After three months of debilitating strikes, what have we learnt?

The NHS pay deal is hardly a triumph for Sunak: waiting lists are even longer because of his foot-dragging, writes Andrew Grice

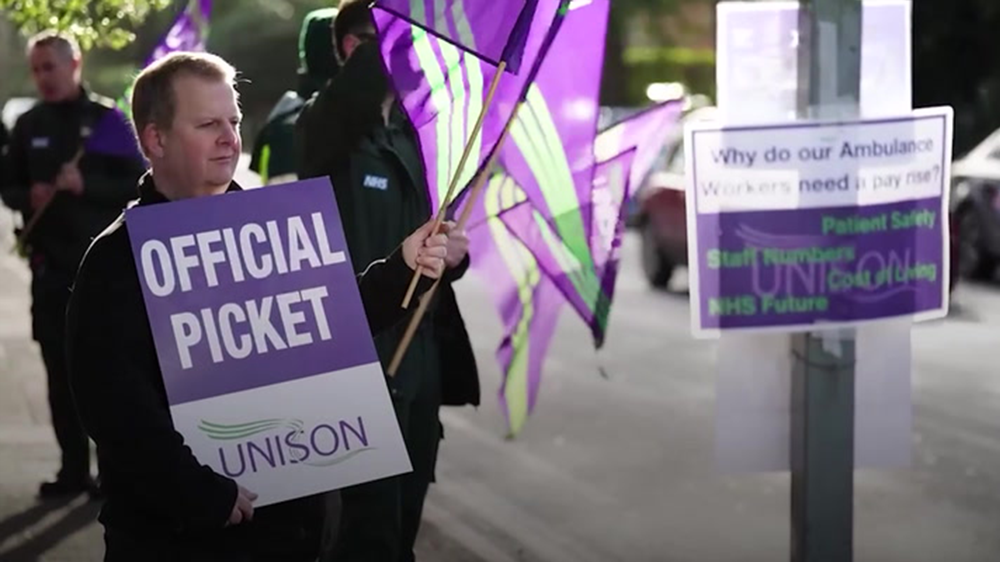

The proposed pay settlement for 1.2 million NHS staff, including nurses and ambulance workers, is welcome but could and should have happened in early January.

Whitehall sources tell me that Steve Barclay, the health secretary, wanted a deal then like the one that has now been announced for England: a one-off payment worth 2 per cent of salary plus a bonus of at least £1,250 for the 2022-23 financial year and a permanent 5 per cent uplift for the year beginning next month. The agreement has to be accepted by union members but their leaders, with the exception of Unite, are recommending it.

Two months ago the health secretary’s move was blocked by the Treasury, and Rishi Sunak sided with Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor. “Steve Barclay could see that we would need to make a one-off cost of living payment for the current financial year,” one insider said. “This could have happened earlier.”

Sunak allies are trumpeting his role in last night’s breakthrough as another sign of his calm, forensic, pragmatic style of government, which has momentum after genuine successes on the Northern Ireland protocol, his love-in with Emmanuel Macron and the Aukus defence pact with the US and Australia. Tory MPs hope that an end to NHS strikes will remove one sign that “Britain isn’t working”, a pervading sense some fear will cost their party the next election by underlining Labour’s “time for change” message.

But the NHS pay deal is hardly a triumph for Sunak: 140,000 operations or appointments were cancelled during the dispute and waiting lists are even longer because of his foot-dragging.

Ministers made a big miscalculation: that public support for the strikers would wane over time. It didn’t. As I reported, they played for time in the hope a more generous offer for the 2023-24 year would end the 2022-23 dispute. An improved short-term fiscal outlook helped Hunt sanction the one-off payment, and the Budget forecast that inflation will fall to 2.9 per cent by the end of this year meant union leaders viewed a 5 per cent rise as a reasonable deal. Loyalist Tory MPs are calling it “a draw” but the government gave most ground by dropping its refusal to reopen its 4 per cent pay offer for 2022-23.

The NHS agreement should provide a platform to end the strikes by teachers. On 17 March the National Education Union and government announced a period of intensive negotiations during which no more strikes will be called. But ministers might offer a less generous pay rise to groups such as civil servants, which could mean disruption at the Passport Office ahead of this summer’s holidays. The junior doctors will be offered the same rise as other NHS workers but there is a huge gulf between them and the government over their demand for a 35 per cent increase.

What are the lessons from three months of debilitating strikes? The Tories should not lazily assume the public will oppose strikes when workers have clearly suffered a “lost decade” of real terms pay cuts. The trade unions, regularly written off after their membership halved from 13 million since the previous winter of discontent in 1978-79, showed they are still in business. The health unions were wise to make their campaigns about the state of the NHS as well as pay, which boosted their public support. (Junior doctors should take note.)

The government needs to restore confidence in the pay review bodies, which have been exposed as far from “independent” as ministers claim. The bodies are rigged in the government’s favour: ministers set their financial limits and tell them to take account of the Bank of England’s 2 per cent inflation target – an insult to workers during a cost of living crisis with inflation running at more than 10 per cent.

Some unions will now boycott the review bodies, preferring the direct negotiations which secured the NHS deal and saw firefighters win a big rise without going on strike.

Ministers must ensure the NHS settlement is properly funded. Although they insist frontline services will not be affected, it’s not clear how the £2.5bn cost will be met and there’s talk of our old friend “efficiency savings”, which could impact on services. The deal should be fully funded by the Treasury and not from existing health or other departmental budgets.

Finally, the government should provide extra money to increase the pay of our again forgotten social care workers, who typically earn £1 an hour less than healthcare assistants. Instead, there are worrying signs the government might dilute a plan to “invest” in the social care workforce by at least £550m.

If carers fall further behind after the health workers’ deal, even more of them will switch to the NHS, deepening the crisis in a sector with 165,000 vacancies. In turn, this would put yet more pressure on the health service, just when the long overdue pay deal finally gives it a chance to move forward.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments