Boris Johnson is wrong – as mayor of London, this is what I’m doing to tackle knife crime

It’s no coincidence that violent crime has steadily risen nationally within a few years of the 2010 election when investment reduced. Cuts really do have consequences

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Violent crime is continuing to rise across England and Wales. Every death on our streets is another life needlessly destroyed and another family left heartbroken.

To tackle this, good, tough policing is crucial. Those breaking the law must be caught, punished and reformed. But violent crime won’t be solved by the police alone. As well as focusing on enforcement, I’m determined to learn from what has worked, both here and abroad, in preventing serious youth violence from happening in the first place.

Many seem to have forgotten the mantra “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime”. Put into action, it drove more than a decade of falling crime under the last Labour government. Investment worked – in our police, as well as in communities and youth services to prevent crimes occurring in the first place. It’s no coincidence that violent crime has steadily risen nationally within a few years of the 2010 election when investment reduced. Cuts really do have consequences.

As the Home Office’s own evidence shows, cuts to policing budgets matter. Police officer salaries need to be paid for. For the first time since 2003, police numbers in London are below 30,000. That’s why it is ridiculous that my predecessor, Boris Johnson, is totally failing to acknowledge the role of his government in slashing funding to our police, compounding the problems caused by their huge cuts to preventative services and reduction in stop and search.

Despite my best efforts, within the rules and constraints set by the government, it is simply impossible to make up the £1bn in savings the Met have been forced to make since 2010. The £140m we have invested from City Hall in the last two years dwarfs the amount the previous mayor was willing to give the Met, but it’s still a fraction of what’s needed.

Similarly, slashing money for local councils, education, health and youth services has left London exposed to a rise in violent crime. I know how frustrated local councils feel, desperate to do more to support their local communities blighted by crime but can’t because they are so starved of funds.

Again, I’m not prepared to sit by and do nothing. We’re investing £45m in a brand new Young Londoners Fund – for projects to divert young people away from criminality. This is what the government should be doing, but aren’t, and I am trying to fill the huge void they have left.

My deputy mayor for policing, Sophie Linden, and the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick, have visited Scotland to continue to learn about the much-discussed public health approach they have deployed in Glasgow. I have met the team in London. Over a decade, this saw a massive decline in violent crime.

The public health approach deals with violence like you would with any other health issue that causes disease or physical harm – first, you contain it to stop it spreading, and then you tackle the causes to reduce the chances of it happening in the first place.

In some of the great leaps forward throughout medical history, we learned how to tackle infectious diseases by containing their spread, and by also stopping them breaking out in the first place through investing in improved public education, sanitation, housing and health.

In tackling violent crime, this means intervening at crucial moments in a young person’s life – ensuring those excluded from school, who suffer family breakdown, who experience trauma or who are victims of violence themselves, always have the right support from the relevant arm of government at the right time. We know that these factors lead to a higher likelihood of committing violence in later life so, by addressing them in young people, it’s possible to cut incidents of violent crime in the future.

I have already incorporated elements of a public health approach in my Knife Crime Strategy. For example, many of London’s major trauma centres are sharing information about violence not reported to the police. I’m also working with Ofsted and local councils and regularly bringing together the relevant agencies across our city, including NHS England, including through chairing the London Crime Reduction Board.

I’m confident we can make this work in London. But the most frustrating thing for me as mayor is that even though we know what’s required to get to grips with this problem, we simply don’t have enough funding or powers to deliver the solution in full.

There are three main reasons why progress was made in Scotland. First, they had the funding they needed. Second, they stuck to a long-term strategy that took 10 years to work. And, third, the key agencies that matter were signed up and knew the role they had to play.

This last point is crucial. Every relevant organisation in Glasgow took tackling the root causes of youth violence seriously and they were all directly accountable to one administration. In London, the system remains fragmented. Too many public services look upwards to Whitehall, rather than downwards to the needs of London’s communities.

While setting the police’s strategic priorities falls under my remit as mayor, I don’t have power to direct other agencies. My success depends on their willingness to cooperate. Londoners deserve a city where all agencies are accountable to its citizens and pull in the same direction. That is how, in the long run, we will solve this problem.

The government needs to place a legal duty on public bodies to spot the warning signs of violence and act upon them. Violence is not dissimilar from safeguarding duties placed on agencies. Overnight, this would raise the importance given to this issue and improve my ability to coordinate a London-wide approach to violent crime.

It’s important to remember that a public health approach is not an alternative to tough policing, but in addition to it. Glasgow showed how the police played a crucial role in their early successes in reducing violent crime – the containment part of the strategy.

My commitment to reducing violent crime is why I’ll never stop putting pressure on the government to provide the necessary funding to our police service and to the deliver a modern, innovative public health approach to tackling violent crime. However, when such a serious issue is affecting Londoners, we can’t just wait for this slow and apparently apathetic government to take action. I am implementing what I can in London right now, in those areas where I have powers and funding.

But we do need leadership from the top – an absent home secretary and a prime minister distracted by Brexit need to wake up to what is happening across our country. I’m furious that it is the communities like the one where I grew up in London – the very poorest communities – that are suffering the worst effects of this rise in violent crime. These communities, my communities, our communities, have been let down for far too long and it simply cannot continue.

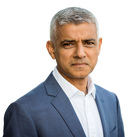

Sadiq Khan is the mayor of London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments