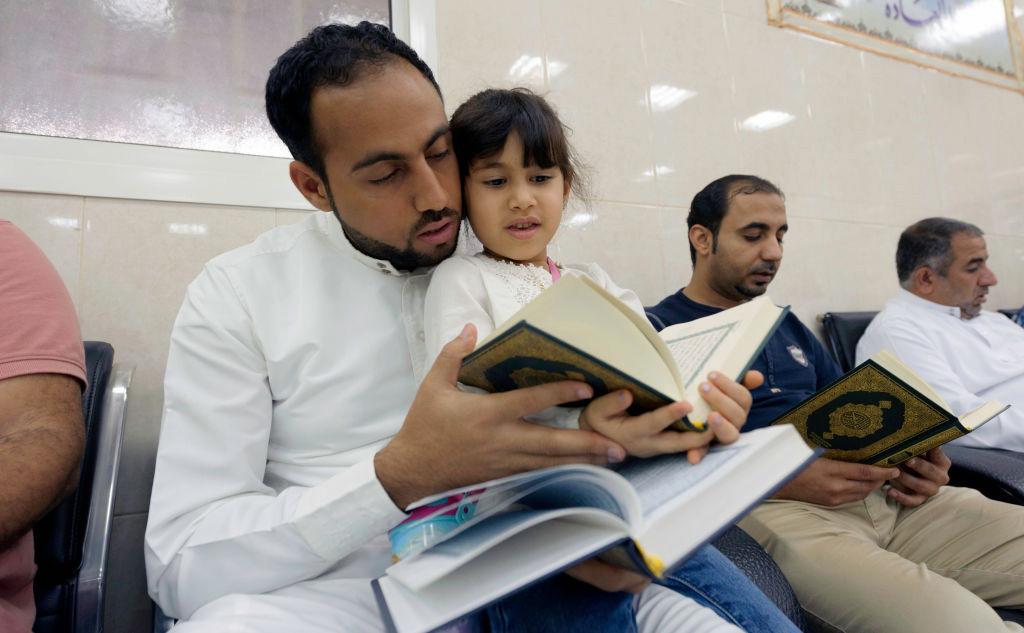

It’s upsetting, because Arabic is one of the most graceful and poetic languages there are. Contrary to its associations of barbarism, it is actually a deliciously camp language full of hyperbole and proverb. The most common pronoun used for friends and family, “hayatti” or “habibi,” mean “love of my life,” or “my sweetheart.” One of my favourite Arabic proverbs, which would feel at home coming out of Ru Paul, is, “a secret is like a dove – when it leaves my hand it takes wing.” And whilst calls to prayer are now felt to be an Islamic call to arms, it was in my early childhood a soothing and paternal lullaby.

Today, I’m angry at the Western ideologies that taught me to demonise my own language. As I move forward, I am slowly repairing my relationship with Arabic, which has love in its very grammar, in its beautifully calligraphic form. The only barbaric language we need to eradicate is that of extremism; for this can develop in any culture, and its idiom is only hate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments