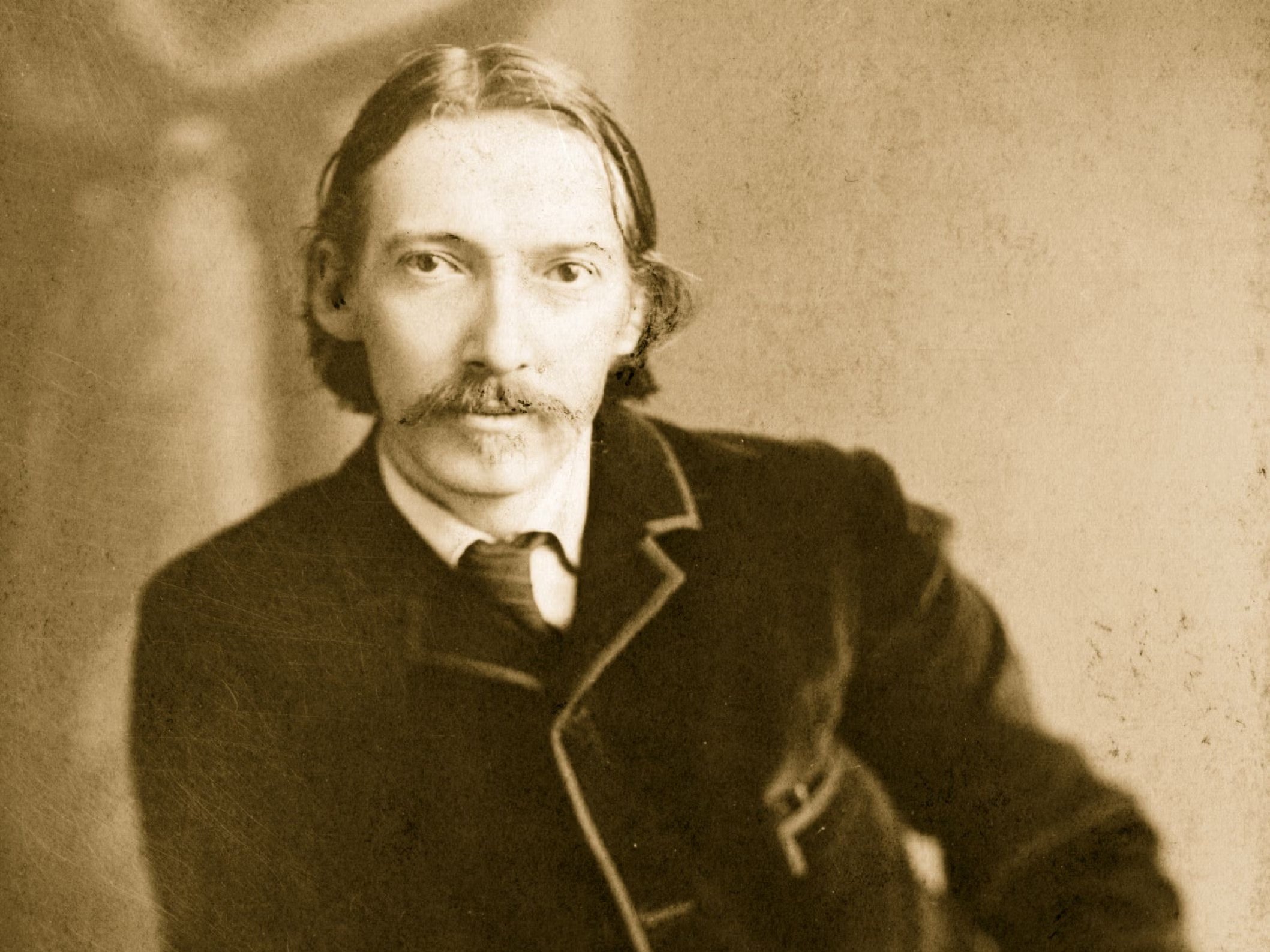

Yes, we should spend £800k of taxpayers’ money on ‘decolonising’ Robert Louis Stevenson

No surprise that the news we’re paying academics to expose colonial stereotypes in literary classics has wound up the anti-woke mob. But, argues Katie Edwards, it’s not as daft they think...

What’s the latest on crazy so-called “wokery”? Let me see… ah yes, it seems to be the news that the academic funding body UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) has awarded researchers at the University of Edinburgh £809,334 for a three-year project called “Remediating Stevenson: Decolonising Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pacific Fiction through Graphic Adaptation, Arts Education and Community Engagement.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly in the current febrile political climate – where even hot cross buns can cause a stir – this news has rankled in some quarters. The gist of the complaints seems to be that studying colonialism in some of the most influential literary works of all time, by one of the world’s most famous authors, is a waste of money.

Well, I suppose whether or not it’s “wokery” or an important issue for academic investigation depends on whether you care about lives being negatively affected by said colonial literary tropes.

And frankly, my friends, anyone thinking colonialism is a relic of the past is deluded. The effects of colonialism are still with us, from racism and xenophobia to nations’ wealth and resources. A 2023 UN report on the “negative impact of the legacies of colonialism” said “the weight of colonialism was still being carried today, most prominently in the global South.”

But colonialism has infected almost every country in the world – and its effects are still being felt today. From economic inequality, environmental degradation, over-incarceration, dispossession of land, and the erasure of languages and cultures.

So, for a load of white English people to dismiss the work of decolonising the university curriculum and deride the critical study of literature is at best parochial and at worst a perpetuation of the very legacy the Edinburgh project seeks to critique.

As Nada Al-Nashif, the UN deputy high commissioner for human rights, says “No state has comprehensively accounted for the past or the ongoing consequences.” And that’s true. But anyway, let’s all become pearl clutchers about some hard-won research funding, eh?

After all, how much is too much to change a cultural legacy of colonialism? According to some detractors, it’s not worth anything at all. But, having worked as an academic, I can tell you that money isn’t given out for nothing. Getting money for Arts and Humanities research is a squeeze at the best of times. Resources are scant and the competition is fierce. And applying for research funding is very much a competition. And don’t be under any misapprehension that daft academics are gadding about the globe on the taxpayers’ buck. They’re not.

Quite rightly, the funding application process is long, detailed and comprehensive. To finally get to a stage where they’ve been awarded the cash, the project team will have spent many days and nights sweating over the application, drafting and redrafting the various bits and wondering why, given the astonishingly low success rates of Arts and Humanities funding applications, they’re even bothering. I know, because I’ve done it.

The Edinburgh project will have gone through many stages of evaluation. The entire process takes months, sometimes years. First, the application will have gone through the university’s internal review process before submission to the funding body. Once submitted, it will then have been subjected to various stages of anonymous external peer review. Part of that review will have been a keen focus on value for money.

The UKRI website tells us that the project will produce “the first ever graphic adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s three Island Nights’ Entertainments stories, translated into Samoan and Hawaiian. Other outputs include new poetry by indigenous authors; a documentary film; an exhibition and a website.”

For the application, the project team will have submitted a detailed budget with costings, outlining exactly how the funds will be spent on these activities if awarded, along with a clear rationale for why the money’s needed. Of course, the project lead is held accountable for how the budget’s managed during the award period. Monies unspent are returned to the UKRI.

Let’s get this clear: the UKRI don’t fund jaunts for academics itching to get out of their ivory towers. They fund credible, robust peer-reviewed academic research.

Surely, the issue of outdated stereotypes is sufficiently serious to warrant investigation, especially in texts by an author whose work is studied for GCSE English and widely taught to Key Stage 2 children in primary schools.

I mean, what do “The Outraged” want? For cultural texts to be set in aspic? For them never to be subjected to scrutiny? Why should some authors and their work be beyond criticism? They shouldn’t. But, given the scandalised responses to edits to the work of Dahl, Austen, Agatha Christie and a host of other authors, you’d think Edinburgh’s approach would be met with a sigh of relief. There’s no suggestion of editing the text. There’s no mention of erasing terms or censoring passages – only the investigation of the work’s impacts and influence in the contexts of where it was written and set.

For those lamenting that the research is undermining the value of Stevenson’s work, the project acknowledges that he was “actively involved in supporting Samoan and Hawaiian indigenous sovereignty movements at a crucial period just before these islands were annexed by the US and Germany”, and that his Pacific fiction is “iconoclastic in featuring indigenous protagonists with considerable agency and dignity, and offering a critical proto-modernist perspective on western imperialism”.

If you can get through the academese, that’s highly complimentary. But, like any cultural product, Stevenson’s work “still upholds many of the colonial stereotypes typical of fin-de-siecle Western literature.” He was a product of his time – as we all are.

If the worry is that the research will change how we look at hitherto beloved classics, then why is that a bad thing? Our perceptions of cultural texts like art, TV programmes, plays and books, change all the time. To read a book critically – and be informed about its impact – doesn’t denigrate it as a work of literature.

Reading critically and with an awareness of context is essential. The uncritical acceptance of a book just because it’s a literary “classic” is bizarre. That kind of cultural deference doesn’t protect texts, it helps them become outdated for potential new readers.

And that’s the odd thing about the backlash to this project: it’s helping to continue the legacy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s work. The project statement says: “This interdisciplinary project explores the legacies of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pacific writing, investigating the relevance of his work to contemporary readers in Samoa, Scotland and Hawaii, and producing new art and poetry inspired by the three short stories published in Stevenson’s 1893 collection Island Nights’ Entertainments.”

I do wonder whether the people going apoplectic about this project have even bothered to look it up. It’s introducing Stevenson’s work to new readers and showing its relevance – as well as its problems – for a new audience. Even the most conservative “bah humbug” types who wouldn’t pay a penny for Arts and Humanities research must see the value in that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments