Singing in the rain: the philosophy of disappointment

You drop your favourite vase. The vase is not broken. It has been restored to its pre-vase state. So nothing is lost. West Ham crash out of the FA Cup. Trump is elected President... What is disappointment and how should we deal with it? Andy Martin considers, through its history and philosophy, how we can live with or overcome this difficult emotion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.True story. Involving a guy called Lucius, friend of a friend, and former professor of English. He had parked his car outside a convenience store in Princeton. As you do. And a stick-up happened to be taking place inside that same convenience store. As it will in Princeton, from time to time. And, almost predictably, the gunman comes running out and leaps into the back of Lucius’ car, holds a gun to his head, and screams, as is normal in these circumstances, “Drive or I’ll blow your fuckin’ brains out!”.

If it was me, I would be putting my foot down and driving away at top speed. Fast and furious. However, Lucius was no ordinary man. For one thing he was 90-something. For another he was, although just about fit enough to drive, afflicted with several painful and long-term ailments of the kind 90-year-olds are prone to. And thus spent half his time in and out of hospital, getting treatment, none of it pleasant. So, having briefly reflected on his options, he turns to the gunman and says, “Go on then, shoot me. You'll be doing me a favour.” The robber was so flummoxed by his composure that he ran off and was duly arrested.

The overriding feeling of both Lucius and his would-be passenger was one of disappointment in the performance of the other. Which I was reminded of recently when West Ham went down 5-0 in the FA Cup (against Manchester City). We can now, as they say, “concentrate on the league”. The great boast of West Ham fans is that they have far and away the saddest song in football: I’m forever blowing bubbles, true, but this is the crucial point, they only ever nearly reach the sky and then “like my dreams they fade and die”. And, as if to rub it in a bit more, “Fortune’s always hiding”. On the other hand, I’m not in favour of commissioning a more upbeat song.

I remember that back in the 1998 World Cup in France, when France, contrary to expectation, beat Brazil 3-0 in the final, the complaint of one rather literate Parisian in the pages of Le Monde was that the best the triumphant French fans could come up with was tooting their horns and leaning out of car windows, yelling, “On a gagné!” (We won). Relatively uninspired. I think he would have preferred the West Ham theme tune, more on the melancholy wavelength of a grand French tradition.

A château. A bedroom where your lover awaits. An illicit nocturnal rendezvous. The consummation of a romance. What more could you possibly ask for? Not a thing. All your desires have been fulfilled. Satisfaction achieved. The end. Except not if you are Julien Sorel, virgin and apprentice priest. Not if you are in a novel by the great 19th-century novelist Stendhal, as opposed to a Mills & Boon. He stumbles out of that bedroom “some hours later”, muttering a phrase that recurs in Stendhal’s writing generally with all the regularity of a mournful cathedral bell: “Is that all it is?” (“N’est-ce que ça?”) He has now officially had everything he ever wished for and he can’t understand what all the fuss is about. And it’s more than a passing post-coital mood. Julien swings around from an ardent romantic into an anti-romantic anti-hero. He suffers, in a word, like Lucius, the gun-toting robber, and like West Ham, the misfiring football team, from disappointment. He is disappointed even with fulfilment.

Stendhal, who trekked back from Moscow in the snow with Napoleon in 1812, leaving most of a 500,000-strong Grande Armée frozen in the Beresina or sliced up by Cossacks, knew all about bubbles fading and dying. But there is a further element to the art of life, the necessary complement to disappointment. It is there in the fate of Julien Sorel in the final pages of The Red and the Black, and it is echoed in the fate of Meursault at the end of Camus’ The Outsider, when he looks forward to the guillotine and fully expects to hear “cries of hatred” from the spectators. It is a combination that occurs, right now, in a more musical vein, in La La Land, where purist jazz counterpoints the dream factory. And it explains why, for example, the Rolling Stones’ album of blues songs has been so ironically successful. The blues = disappointment + stoicism.

I was recently reminded of one of the best examples of stoicism, beyond Sorel and Meursault and Ryan Gosling, when I was asked to consider writing a book about Ted Deerhurst, one of our great unsung British heroes. Ted (aka Viscount Edward George William Omar Coventry) was a surfer who yearned to become world champion. He represented Great Britain as an amateur and was inevitably drawn as a pro to Hawaii, the ultimate arena, the Coliseum of epic waves.

He may not have made it right to the top (I suppose he was the surfing equivalent of West Ham, destined for mid-table mediocrity), but he was the only surfer I knew who was capable of re-enacting a battle from the Second World War on the beach at Pipeline, using miniature toy soldiers and tanks, while waiting for his heat. He rode a board bearing the emblem of a sword and the word “Excalibur”, which was also the name of the charity he set up to enable under-privileged and disabled kids to go surfing. I remember his famous last words when, having registered in the end-of-year rankings at the Royal Hawaiian hotel at 235th in the world, he resolved to go and give snowboarding a whirl instead: “At least you can’t drown up a mountain.” Naturally he spent the next six months in hospital.

Ted supplemented his quest for the perfect wave with a concept of “the perfect woman”. It was probably because I had expressed some scepticism on the subject that he phoned me up from Hawaii in the middle of the night, transferring charges, to tell me that he had found her. And he eventually introduced me to Lola as well, at the club in downtown Honolulu where she worked as a pole-dancer. “She really does love me,” Ted assured me, stuffing a $20 note in her G-string. And he was only forced to cool off finally, and head for the mountains, when visited at his home by a couple of men in suits (a rarity in Hawaii) and armed with shotguns (not quite so rare). They were the henchmen of a drug baron who also claimed to be Lola’s boyfriend and wished to inquire how he would feel about surfing with only one leg.

In terms of surfing stoicism, I have to take my hat off to Bethany Hamilton, who surfed with only one arm, her right one, since a shark had chomped off the left one when she was only 13. I paddled out with her in Maui and she was still a way better surfer than I ever was with two arms. But my real education in Hawaii came from a woman in a café on Oahu who asked me where I came from. “You’re lucky,” she said. “How do you work that out?” I said, still intoxicated by giant waves and palm trees, few and far-between on the mean streets of the East End. “At least in England,” she replied, “nobody minds if you’re miserable.” She turned out to be a psychiatrist specialising in depression. “Ha!” I said, or something similar, finding it hard to credit her story.

So she actually took me to her clinic on the island and explained that just as many people are depressed in Hawaii as anywhere else on the planet but that because they were living in “paradise”, they felt guilty about it on top. And since they were technically living in America, if they were broke too, then they were thrice screwed. Contrary to Karl Marx, the point about psychiatry, she argued, was not to improve the world but only the way you interpret it.

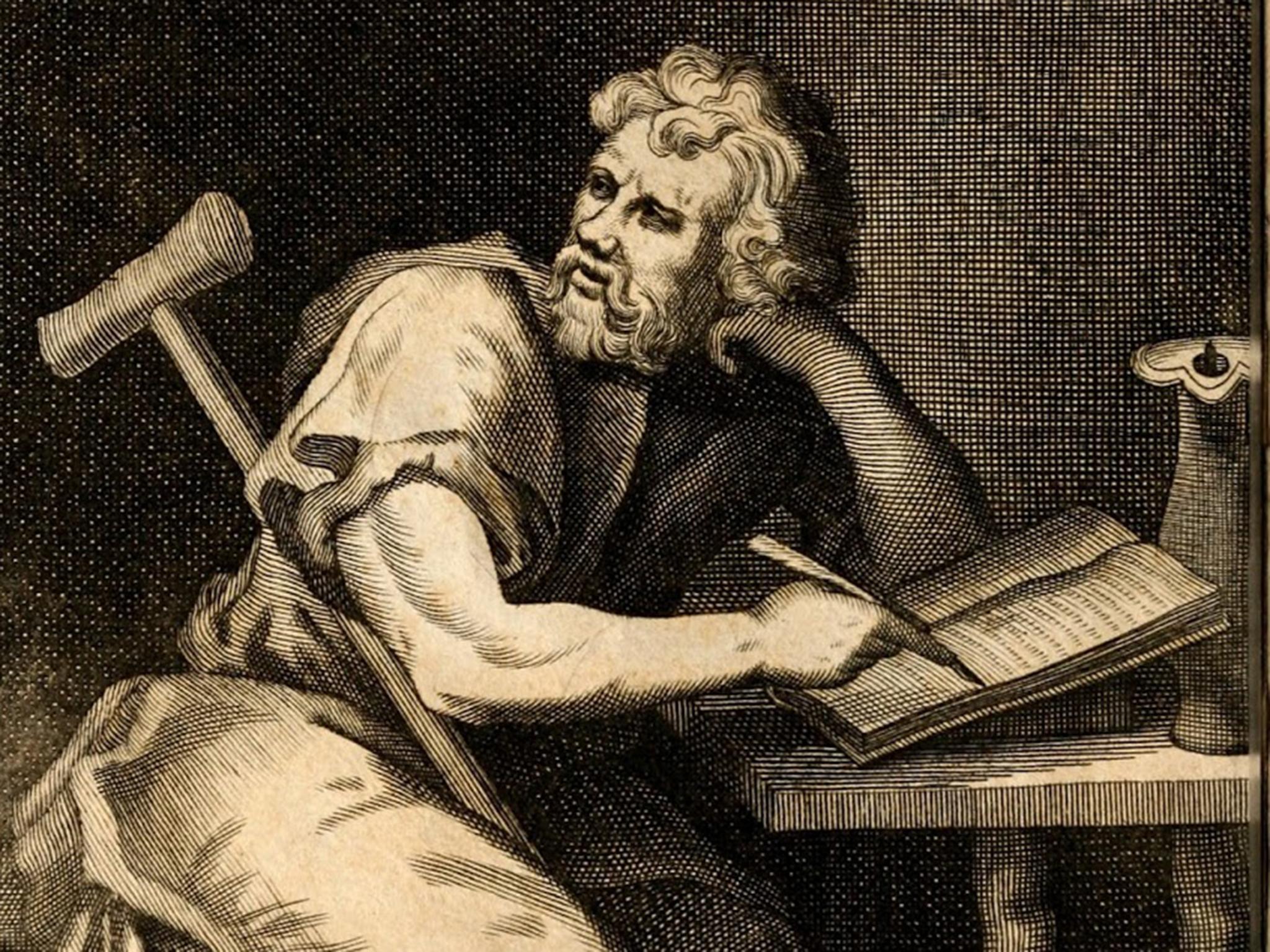

Which is where stoicism comes in. I believe it was founded, as a branch of philosophy, by Zeno of Citium (or Cyprus), but the best formulation that I know of is in the brilliant and provocative Enchiridion by Epictetus, who was crippled, and lived in the first century AD, in Rome and Greece. He recommends ways of coping with every kind of death and disaster you can imagine. But the more minor example of everyday disappointment that sticks in my mind is this one. Say your servant had just dropped your favourite vase (a classic Greek vase, decorated with Pan, a flute, and semi-naked nymphs) on to your stone floor and it has shattered into a thousand pieces. Do you crack up and give your servant a good kicking? Answer, no, says Epictetus. You say to yourself: “The vase is not broken, it has only been restored.” Returned, in other words, to its pre-vaselike state. So nothing has been lost. The vase itself was only a temporary anomaly. So too, all human life, condemned to entropy.

Stoicism is the ultimate expression of philosophical resignation and is completely admirable. But of course it contains its own contradiction since it expresses dissatisfaction with dissatisfaction. It is impossible to be stoical all the time. In the end you want to fix things and change the world, even if it’s only trying to stick that vase back together again or make a new one. Such is negentropy, a protest against the tendency of everything to fall apart.

In modern literary terms, the best case of the stoic who finally revolts is Jack Reacher. On a rooftop in Madrid, Lee Child, Reacher’s creator, says “philosophically, Reacher is a stoic. Stoicism is about all he has in the way of philosophy.” He can put up with unbelievable amounts of pain without moaning. He disdains paracetamol and aspirin. He can re-set his own broken nose and tape it up with duct-tape. But is he really a stoic?

Epictetus urges us to see no distinction between an “is” and an “ought”. Everything right now (no matter how bad) is just the way it ought to be. Nothing (tsunamis, volcanoes erupting, shipwrecks, Brexit, Trump or crashing out of the FA Cup) is that big of a deal, you say to yourself. Thus easing the pain and attaining the serene calm of ataraxia. Very cool. But hard to keep up.

Question: if the lone woman on the late-night metro in Paris is getting mugged or groped by some drunk, do you just sit there and lift up your copy of L’Equipe and concentrate on the day’s news? The Reacher response is an ascending scale, from indifference to a sense of injustice, to indignation and righteous fury. Sometimes a broken jug just cries out for fixing.

Lee Child puts down his fork and says: “Stoicism used to mean something like ‘Go with the flow’. It doesn’t sound much like Reacher, does it? He hates the flow.” Child had second thoughts: “Stoicism used to mean something like ‘Go with the flow’. It doesn’t sound much like Reacher, does it? He hates the flow.”

There are times when you have to stop being philosophical.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’ (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99). He teaches at Cambridge University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments