When my American friends ask why Russians don’t rise up against Putin, this is what I say

I come from the Soviet Union, from both Odessa and St Petersburg — meaning that I’m Ukrainian and Russian, both and neither. But I understand the mindset better than most

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When the war broke out I stopped sleeping through the night. I have to bear witness to every devastating detail. This war is in the land I am from. I watch the buildings being bombed. I watch the people, terrorized, forced to flee by the millions, seeking safety, leaving behind homes and photographs, husbands and sisters.

Some of my friends here in America are confused. I thought you were Russian, they say. You’re Ukrainian now? But it’s not that simple. Maybe I’m both — but I’m not sure I’m either.

I’m from the Soviet Union. And in our Soviet passports, before we turned them in when I was nine years old and were granted our refugee status, where my friends’ nationality said “Russian,” mine had said “Jewish.” After living under pervasive antisemitism, my family made the decision to emigrate to the US — and my beloved elementary school teacher moved me to the back of the class when she learned of my family’s upcoming betrayal of the motherland. She began calling me by last name only.

Go back to Russia, some kids said when I started fifth grade as a newcomer in the United States. But no, no, we are not Russian, I tried to explain in the few English words I knew. We are Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union. But I couldn’t say it and, anyway, it was too hard to explain. I focused instead on teaching them how to pronounce my name correctly, so it didn’t sound like broken sticks. No, not Yulla, not Ulla. Юля. Ю-ля… ля… Not Yulia either, not really. Those sounds don’t exist in English, so eventually I settled on the American version: Julia.

When the Soviet Union collapsed two years later, I became even more confused about my identity. We were from Leningrad, but now it was St Petersburg. And though I lived in Leningrad, I was born in Odessa, which was now in a different country: Ukraine.

Odessa holds the happiest memories of my childhood. Every summer, my family made our way, by a 36-hour train ride, boiled eggs packed for the journey ahead, down to our dacha, a little house my grandfather built himself. The train rolled through village after village with every platform packed with ladies in headscarves pushing homemade pirozhki through the open train windows. Very warm, they called. Fresh apples…pickled tomatoes. We chugged along through Russia and through Ukraine; it was all the Soviet Union. At every platform there were delicious smells and I pleaded to taste what they were selling. In one of those villages, we bought fragrant plums. In another, we bought salty sunflower seeds in little newspaper cones and cracked them with our teeth.

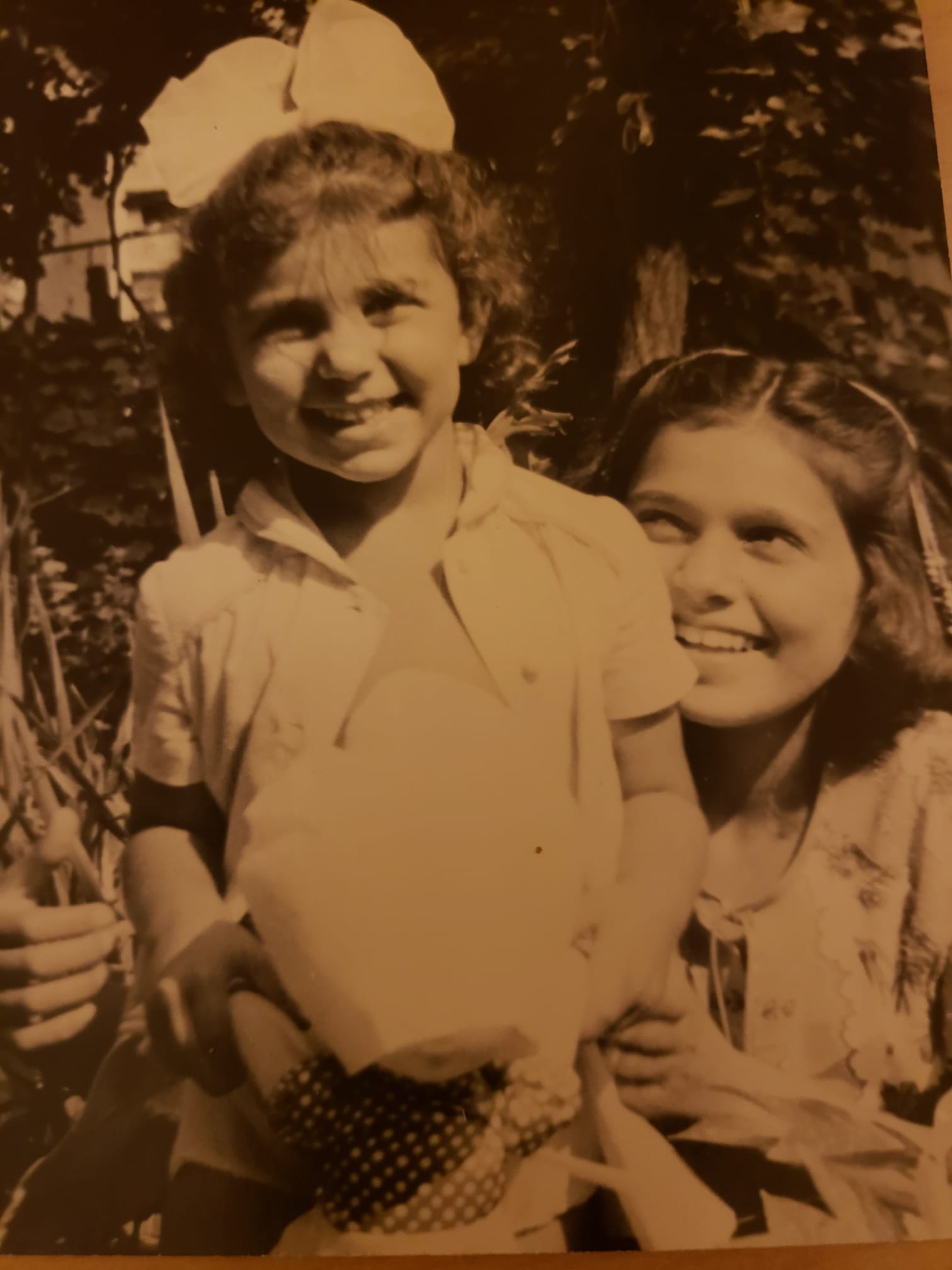

In Odessa — where my mom and aunt grew up, where my sister and I were born — in this place that was paradise to me, on our veranda surrounded by grapes, I listened to my grandparents tell countless stories of the Second World War. The war broke out on their prom night. (They had been together since the fifth grade.) They got married during the war. They told of trains, of far-away relatives, of hunger, hunger, hunger. Letters and fear and uncertainty and love and perseverance. My grandfather’s two brothers, who died in battle. This city held so much pain, so much heartbreak. But for me, as I sat on the roof and gathered sour cherries from our tree for the vareniki we would make together later — popping a few, warm from the sun, into my mouth, right there on that hot little roof — and as I frolicked in the salty water of the Black Sea, this city was pure happiness.

I see that beach on the news now. It is full of Czech hedgehogs, meant to block tanks; it is full of deep trenches and sandbags. The sandbags are piled in front of the opera house, like my grandparents used to describe during the war they lived through.

Every night I wake at two or three in the morning and check if our friend in Kyiv has done her “morning rounds” on social media. Is she alive? What buildings are destroyed? How many new civilian deaths? The collective anguish of my ancestors and every refugee pulses through me.

Now my American friends are asking: Why don’t the Russians stand up against this war? There are so many people there, surely everyone can’t be arrested. I try to explain about decades upon decades of systemic repression of rights. I try to compare it to systemic racism: it’s hard to change a whole system of thinking, centuries of expected behaviors. I talk about our own fragile democracy here in America. We saw that our institutions are not as strong as we hoped. All the safeguards we thought would stand strong were swept out of the way like houses of straw and sticks by the previous administration. The people who supported the insurrection, the attack on our own Capitol, still hold positions of power. I talk about the power of propaganda, controlled messaging, lack of access, disinformation. Look what Russia accomplished here, in our own country, look how they got people to believe such lies, look how they got so many to question election results, look how they divided us — and that’s here in America. The Russians are victims of their own country, too, but of course the suffering doesn’t compare.

I don’t know a single person here in St. Petersburg who supports this war, my friend from third grade tells me in a private message. And I get nervous that she uses the word “war” in case the government sees it. And I don’t ask her if she’s protesting. A bomb killed my friend’s mom in Kharkiv. What you are seeing there isn’t true, I tell her. They’ll never tell us the truth, she replies, but we know to believe nothing. She needs daily medicine but she says she now can’t get it because of American sanctions. So many of my friends are losing their jobs, she adds. The shelves are looking empty and I can’t find sugar.

“We made a terrible mistake not leaving when you did, not following you out,” my mom’s friend in Volgograd says to her on the phone. “I’m scared,” my other friend writes me. I don’t feel sorry for the Russian people, but I do.

During my childhood, I did not know when I crossed the line between Russia and Ukraine. One place was cold, one was hot. One had school and tennis lessons, one had fruit trees and the sea and joy. A long train ride, cold drumsticks wrapped in foil, sleep. I went back and forth.

Now the lines are clear. There is no confusion about who is the aggressor and whose lives are being destroyed. My heart and soul are with Ukraine. I’m still confused if I’m Ukrainian or Russian — both or neither? — but I know that the pain of it all is cumulative.

Some identifying details in this article have been changed to protect the families of those involved