People don’t report sexual assault out of ‘embarrassment’ – this needs to change

The revelation that so many victims feel ‘embarrassed’ points to a wider problem: namely that some victims may think they are responsible for their assaults, in some way

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

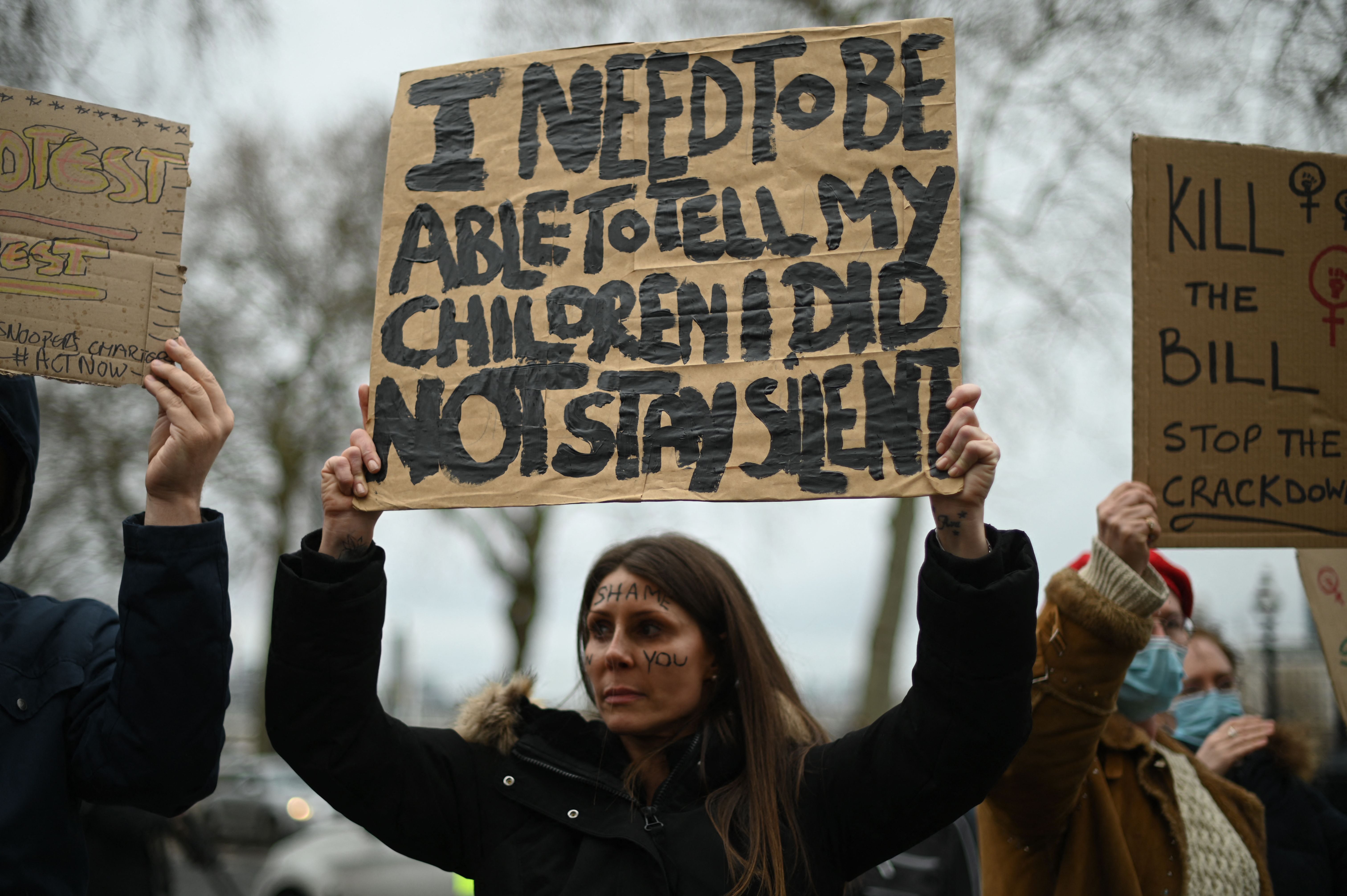

Your support makes all the difference.It took the death of Sarah Everard for the issue of female sexual assault to be raised to the national stage. Although we don’t have all the details of this crime, as due process has to be followed, we do have a timely insight into sexual offences provided by the Office for National Statistics.

From the off, the latest ONS report pulls no punches – it points to a mismatch between police recorded sexual offences, and the findings from its survey. While police records show 162,936 offences, the ONS survey found 773,000 people had experienced sexual assault.

This stark difference is endorsed by the finding that only 16 per cent of victims report the offence to the police – and, alarmingly, the most cited reason for not reporting a sexual offence is embarrassment (40 percent) closely followed by the fear that the police can’t help (38 per cent).

Despite recent reassurances from senior police figures and politicians – who have pledged to treat misogyny as a hate crime, and to place plain-clothed officers in nightclubs in a bid to increase safety for women – there is clearly a lot of work needed to win over the trust of victims, who are overwhelmingly female.

But the revelation that so many victims feel “embarrassed”points to a wider problem: namely that some victims still think they are responsible for their assaults, in some way. This has to be one of the few crimes where – as a society – we have endorsed and nurtured the twisted belief that it is victims, and not perpetrators, that are culpable.

Read more:

Adding to the urgent need for change is the revelation that almost half (49 per cent) of victims had experienced more than one sexual assault – and more than a fifth of these women had experienced three or more of these types of crimes.

Most victims reported being assaulted by someone of a similar age to themselves – two thirds of perpetrators are aged between 16 and 39. All of which not only highlights repeated offences, but repeated system failures in suppressing these experiences; let alone investigating them and providing justice.

The research shows that the most common location for sexual assault is the home (38 per cent), compared to public places – which account for only 9 per cent of crimes. This would suggest that placing a focus on providing better street lighting – and putting plainclothed police officers in bars –seems, at best, odd. At worst, it is tantamount to ignoring the most likely venue for these crimes: the victim’s home.

Dispelling another persistent myth that tells women they need to look after themselves and not drink too much to stay safe; the data pointsto the perpetrators – who are more likely (39 per cent) to be under the influence of alcohol or other drugs.

In the wake of Sarah Everard’s death, Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick sought to reassure women that abduction is “extremely rare”.

While this may be true, the ONS report found that more than one in 20 women had experienced rape – including attempted rape – since the age of 16.

This makes serious sexual assault far from a niche activity. And, while it is understandable that the police and politicians want to reassure women, those in power must accept just how common these types of crimes are – else change is unlikely to happen. After all, why would we prioritise something that is seen as “rare”, when there are so many more frequent threats to people’s lives?

We also need to face up to another unpalatable truth: that attention around the tragic death of Sarah Everard will eventually evaporate, just as it did with other terrible losses of life – such as the death of George Floyd.

But we have an opportunity, right now – while it is still being discussed – to use this new evidence to shape the way these crimes can, and must be, eliminated. Anything less ambitious is yet another failure to women.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments