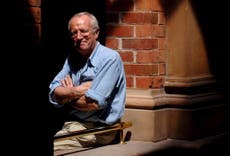

Robert Fisk wasn’t only a magnificent journalist, but a ‘historian of the present’ who illuminated the world

My friend did not invent the old journalistic saying ‘never believe anything until it is officially denied’ but he was highly sceptical of government sources, writes Patrick Cockburn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I first met Robert in Belfast in 1972 at the height of the Troubles when he was the correspondent for The Times and I was writing a PhD on Irish history at Queen’s University.

I was also taking my first tentative steps as a journalist, while he was swiftly establishing a reputation as a meticulous and highly-informed reporter, one who responded sceptically – and rigorously investigated - the partisan claims of all parties, be they gunmen, army officers or government officials.

Our careers moved in parallel directions because we were interested in the same sort of stories. We both went to Beirut in the mid-1970s to write about the Lebanese Civil War and the Israeli invasions. We often reported the same grim events, such as the Sabra and Shatila massacre of Palestinians by Israeli-backed Christian militiamen in 1982, but we did not usually travel together because, aside from the fact that Robert usually liked to work alone, we wrote for competing newspapers.

When we did travel together during the wars, I was always impressed by Robert’s willingness to take risks, but to do so without bravado, making sure we had the right driver and the car had petrol that had not been watered down. One reason he had so many journalistic scoops - such as finding out about the massacre of 20,000 people in Hama by Hafez al-Assad in Syria in 1982 - was that he was an untiring traveller. One friend recalls that: “He was the only person I’ll ever know who could, almost effortlessly, make up limericks about the south Lebanese villages, while he was driving through them.”

Yet there was a deadly serious reason why he was visiting those villages. When I was a correspondent in Jerusalem in the 1990s, they were the repeated target for Israeli airstrikes, which the Israeli military would declare were solely directed at “terrorists” and, if there were any dead and wounded, they were invariably described as gunmen who deserved their fate. Almost nobody checked if this was true - except Robert, who would drive to these same shattered villages and report in graphic detail about the dead bodies of men, women and children, and interview the survivors.

Robert was suited to Beirut with its free and somewhat anarchic atmosphere, a place always on edge and with people - Lebanese, Palestinian, exiles of all sorts - who were born survivors, though sometimes the odds against them were too great. Robert had a natural sympathy for their sufferings and a rage against those who inflicted them. His sympathy was not confined to present-day victims: for decades he wrote about the Armenian genocide, carried out by the Ottoman Turks during the First World War. He would publicise diaries and documents about the mass slaughter of the Armenians, stories which other correspondents felt it could be better left to the historians.

But Robert was more than a journalist cataloguing present-day developments and woes. He was a historian as well as a reporter who wrote, among many other books, The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. I never finished my PhD in Belfast because the violence became too intense for academic work, but Robert did get his doctorate from Trinity college for his thesis on Irish neutrality in the Second World War. My point is that Robert was more than a person who covered “the news”, since his journalism – for all his scoops and revelations – had such depth because he was, in many respects, “a historian of the present”.

He was also, of course, a magnificent reporter who bubbled with nervous energy, often shifting his weight from one foot to the the other, notebook in his hand, as he questioned people and probed into what had really occurred. He took nothing for granted and was often openly contemptuous of those who did. He did not invent the old journalist saying “never believe anything until it is officially denied” but he was inclined to agree with its sceptical message. He was suspicious of journalists who cultivated diplomats and “official sources” that could not be named and whose veracity we are invited to take on trust.

Some have responded to his criticism with baffled resentment: during the US-led counter-invasion of Kuwait in 1991, one embedded American journalist complained that Robert was unfairly reporting on events, knowledge of which should have been confined to an officially sanctioned “pool” of correspondents. Another American journalist based in London in the early 1980s once said to me that Robert was a magnificent writer and reporter, but the American had been struck by the number of his colleagues who grimaced at Robert’s name. “I have thought about this,” he told me, “and I think that 80 per cent of the reason for this is pure envy on their part.”

We saw more of each other after we both joined The Independent, Robert in 1989 and myself in 1990, on the eve of the first Gulf War. I was mostly in Iraq during the fighting and Robert was in Kuwait. Twelve years later we met in Baghdad after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and drove out together over land across the desert to Jordan. I recall that we were stopped for a long time on the Jordanian side of the border because Robert had secured, from the wreckage of some police station, in Basra in southern Iraq, a file of laudatory poems written to Saddam’s ferocious police chief in the city by his underlings on the occasion of his birthday. Some of the Jordanian officials thought that these craven offerings were hilarious, but others found the documents mysterious and kept us waiting for hours at the bleak border post while they waited for official permission to let us cross.

As we grew older, we grew closer. We had similar doubts about the beneficial outcome of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011, having seen similar optimism about the invasion of Iraq in 2003 produce a paroxysm of violence. Neither of us believed that Bashar al-Assad and his regime was going to fall, at a time when this was conventional wisdom among politicians and in the media. To suggest anything to the contrary got one immediately targeted as a supporter of Assad. The sensible course was to ignore these diatribes and Robert and I used to counsel each other not to overreact and thereby give legs to some crudely mendacious tales.

Over the last 15 years we talked almost once a week about everything from the state of the world to the state of ourselves, supplementing phone calls with periodic emails. A life spent describing crises and wars made him more philosophical about the coronavirus pandemic than those with less direct experience of calamities. In one of the last emails I received from him, he wrote that “Covid-19, unless it suddenly turns into a tiger, will be seen as just another risk to human life – like car crashes, cancer, war, etc. Human’s don’t necessarily fight disease, injustice and sorrow. They just survive and bash on regardless.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments