Sorry George Osborne, but an Anglo-German alliance is not likely

The first problem is that, when all is said and done, the Germans don’t really like the Anglo-Saxons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

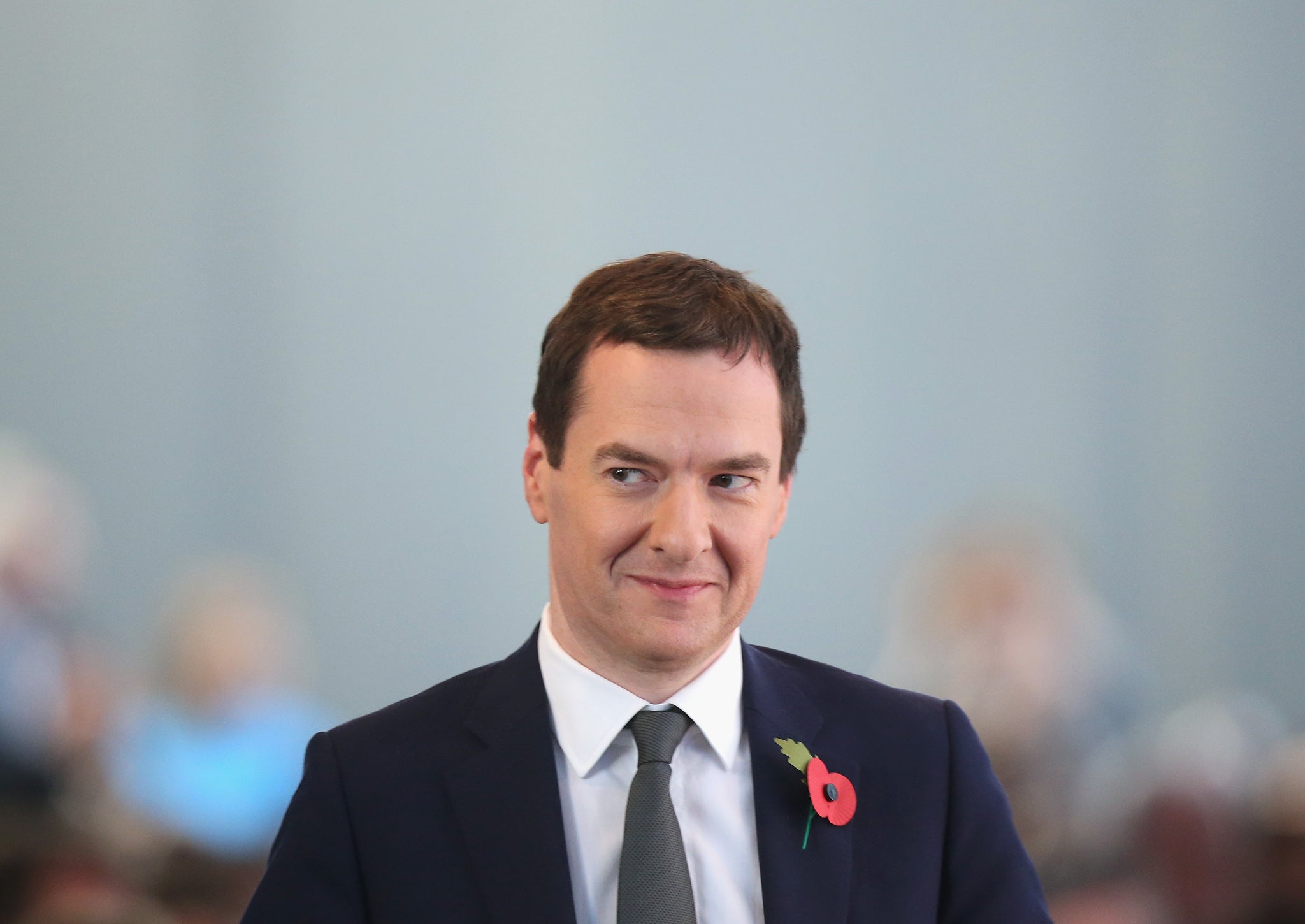

Your support makes all the difference.In the speech George Osborne gave in Berlin this week in which he outlined some of the changes in the operation of the European Union that Britain would require if we were to remain a member, he said something that I found even more interesting, though it has received less attention.

He argued that Britain and Germany had a responsibility “to show economic leadership in Europe”. For there is a simple truth, he went on: “We are Europe’s engine for jobs and for growth.” If this was not just a rhetorical flourish, it was a striking sentiment.

France and Germany, not Britain and Germany, have run the EU and its predecessor bodies since the early 1950s. One of the many oddities of Britain’s 40-year membership is that throughout, we have been subordinate first to the leadership of France, with Germany in the background, and then to Germany with France as second string. When President Vladimir Putin, for instance, wishes to discuss Ukraine with European leaders, he invites the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, and the French President, François Hollande, to the Kremlin. Or he flies to Paris to meet them. David Cameron is nowhere to be seen.

We are dealing here with the “German Question”, a fixture in European politics for at least 150 years. It is still with us, as the many comments on Germany’s policy in the Greek debt crisis illustrated. The original German question centred on the final unification of Germany in 1871 following revolts all over Europe in 1848. A collection of small German-speaking states was replaced by a single colossus, which called itself the German Empire.

The previous year, France had rashly declared war on Prussia and was roundly defeated. So unification was proclaimed by a victorious Germany in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. Talk about humiliating your enemy. In Versailles, German princes toasted Wilhelm I of Prussia as German Emperor. So the German question has two faces, France’s weakness as much as Germany’s sheer strength, economic as well as military. All this was illustrated again as Nazi Germany overran France in 1940.

The result has been that every major stage in the construction of the EU, which began in 1950, has required secret negotiations between France and Germany in which France has sought to extract concessions from Germany – while she still could – to still her fears of German might. Thus during the negotiations that created the original European Economic Community, or Common Market, the writer François Duchêne noted that “throughout, the French and Germans were preoccupied primarily with one another”. Their private deal was that France would open her markets to German exports in return for French farmers’ gaining protected outlets for meat, dairy products, grain and sugar beet.

Then, following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, the then French President, François Mitterrand, came to see that a single European currency was the only way for other European countries to regain the sovereignty they had lost to Germany – and in particular to the German central bank, which maintained a super-strong Deutschmark. Hans Kundnani tells in his recent book The Paradox of German Power how in September 1989, the French President remarked to Margaret Thatcher that “without a common currency we are all already subordinate to the Germans’ will”. In due course, this deal was enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992.

To stake a claim to a partnership role with Germany, the Chancellor of the Exchequer emphasised that the two of us were the only successful large economies in Europe. Had we not both expanded by the same 13 per cent since the economic crash seven years ago while the rest of Europe has grown by just 4 per cent? Had we not together created more than three million jobs while employment had been lost across the rest of Europe? Particularly in France, he might have added. So assuming for the moment that the Government can negotiate a deal with the EU that it is willing to recommend to the British people and we vote to remain, what would be the likelihood of an Anglo-German partnership’s replacing the Franco-German duo that has managed European integration for more than half a century?

The first problem is that, when all is said and done, the Germans don’t really like the Anglo-Saxons. There was an unfortunate incident concerning Konrad Adenauer, the first post-war Chancellor of Germany, which took place soon after the war had ended and the victorious Allies were occupying Germany. Adenauer was then the Mayor of Cologne. The British summarily dismissed him for incompetence. He was nearly 70 at the time. He had first been appointed to the post in 1917 and held it until 1933, when the Nazis fired him. He is supposed to have said afterwards that his three chief dislikes were “the Russians, the Prussians and the British”.

Then, to take a quite different example, Germany drifted away from the United States and Britain in the early 2000s. Kundnani reminds us that Chancellor Gerhard Schröder launched his campaign in the general election of 2002 with a speech that was unprecedented in the history of post-war German foreign policy. In it, he spoke of a “deutsche Weg”, or “German way”, as opposed to the “American way”. He adds that by the end of the 2000s, there was once again a triumphalist mood in Germany. “In particular,” he states, “there was an increasing scepticism about – and even contempt for – Anglo-Saxon ideas, whether about statecraft or about economics.” And this contempt can only have been increased by the refugee crisis, in which German and British attitudes have differed markedly. There may be many problems with Merkel’s open-door policy, but at least it demonstrated a generosity of heart that has been entirely absent from the British response. So, no, there is not going to be an Anglo-German partnership running the EU if we choose to remain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments