Rupert Cornwell was born to be a foreign correspondent

Writing about Italy, he once said, was like eating 'too much chocolate cake'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

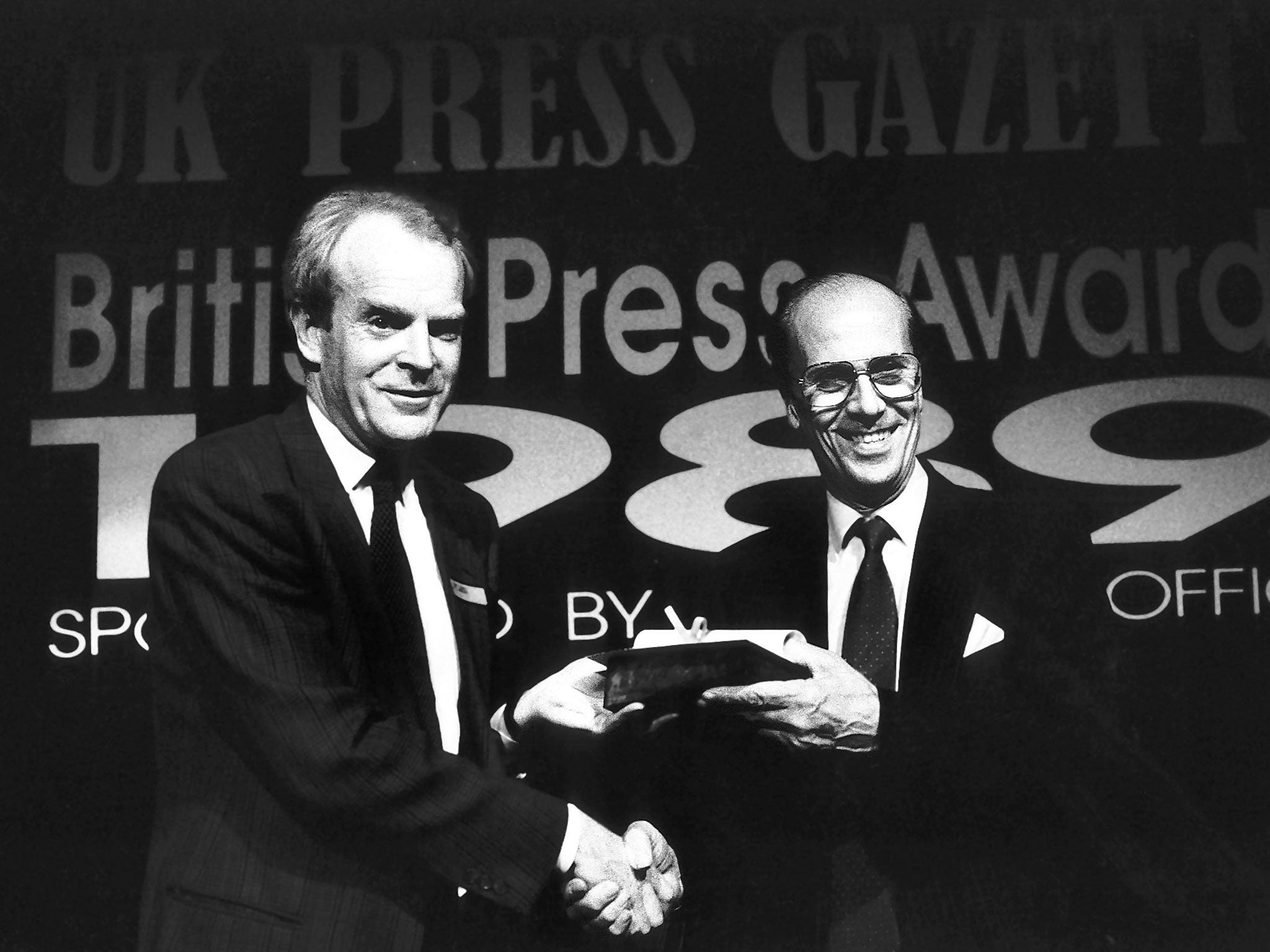

Your support makes all the difference.The first thing to know about Rupert Cornwell is that he could flat out write, the second that he was born to be a foreign correspondent. It was a marriage made in heaven, a love affair that endured for over 40 years.

Words, obviously, ran in the family. His father used them, allied to a certain charm, to con people. His older half-brother, David, goes by the name of John Le Carré and his sister, Charlotte, interprets them on the stage. Rupert, with his cool elegant style, wry humour and analytical mind, was to the Cornwell manor born.

The beauty of being a foreign correspondent – and his postings, for Reuters, the Financial Times and The Independent, numbered Paris, Rome, Bonn, Moscow and Washington, not to mention a stint in the most alien of places, Westminster – is that you get to write not just about the capital city but the whole country. That played to his strengths. So did his linguistic abilities; he learned to speak fluent Russian “on the run”.

An additional charm is the distance from head office, never his natural milieu. He liked to work things out for himself, without a thousand editorial voices jangling in his ears.

Robert Fox recalls their days in Rome when he was trying to work out the secret of his apparent nonchalance. James Buxton, then an FT colleague in the bureau, said “he slammed the door, made a maximum of three phone calls and out would come the perfect news feature” – regardless of whether he actually made any phone calls.

But the Italian job did bring him perhaps his greatest scoop – a detailed explanation of how Roberto Calvi (God’s Banker, in Rupert’s book, who had been founding hanging from under Blackfriars Bridge) laundered vast amounts of money in collusion with the Vatican Bank. That required, certainly, more than one phone call.

But he was not a noisy correspondent, forever shouting questions and generally demanding to be recognised, nor one to be seen covering wars in a flak jacket or military helmet.

He told Robert Fox: “You are attracted by danger, I run away from it”.

Conor O’Clery of the Irish Times, with whom he shared an office for five years in Moscow, recalls he rarely asked questions in press conferences. And his preferred garb was the well-tailored jacket and sweater. Oh, and a decent glass of wine, or vodka, or whatever the locals were drinking.

Of course he had great stories to cover, not merely Calvi but Perestroika in Russia and the rise of Barack Obama in America (he was just getting his teeth into Donald Trump when he died).

Writing about Italy, he once said, was like eating “too much chocolate cake,” but he was always drawn to Russia. He desperately wanted to go there for the FT but the job had been promised to somebody else. So he joined The Indy at its creation and was immediately sent there (perversely, the chosen FT man changed his mind and never went. I was FT Foreign Editor at the time and the memory still hurts).

Washington suited him, not least because his wife, Susan, had her own flourishing career covering Congress for Reuters. He could indulge his love of sports. He was long off the tee, if not always straight, at golf and became enamoured of baseball.

One of his most memorable pieces was a gorgeous pastiche, written as Damon Runyon would have, when the Boston Red Sox won the World Series in 2004, breaking the drought that had lasted since the team sold Babe Ruth in 1918.

However, his heart still lay with Arsenal, whose matches he would try and see whenever in London, with a brief detour to Charlton Athletic. Towards the end of his life he was delighted to find so much English football live on US television, but never if a better European match was on.

The goalless draw a few weeks back between Manchester City and Stoke held no attraction compared with the simultaneous and momentous Barcelona-PSG encounter.

But there was, still, a quintessential Englishness about Rupert; not quite of the stiff upper lip variety, though he was stoic about his final illness, but more a general diffidence that was almost a shyness.

He did not talk much about his family, apart from one lovely tale about his father stiffing the FT Paris bureau chief with the bill for an expensive dinner. In a way he was not easy to know but then he let his writing talk for him, which was enough for most of us.

Jurek Martin is a former foreign editor of the Financial Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments