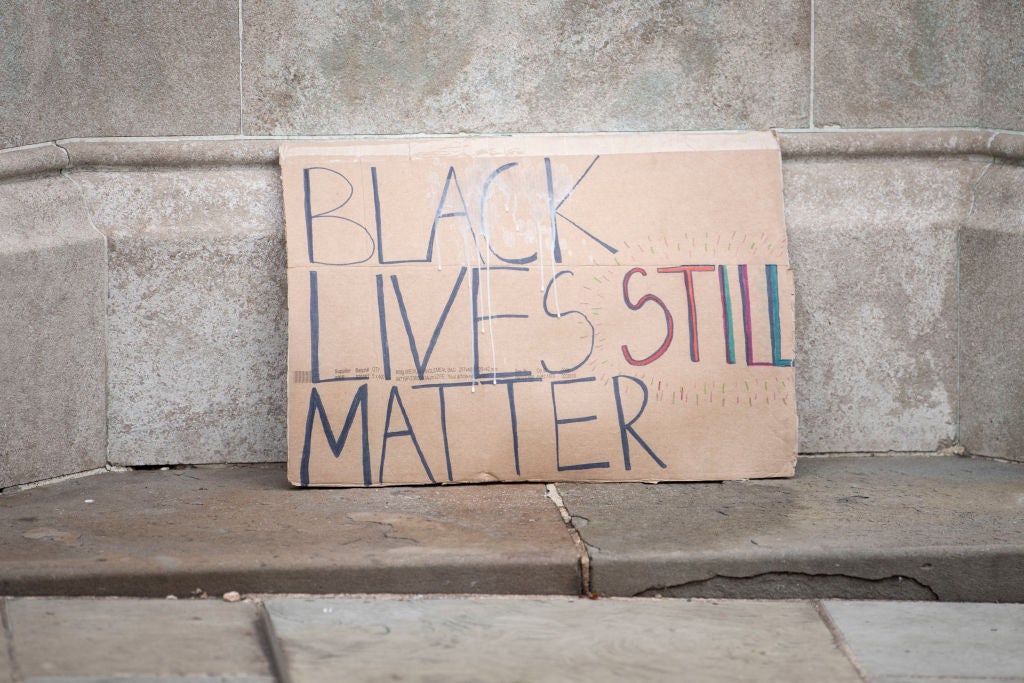

Body cams and parenting styles will not solve systemic racism

The new government-initiated report denies systemic racism exists, but campaigners should not lose heart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the defining features of racism is the desire to avoid eye contact with the problem. This strategy can be seen in full effect in the new report from the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. It finds no evidence for institutional racism, let alone the broader phenomenon of systemic racism.

Systemic racism exists where society’s laws, institutional practices, customs and guiding ideas combine to harm racially minoritised populations in ways not experienced by white counterparts. The report suggests that racial disparities have little to do with systemic racism. Instead, racial disparities can be remedied through more competent “race management” and fixing “cultural flaws” of some racially minoritised populations.

As a result, the Commission is silent on reducing or removing some police powers and instead suggests more use of police body-worn video as the way to increase the legitimacy of stop and search. But, this recommendation will do little to change the way that black people are unjustly over-scrutinised and over-sanctioned by law enforcement.

Elsewhere in the report, the focus is on perceived deficits among those experiencing racism. For example, the Commission recommends research on “cultural attitudes and parenting styles”. Here, the inference is clear: it is individuals and families that must self-improve rather than systemic and contextual forces that they have to navigate.

Campaigners should be challenging line by line the Commission’s flawed analysis and the insufficiency of its proposals. But it’s important for the ongoing struggle of racial and social justice to understand the broader question of why in the Commission and in wider society there is such an aversion to seeing the causal link between systemic racism and racial disparities.

In particular, we have to think about the various needs served by the current racial order and the deep problems caused by facing up to the systemic and designed nature of our racial malaise.

Read more:

Systemic thinking shows that social hierarchies have less to do with individual merit and are better explained by the designed contexts and circumstances that face different populations. But as the late campaigner and novelist Toni Morrison stated, facing systemic racism leaves people with fundamental questions:

“Are you any good? Are you still strong? Are you still smart? Do you still like yourself?”

These kinds of questions require white people to confront the relative benefits and privileges that they secure on account of systemic racism: an accounting exercise with which few want to engage.

More broadly, the existing order of things can provide solace and reassurance to a former world power like Britain trading on past “glories”. In this context, the instinct – one that can apply to people of any colour – is to cling on to national myths, such as British “fair play”. These myths tell us that everything is okay as well as deny the existence of any real need to change our collective life.

It is in this national context that the Commission’s work takes place, and its findings reflect a political situation where even minor changes in the old racialised order can lead to hyperventilation. For example, the removal of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol or the suggestion of an instrumental version of “Rule Britannia” at the Last Night of the Proms were turned into battlegrounds in the phoney “culture war”.

Finally, the pushback against systemic racism is because of the scope and scale of change that it demands. Systemic racism cannot be overturned through a bit more diversity or by corporations producing slick solidarity statements on Black Lives Matter. What is needed is a much more fundamental rethink about how we organise and distribute society’s resources, benefits and sanctions. And that takes will and imagination.

While it may not be easy to overturn the denial of systemic racism, campaigners should not lose heart. It is important to build public literacy on systemic racism. That means more than repeating the term and explaining in more vivid ways how it operates. Furthermore, there is much work to do to step into the future by developing blueprints for new systemic arrangements that will deliver anti-racist and other social justice outcomes.

These efforts won’t change the mind of the “anti-woke” zealot. But they may make it harder to justify systems-blind approaches to social change. In turn, we can be more ambitious about the change to come and the systemic remaking required to deliver it.

Dr Sanjiv Lingayah is an independent researcher, writer and consultant. He is the author of Race on the Agenda’s It takes a system: The systemic nature of racism and pathways to systems change

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments