The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Sia’s film Music is anything but a ‘love letter’ to the autistic community. She should understand why

The singer-songwriter’s directorial debut could have been an opportunity to collaborate with autistic people, instead of speaking over them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.News that the central character in Sia’s directorial debut, Music, is autistic – yet is played by an actor who is not – catapults us back to the “cripping up” days of filmmaking.

Memorable movies that cast non-disabled people as disabled characters include 1988’s Rain Man, starring Dustin Hoffman as an autistic savant, and 1994’s Forrest Gump, with Tom Hanks as the slow-witted protagonist.

In 2020, 25 years since the Disability Discrimination Act and with disabled people bearing the brunt of Covid, Sia’s casting is a misstep and reflects how far the arts have to go in truthful depictions of disability.

The singer-songwriter has reacted angrily to accusations of ableism in casting Maddie Ziegler in the titular role of Music. She has explained the character has “special abilities”, that “casting someone at her level of functioning was cruel, not kind” and that there are 13 people “on the spectrum” in the movie which she spent three years researching. But there is no detail about what this research involved or the roles of the 13 people. And her fury at criticism from autistic or disabled people and their families jars with her description of the film as “both a love letter to caregivers and to the autism community”.

Based on the trailer, it is impossible to judge if the film can be called that at all. Its descriptions of the “magical” character and joyful shots of a smiley, open-mouthed ingénue lost in music do little to challenge narratives about autism or learning disability.

This was true of last year’s Peanut Butter Falcon. The film was a welcome, rare chance to see a learning-disabled actor, Zack Gottsagen, in a lead role. Yet it also reinforced triumph over tragedy and redemption narratives that often drive films about disability.

More recent examples of “cripping up” include the film Come as You Are, which admirably focused on disability and sexuality but did so through non-disabled actors playing disabled people. Then again, none of this is as shameful as last year’s play All in a Row, where the role of an autistic character was given to a wooden puppet.

Cian Binchy is an autistic performer whose highly-regarded one-man show The Misfit Analysis challenges assumptions about autism. Binchy, who was acting consultant on the National Theatre’s Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, says Sia’s film is “frustrating, but sadly not surprising”.

“I know what the film industry is like not taking disabled people seriously. There aren’t enough opportunities,” he said.

Binchy added that autistic people are often portrayed as not wanting the same opportunities as anyone else or as “people who don’t show much empathy or emotion or who fixate on one thing”.

“That is true for some, but not all autistic people. You can’t portray all of autism in one character because autism is a very, very complex condition.”

Patrick Collier, executive director of London-based inclusive theatre company Access All Areas, works alongside Cian and other learning disabled or autistic performers. “The nicest thing I can say about it is that it’s lazy,” he says of Sia’s film. “Sia is surely surrounded by a team of experienced producers, directors, and casting directors. How did none of them realise that this was a bad casting decision? They should know talented autistic actors.”

Just 6 per cent of people working in the UK arts scene are registered as disabled, according to Arts Council England, compared with 21 per cent of the general working population. Greater involvement of disabled people and their allies in production processes is vital, as Binchy and Collier say.

A lack of involvement and transparency is partly what is fuelling condemnation of the forthcoming Down’s syndrome abortion storyline in ITV soap Emmerdale. A petition demanding the story be scrapped has drawn almost 25,000 signatories, with huge questions over research and if families were involved.

We need more collaborative, authentic approaches like Binchy’s, or that of playwright Ben Weatherill, who wrote Jellyfish, starring Sarah Gordy who has Down’s syndrome. Or the biannual Oska Bright film festival that showcases work created by or featuring autistic and learning-disabled people.

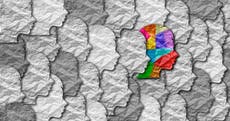

How disability is depicted in the arts can transform or reinforce attitudes, and it matters enormously to disabled people and their families. As Binchy says: “When disabled people see a film, they should be able to see a character they can identify with. When disabled people see a disabled character, we should see ourselves represented authentically.”

Saba Salman is the editor of “Made Possible: stories of success by people with learning disabilities – in their own words" published by Unbound

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments