Forget Russell Brand – tech companies are to blame for the spread of conspiracy theories

Conspiracists like Russell Brand aren’t that different from others who desperately appeal to the anxieties of their audiences for clicks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the 24 hours after this column is published, it’s likely I’ll be accused of being a “shill” for mainstream media, a globalist, someone in receipt of funding from Big Pharma (looking at my energy bills, that be welcome), or an agent of Russia, China and/or NATO.

By this logic, my humble, 800-word column will be part of a co-ordinated effort – carefully planned by a mixture of powerful media tycoons, plotting politicians and major global institutions – to suppress and diminish the truth. Few will have likely read it or considered its argument. Instead, this article will become little more than a symbol – one that reinforces of a broader conspiracy – of an all encompassing, though unrecognisable and indescribable enemy. One that must be wiped out at all costs.

Perhaps I’ve given this column a little too much credit. But it is worth considering how the abundance of information online – articles, tweets, videos, podcasts and TikToks – can make understanding and interpreting information, particularly on issues such as war and economic catastrophe, an almost impossible task.

The constant production of content – often exaggerated and hyped up to go viral – ends up decontextualising important parts of the news to appeal directly to our emotions. It gives people a skewed perspective on global events and what their priorities should be. Moreover, this strategy of sharing information to meet traffic targets has a knock-on effect: leading people directly toward bizarre and sometimes harmful conspiracy theories. It has real world consequences.

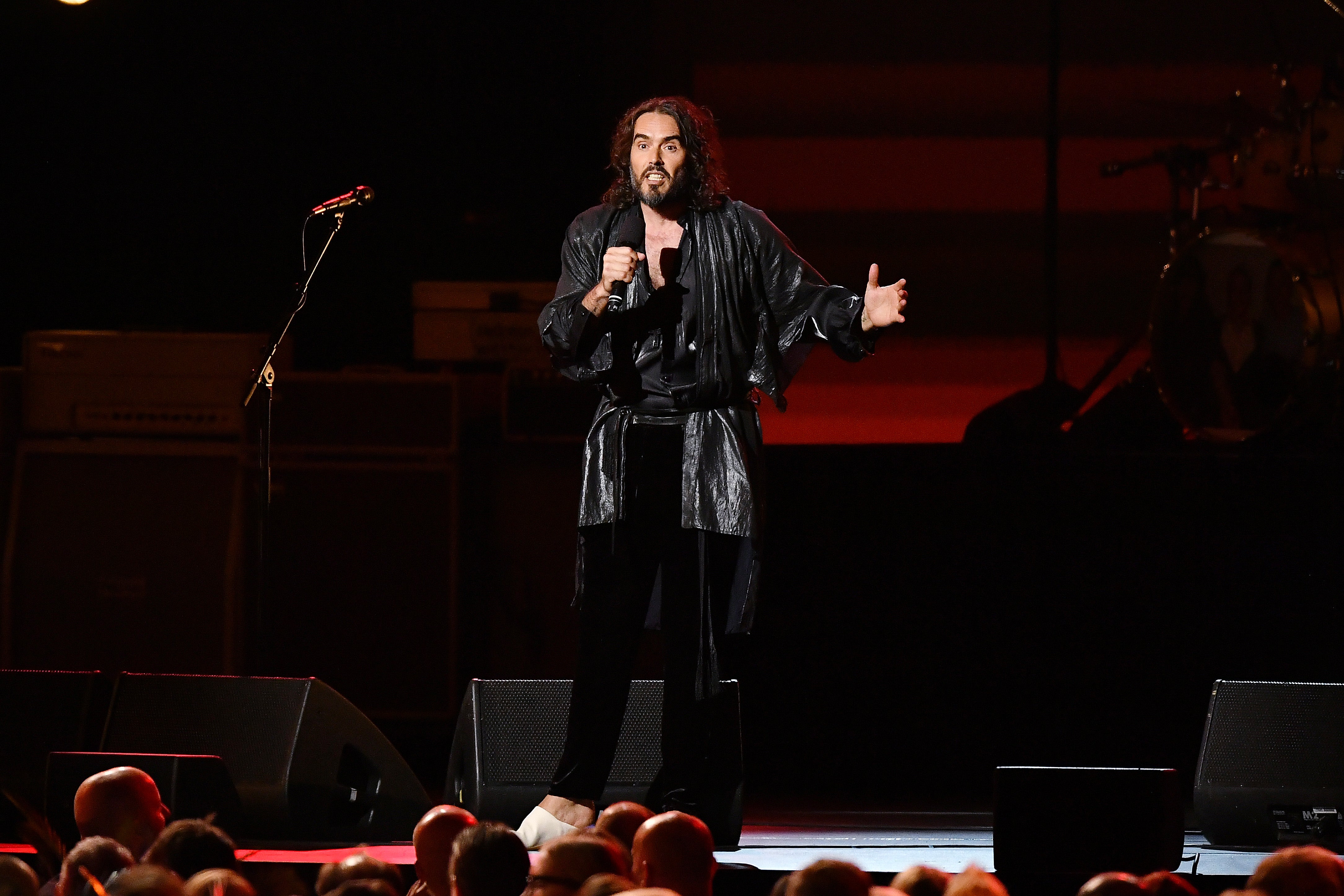

Recently, clips from Russell Brand’s Youtube channel, in which the comedian-actor-podcaster-wellness-enthusiast espouses familiar conspiracy theories around Russia and Ukraine (including those originating from Russian state propaganda directly), have circulated around social media.

Brand has become a popular figure for fringe conspiracy movements. He is regularly featured across anti-vax Telegram and Whatsapp channels, and enthusiastically shared by the QAnon movement (although Brand has not expressed any affinity or support for it).

To some, Brand’s seemingly sudden change to preaching extreme conspiracies has been surprising. For others, his transition from a mainstream comedy darling to a sentient comments section was inevitable, rather than implausible.

All this has raised concerns that spreading overt conspiracy theories to Brand’s 5 million strong fanbase may pose risks to public health, with severe consequences for both the current and future pandemics. Brand may be influential to a degree, but I would argue that focusing critique on him misses the wood for the trees. We fail to recognise that, for the most part, Brand’s conspiracies aren’t really all that new or novel. Nor are they revelatory enough to meaningfully challenge the institutions of power he believes are trying to silence him.

Indeed, having watched several of his YouTube videos over the past few months, it’s not difficult to find the same rhetoric – sometimes word for word – from obscure newsletters, message-boards and even established newspapers. What struck me the most wasn’t what he was saying or even what he believed was happening.

It was that, in most of his videos, Brand was simply recycling old, popular conspiracies I’d seen dozens of times on Flash Game forums and Anime message boards. Many of his videos show him simply reading out articles he’d printed, pausing at certain points in order to draw hasty observations, to arrive at a conclusion he’d already decided on.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

What Brand does isn’t that dissimilar from what other columnists and professional commentators you regularly see on talkRADIO, LBC or GB News do on a near daily basis. Moreover, his appeal has much to do with the current structure of the internet itself. In an increasingly sterile, sanitised and policed internet, where we often feel powerless to the algorithm, Brand does what nearly every successful piece of viral content does – from the “Ice Bucket Challenge” to Mr Beast’s Squid Game – invite the viewer to participate directly.

He incorporates a broader mission of exposing shadowy elites, but ultimately, Brand demands what every professional content creator does: to like, subscribe and share his #content. While conspiracy theories were earlier spread by spamming message boards and clogging email inboxes, now they are driven by hyper-personalised platforms.

In that way, sharing conspiracy theories isn’t just about supporting a creator – it becomes a virtuous act, tantamount to participating in a global movement.

But conspiracists like Brand really aren’t that different from most media outlets and news organisations who desperately need online engagement, and some of whom appeal to the anxieties of their audiences for it. Far from challenging the systems run by Silicon Valley elites, Brand’s success really comes down to understanding the tech platforms he is publishing on. And, more importantly, knowing exactly what tech companies really expect of him as a content creator.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments