An American correspondent visited Russia and Ukraine in 1929. He had some surprising insights

My great-uncle’s illustrated news dispatches from post-revolutionary Russia and Ukraine for the Cincinnati Post taught me a lot about how the US interacted with the rest of the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a 2020 off-camera interview with NPR anchor Mary Louise Kelly, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asked, “Do you think Americans care about Ukraine?” That question echoes today as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues, and peace talks make headlines.

So, do Americans care about Ukraine? In the summer of 1929, they did.“Follow Rosenberg Thru Russia,” written by my great-uncle Manuel Rosenberg, was a hugely popular daily series for the Cincinnati Post. Running from June through October as the most highly promoted news event of the season, the series promised “the greatest illustrated journey ever published.” One of the highlights of his trip, followed by thousands of the midwest city’s readers, was his visit to Kyiv, in Ukraine, where his mother, Celia Jasin Rosenberg, emigrated from in 1890. An excerpt reads:

For a city of 5000,000 Kiev is not inviting. Almost every house needs paint and repairs. Kiev has been the object of countless wars and battles. Several times it has been burned. Between 1916 and 1920, more than 500 pogroms took place within its borders. Tartars, Cossacks, Lithuanians, Russians, Poles and others at one time or another have taken possession of the city. Like Cincinnati, Kiev is built on a river near which are the factories and tenements. The better element lies on the hilltops.

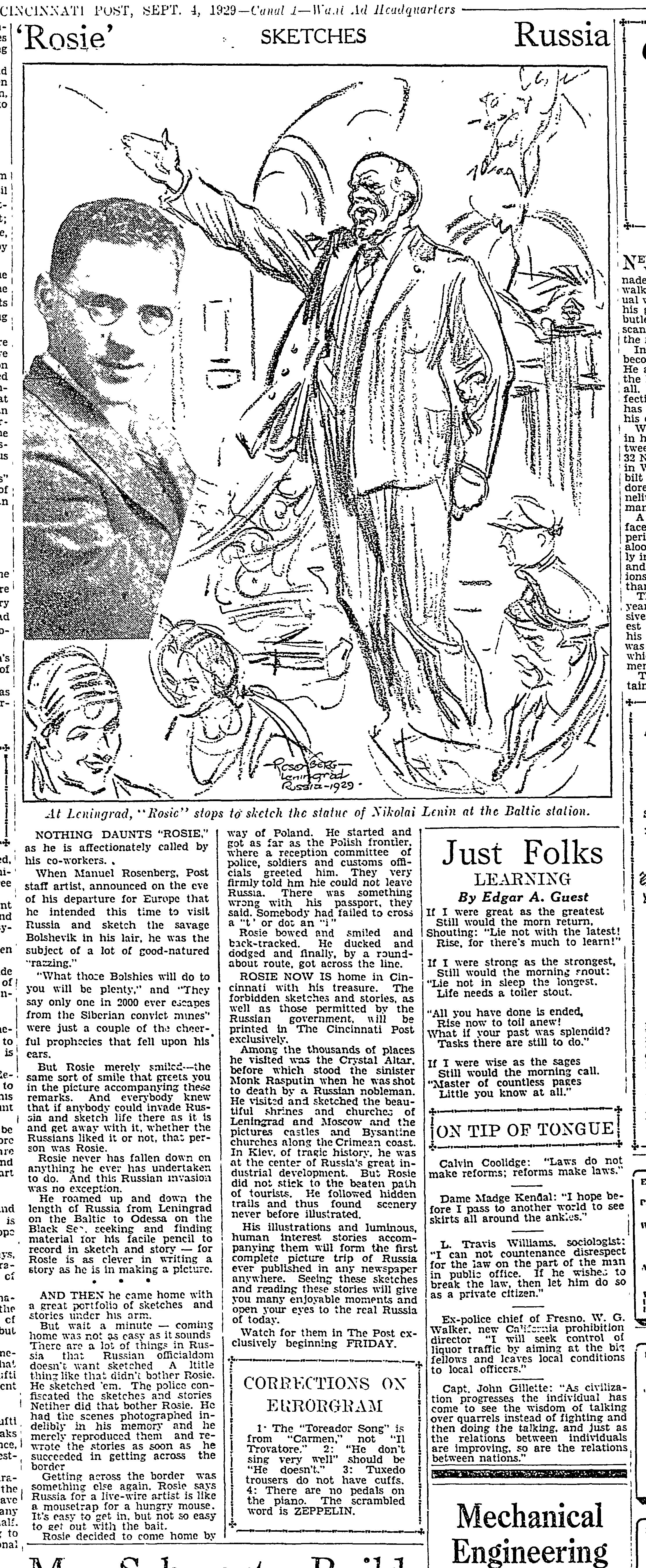

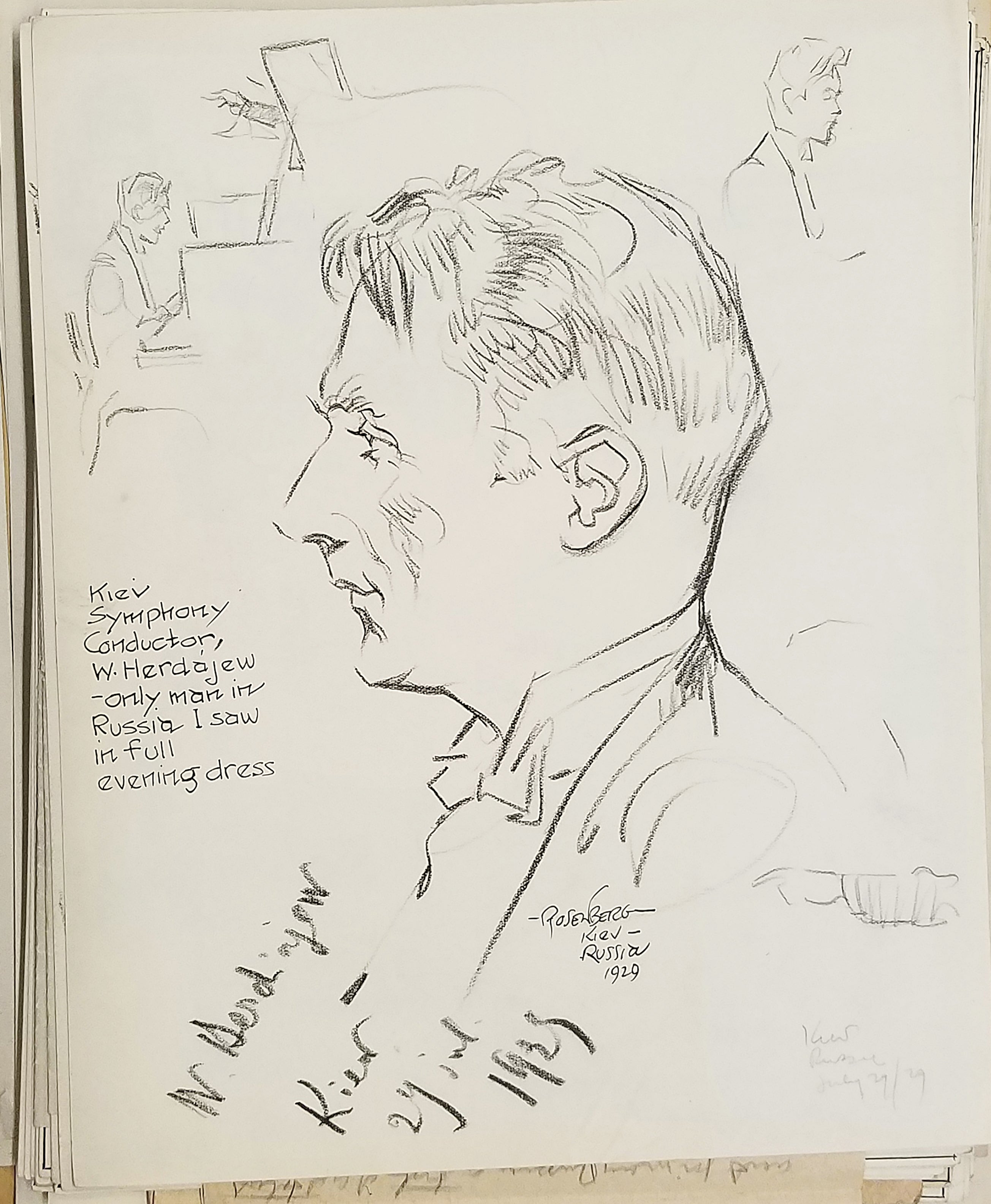

On staff as art director of the Cincinnati Post, the man known as “Rosie” was a talented writer as well as a skilled sketch artist, publishing in his syndicated column portraits of the famous and notorious from stage, screen, and radio to politicians, foreign dignitaries and crime-world figures. He’d started as a cub reporter at the same newspaper when he was 22. A syndicated Scripps-Howard newspaper founded in 1890, The Post enjoyed a reputation for editorial excellence and a daily circulation peak of 270,000-plus in 1960, before declining and eventually folding in 2007.

On September 4, 1929, a promotional piece in the Post described how Rosenberg intended to travel to the USSR:

NOTHING DAUNTS “ROSIE,” as he is affectionally called by his co-workers.

When Manuel Rosenberg, Post staff artist, announced on the eve of his departure for Europe that he intended this time to visit Russia and sketch the savage Bolshevik in his lair, he was the subject of a lot of good-natured “razzing.”

“What those Bolshies will do to you will be plenty,” and “They say only one in 2000 ever escapes from the Siberian convict mines” were just a couple of the cheerful prophecies that fell upon his ears.

But Rosie merely smiled --- the same sort of smile that greets you in the picture accompanying these remarks. And everybody knew that if anybody could invade Russia and sketch life there as it is and get away with it, whether the Russians liked it or not, that person was Rosie.

Rosie never has fallen down on anything he ever has undertaken to do. And this Russian invasion was no exception.

He roamed up and down the length of Russia from Leningrad on the Baltic to Odessa on the Black Sea seeking and finding material for his facile pencil to record in sketch and story – for Rosie is as clever in writing a story as he is in making a picture.

***

AND THEN he came home with a great portfolio of sketches and stories under his arm. But wait a minute – coming home was not as easy as it sounds. There are a lot of things in Russia that Russian officialdom doesn’t want sketched. A little thing like that didn’t bother Rosie. He sketched ‘em. The police confiscated the sketches and stories. Neither did that bother Rosie. He had the scenes photographed indelibly in his memory and he merely reproduced them and rewrote the stories as soon as he succeeded in getting across the border. Getting across the border was something else again.

Rosie says Russia for a live-wire artist is like a mousetrap for a hungry mouse. It’s easy to get in, but not so easy to get out with the bait. Rosie decided to come home by way of Poland. He started and got as far as the Polish frontier, where a reception committee of police, soldiers and customs officials greeted him. They very firmly told him he could not leave Russia. There was something wrong with his passport, they said. Somebody had failed to cross a “t” or dot an “i”. Rosie bowed and smiled and back-tracked. He ducked and dodged and finally, by a round-about route, got across the line.

ROSIE NOW IS home in Cincinnati with his treasure. The forbidden sketches and stories, as well as those permitted by the Russian government, will be printed in The Cincinnati Post exclusively.

Rosenberg’s fifteen-day steamer passage across the Atlantic from the port of New York took him to Europe on assignment by The Post to report on the romance and beauty of Europe. He started off in western Europe, traveling through Ireland, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Poland. To the east, the mysterious and closed-off Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, little more than a decade after the Bolshevik revolution and ruled by the newly ascendant Joseph Stalin, was a source of much fascination for American readers. Many were terrified by communism’s perceived threat to American capitalism and liberal society, while more than a few were intrigued by communism’s alluring promise of an egalitarian society.

It was also a time when, after a decade of prosperity in America, foreign travel had become relatively common for middle-class and wealthy people. When third-class steamship tickets were re-categorized as “tourist class,” sales increased from 278,331 in 1922 to 461,254 travelers by 1930. Rosenberg’s visit to the Old Country also held the attention of Jewish families in America with relatives left behind in Russia and Ukraine. Between 1891 and 1900, more than 593,700 Russian immigrants landed on American shores, growing to 1.6 million over the next decade. Fleeing poverty and antisemitic violence, they sought opportunity across the country and in the nation’s great cities.

Wherever he went, “Rosie’s” celebrity gained him entry to palaces, elite clubs, halls of government, Broadway backstages, the secret passageways of monasteries, and the inner sanctum of the Vatican.

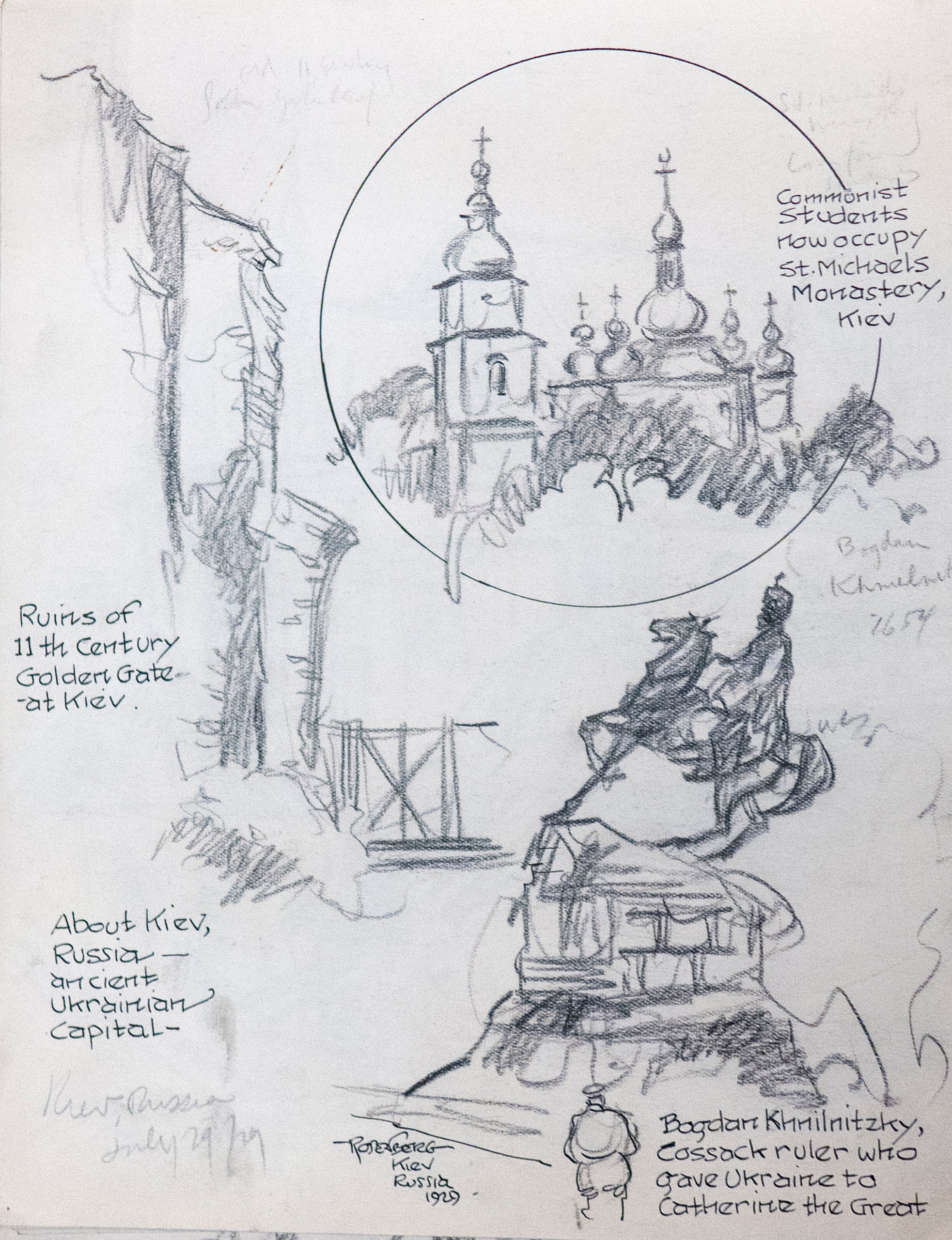

On October 2, 1929, Rosenberg’s dispatch as he entered Ukraine read:

BEGINNING OUR DEPARTURE from Russia, we entered at Sebastopol for a rough ride to Kiev, the ancient capital of the Ukraine.

Kiev was founded in the eighth century by three brothers, the first of whom bore the name of Kiev. Here in 988 Vladimir, the saint, gave the Greek Orthodox faith to Russia.

A huge statue of Vladimir, cross in hand, stands on the hillside of Kiev, overlooking the Dnieper River valley. In contract is the bust of Carl [sic] Marx, the German political economist, which stands on an odd arrangement of large black blocks, haphazardly set one on top of another…

As the cradle of Greek Orthodoxy, Kiev presents several fine examples of religious architecture. The most colorful is the Lavra, or monastery, in which are the catacombs.

The many oddly-shaped domes are a golden yellow and on the sides of the white limestone walls are painted icons in brilliant colors.

A priest takes us thru the catacombs, sandle [sic] in hand. We pass corpse after corpse with just a withered hand showing over the red drapery cover. Hermits lived in this labyrinth. They were sealed in their cells and thru small apertures were served food. When they died the openings were sealed with lead.

A month later, Rosenberg wrote of his departure from Ukraine:

WE LEFT KIEV one morning for a fast seven-hour run to the Polish border, en route to Warsaw. Numerous Americans had joined our party and we all hoped to crash thru the customs officers at the border. The Russian officials were most courteous. We could not have asked for better treatment.

It was getting very dark at 9 p.m. as we crossed the border. Two staves –the Russian striped deep red and black with its shield and coat of arms, a crossed sickle and hammer with a star above, and the Polish striped white and black with a white eagle as its crest design.

Presto, we were in Poland and the air itself seemed to breath of a greater freedom and a broader outlook. We even expected a good meal soon.

The train had not yet arrived at Zdobonova, the Polish customs station, when the passport office sang out my name. He could speak German and I soon learned there was a slight error in the Polish visa on my passport. He informed me I would have to go back to Kiev, seat of the nearest Polish consulate to obtain a proper visa.

***

HALF AN HOUR LATER all the passengers had entered the Polish customs office. I, too, picked up my baggage, saw my chance and slipped off the train. I had intended to escape to the main train and get to Warsaw where I likely could obtain aid from the American ambassador and have the visa corrected without having to spend two full days and about $60.

I made the mistake of walking into the commandant’s office. He demanded to know why I had dared to get off the train. He stepped out and soon returned with a guard armed with a rifle and two pistols.

Soon I discovered another chance to make a break for liberty. The military had brought in a woman suspect, whom the commandant was questioning. My guard also was interested. I picked up my baggage and tiptoed out toward the train.

I almost had reached the train when the commandant shouted. “Where are you going,” he demanded?

“I was just leaving my rips with my friends,” I said. But from then on he and the guard never left my side. As he marched me off to the waiting Russian train a loud protest came up from the crowd of Americans, but to no avail.

***

IN FIVE MINUTES the Russian train departed. The commandant and the soldier place me in a compartment with them and bid me sleep, but my dejection would not court sleep. At the border they said farewell and shortly the Russian customs head, commandant of the GYTU (Secret Service) for this station came aboard. He was a good fellow, full of sympathy, and roundly cured the Poles.

I wired the Polish consul and the next night arrived in Kiev and reached this house with a droshky (a low four-wheeled open carriage.) The next morning I journeyed back to the border.

On the return trip I met a Red army commander, who had been in a number of battles with Deniken, Petlura and other anti-Bolshevik commanders. I saw pictures of Jewish pogroms, in which more than 100,000 Jews had been massacred from 1918 to 1920 in the district in which we were traveling. An American lad had statistics which showed 1295 pogroms had been recorded here within those three years.

On arriving at Shepatouk I was well received –the border soldiery custom officers had learned of my misfortune and were quite friendly. I, alone, of all the travelers was permitted in and out of the customshouse, during the examinations.

On the Polish border I found equally friendly treatment. I learned later that the Warsaw correspondent of the Chicago Tribune, M.M. Nimowksy, had been reached by Mr. Wright, of our party. He immediately appealed to the minister of the interior who wired to Zdobonova that morning to let me thru without a passport visa. However, it was too late.

I called on Mr. Nimowsky at Warsaw the morning of my arrival. He received me royally and took me to the minister of the interior, the war minister. And a few other officials. The border commandant was “called upon the red carpet.”

“Rosie” survived this moment of peril on the Poland-Ukraine border, making his way back to Cincinnati where his popular travelogue published in the Post launched him on a lecture tour through the Midwest as an expert on European current affairs. As a child, I recall family gatherings where my paternal grandfather’s cultured, multi-lingual, well-dressed brother was regarded as “fancy.” Following his adventures abroad, he left journalism and started his own successful commercial publishing company, dying in 1967 at the age of seventy.

When I discovered his original illustrations in the collection of the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library and read his articles archived online, I felt admiration for Manuel Rosenberg’s courage. Venturing forth from America where prosperity and isolationism made the privileged majority feel safe — a country where his own Jewish refugee family found the opportunity to make a new life — he journeyed back to the troubled shtetl of poverty and pogroms. And why? Perhaps he understood, from his own history, the fragility of human existence everywhere, even in the Land of the Free, and I like to imagine that he felt compelled to deliver that message. As an artist myself, obsessed with how the past connects to the present, I’m grateful for my great-uncle Manuel’s reminder that yesterday’s newspaper is today’s Facebook post.