Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What comes to mind when people consider Percy Bysshe Shelley? Too often it’s the blue eyes and fluffy hair of an effete toff poet, a sort of prototype Fotherington-Thomas who, when he wasn’t babbling about leaves and clouds, was pining for unattainable ladies; a man so ineffably wet that he managed to drown while messing about in a boat in Italy.

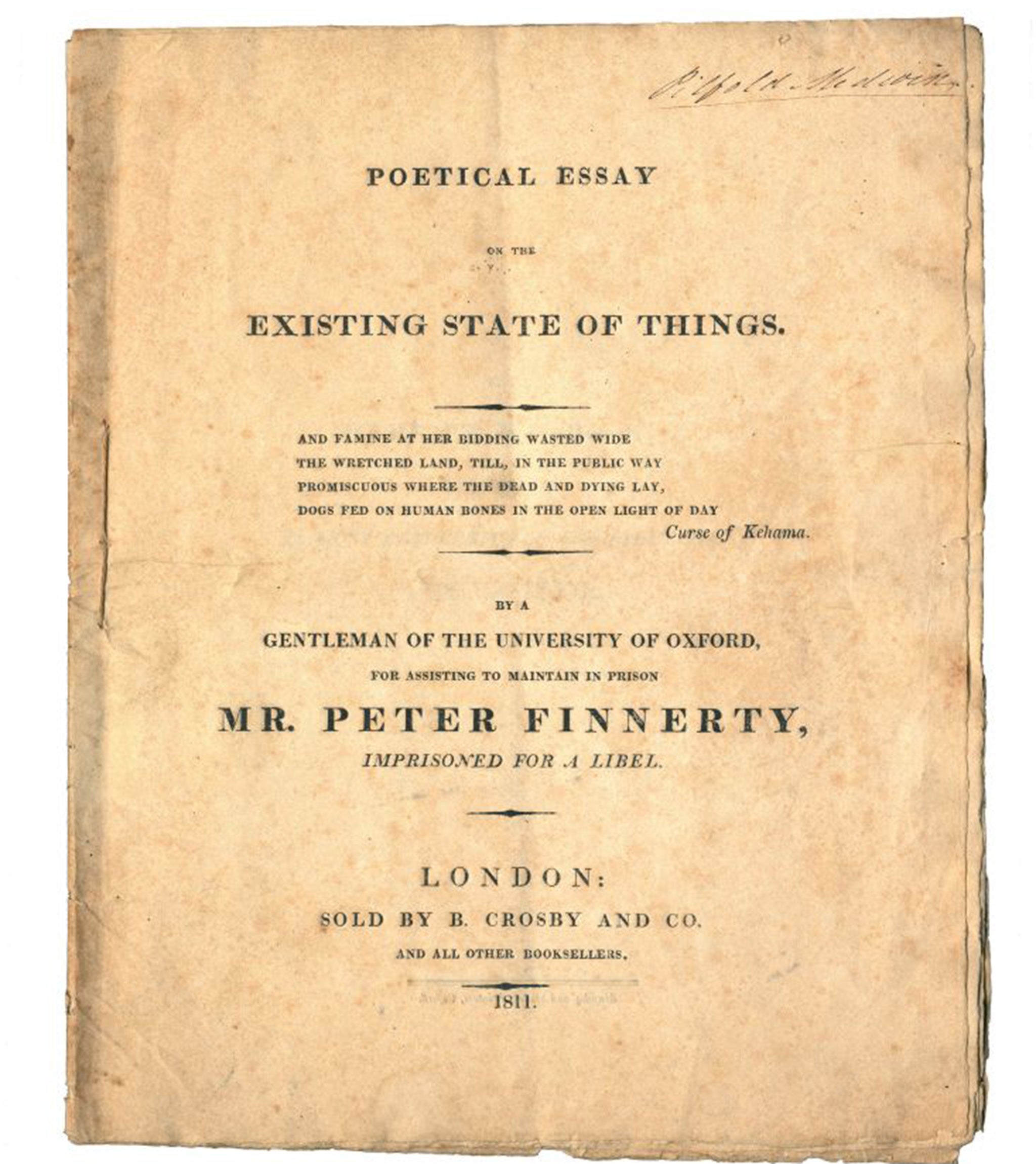

Which is why the publication of a long-lost political poem last week, “On the Existing State of Things”, is so rewarding for Shelleyan experts and fans. The open access would have thrilled the poet for a start. The more readers, the better; but this was poetry with a purpose, written out of rage and despair. His works fall into two broad categories: the more well-known literary pieces, addressed to a small group of cognoscenti; and the overtly political poems, powerful, plain and direct, aimed at a wider audience, including the downtrodden workers of his day.

The Victorians took the dead Shelley up as a supreme lyrical talent (he was that, too) and conveniently forgot the atheism and revolutionary tendencies. Most of the articles last week have used Victorian images of him, sugar-coated, rendered more seraphic to fit in with Matthew Arnold’s idea of Shelley as a “beautiful and ineffectual angel”. He was anything but.

Early 1811 was a particularly thrilling time for Shelley. Written under the alias “A Gentleman of the University of Oxford”, the poem came out before he was sent down in late March for publishing another incendiary pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism. He had come up to Oxford the autumn before, and quickly embarked on a bromance with a fellow undergraduate, Thomas Jefferson Hogg. With Hogg, Shelley pranked a variety of prominent people with spoof letters purporting to be from disillusioned vicars. Anyone tempted to reply was soon sucked into an increasingly wild, erudite but impertinent correspondence.

Added to the mix was the disappointment of his romance with a relative, Harriet Grove, who ditched her volatile cousin after two years. Intriguingly, the new poem is dedicated “To Harriet W–B–K”, clearly Harriet Westbrook, then a schoolgirl of 16, soon to become Shelley’s first (unhappy) wife.

The poem’s proceeds were devoted to the cause of the Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, who had been jailed that February for libelling (that is, criticising), the Tory politician Lord Castlereagh. Shelley was later to stain the Tory leader indelibly in “The Mask of Anarchy” with the brilliant couplet: “I met Murder on the way/He had a mask like Castlereagh”. The new poem is less assured, but no less scathing. In his great “Ode to the West Wind”, Shelley stated his aim: that his poems should be “the trumpet of a prophecy”, a call to action: “Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!” Two hundred years later, are we ready to listen?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments