Rape culture at private schools isn’t about to change – parents are paying for this sense of entitlement

Any school attempting to undo rape culture within its walls must start from the recognition that an anti-sexist campaign represents a direct unpicking of the very patriarchal hegemony that boys’ private schools were set up to perpetuate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The winners of the prestigious debating competition known as Schools’ Mace reads like a roll call of the most well-known fee-paying boys’ schools in the country.

Eton, Winchester, Dulwich College, St Paul’s, Haberdashers’ Aske’s and City of London all appear in the competition’s 62 editions. It has been won by a fee-paying school on 41 occasions, 29 of which by schools that only admitted boys at the time of victory.

No subject is taboo; no topic is too emotive. In short, if you were determined to produce a young person ruthlessly capable of eliminating opposition to his actions through a combination of charm, powers of persuasion and limited appetite for empathy or compassion, you would train them in rhetoric and debate. And if you wanted to give them the best possible training, you would send them to an all-boys’ private school.

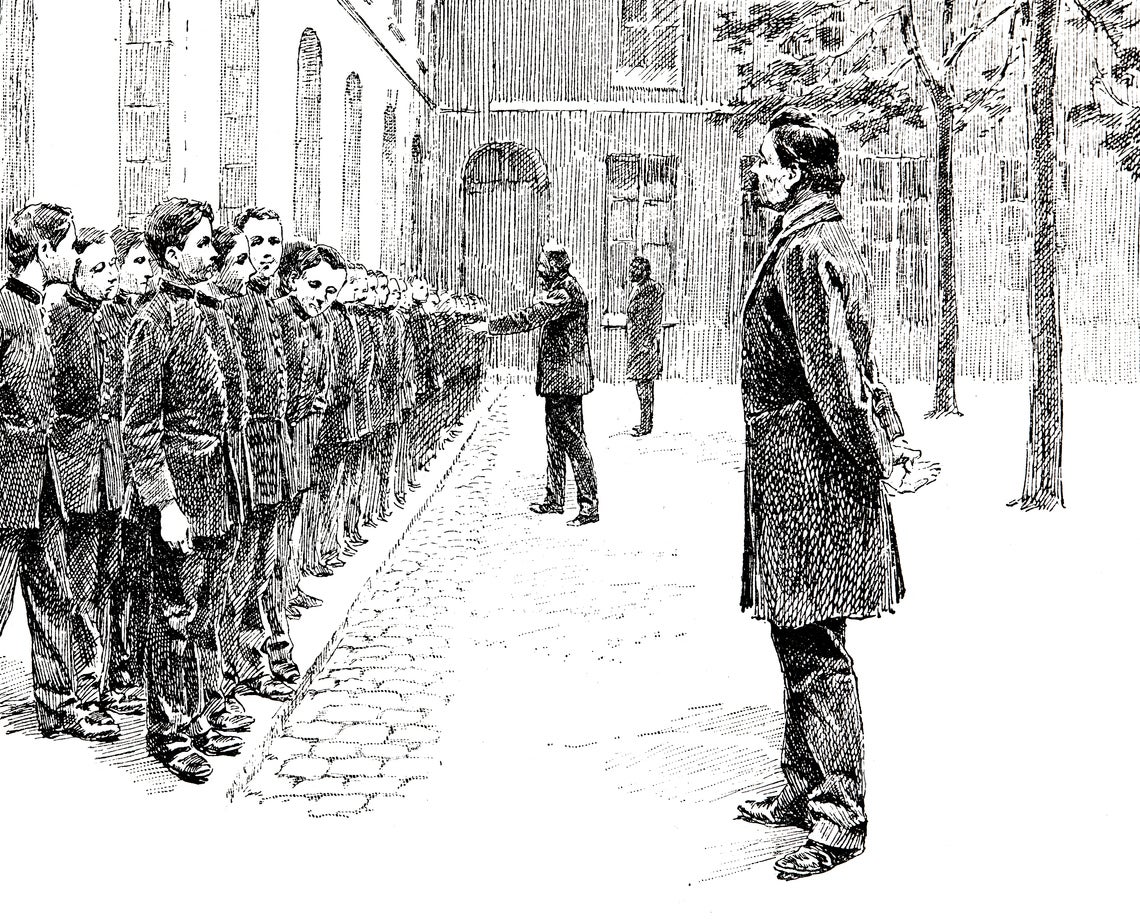

We should not be surprised by this conclusion. Journalists Robert Verkaik and Nick Duffell have written elsewhere about how the English boys’ school was reformed in the Arnoldian image to produce servants of a growing British empire some 200 years ago.

These schools produced young men ready to act as diligent public servants in far-flung climes, perfectly capable of smoothing relations with querulous subjects through charm and reason, but largely untroubled by the debilitating influence of compassion or empathy. While the goals that their charges pursue may have changed in the last 50 years, the fundamentals of their mission have not.

The atmosphere of competition, which parents are paying for – so that their son might become the most analytically incisive, the most charismatic, the most tactically astute or the most disciplined – results in students capable of extraordinary achievements. But in my experience, these achievements can come at the cost of humility and compassion.

Understanding this aspect of boys’ private school education is integral to understanding the huge amount of the anger directed at students and alumni from some of the country’s best schools in the wake of Sarah Everard’s tragic death.

The Instagram page Everyone’s Invited has, over the last few weeks, compiled thousands of testimonies from survivors of sexual harassment and violence, broadcasting them to an audience of 35,000 followers and attracting the attention of the national press.

While a wide variety of schools, colleges and universities have been mentioned, survivors have identified boys from top, historically all-boys’ private schools, such as Dulwich College, Westminster, Eton and St Paul’s as the main perpetrators in a high number of cases, some of which stretch back as far as the mid-1980s.

Read more:

Recent stories on the account have pointed to a “vile response” to survivors’ testimonies from certain cohorts within west London independent schools. There have been allegations that staff and procedures at these schools are, at best, ineffectual and at worst, active contributors to the rape culture found within them.

Newly private schools with an all-male background fare little better: Highgate and Latymer Upper are both named repeatedly across the testimonies, and schools with mixed sixth forms, such as Westminster School and King’s College School (KCS), have also faced detailed allegations of pervasive rape culture.

One ex-KCS student who joined from an all-girls’ school for sixth form told me: “The boys exhibited a profound sense of entitlement that was inherently gendered. These boys had been told they were brilliant in so many ways, and in a largely single-sex, fee-paying environment, this became an intrinsically posh, male thing.”

Reading these testimonies as an alumnus of a boys’ private school filled me with a feeling of nauseating recognition. Not only could some of the events outlined be traced back to contemporaries I knew by name, the atmosphere and attitudes that had facilitated them chimed perfectly with my memories of the school from around 10 years ago.

Rape culture was ubiquitous and systemic. From the married teacher revered by students for propositioning a sixth former at the girls’ school after the leavers’ ball, to the chauvinistic jokes that boys shared and the school society posters staff indulged, there was a pervading sense that women’s bodies were just another thing that boys like us were entitled to.

There was a sense we would be able to defend ourselves eloquently (and therefore successfully) against any emotion-filled accusation of sexism.

Irrespective of individuals’ actions or lack thereof, it’s clear to me we were all complicit in a culture of vicious misogyny. From what Everyone’s Invited indicates, little has changed.

The response from schools has been swift. Heads have sent emails to alumni; petitions and accounts have been accepted gratefully; leaders have held emergency whole-school assemblies over Zoom; old boys have signed open letters disavowing the culture they absorbed and perpetuated.

Yet no matter how far these gestures go, no matter how scrupulous the efforts to reform, the fact remains that any move towards producing more compassionate, empathetic young men, sensitive to their own privilege, represents a fundamental disruption of the tacit contract that has existed between paying customers and private schools for hundreds of years.

Any school serious in its attempts to undo rape culture within its walls must start from the recognition that an anti-sexist campaign represents a direct unpicking of the very patriarchal hegemony that boys’ private schools were set up to perpetuate. It would look like less time on Latin and more time on bias training. It would look like listening exercises and mandatory consent workshops. It would look like zero tolerance for sexual harassment and training in emotional intelligence and conflict management.

All of this would take time away from the usual cut and thrust of academic life that has gone on at these schools for years. The resultant stagnation or decline in exam results would accelerate the existing slide in private schools’ share of offers from top universities and their stranglehold over the highest-paying jobs.

With many schools taking a financial hit last year after paying out fee rebates, how many institutions will be willing to commit to such a strategy?

The school I teach at now is a world away from my alma mater. Forty-four per cent of our students are eligible for pupil premium funding, over 70 per cent speak English as an additional language and we have had only two students take up Oxbridge places in the last four years. But everywhere I look, I see boys and girls learning together as equals.

As a teacher, it is difficult to accept that the moneyed entitlement with which I was surrounded in my youth would give my students an enormous academic boost, but that it could not do so without fatally compromising the respect and empathy I see them show one another every day.

If I had to choose, I would rather have a child here than one destined for private school and Oxbridge, who thinks women’s bodies are just another topic up for debate.

Will Yates is a teacher at a community school in west London. He writes about access to higher education and reducing the gap between the independent and maintained sectors for ‘Tes’ (formerly ‘Times Educational Supplement’) and other platforms

This article was co-published with Private School Policy Reform

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments