Rachel Reeves had to go to China – and this is what they made of her

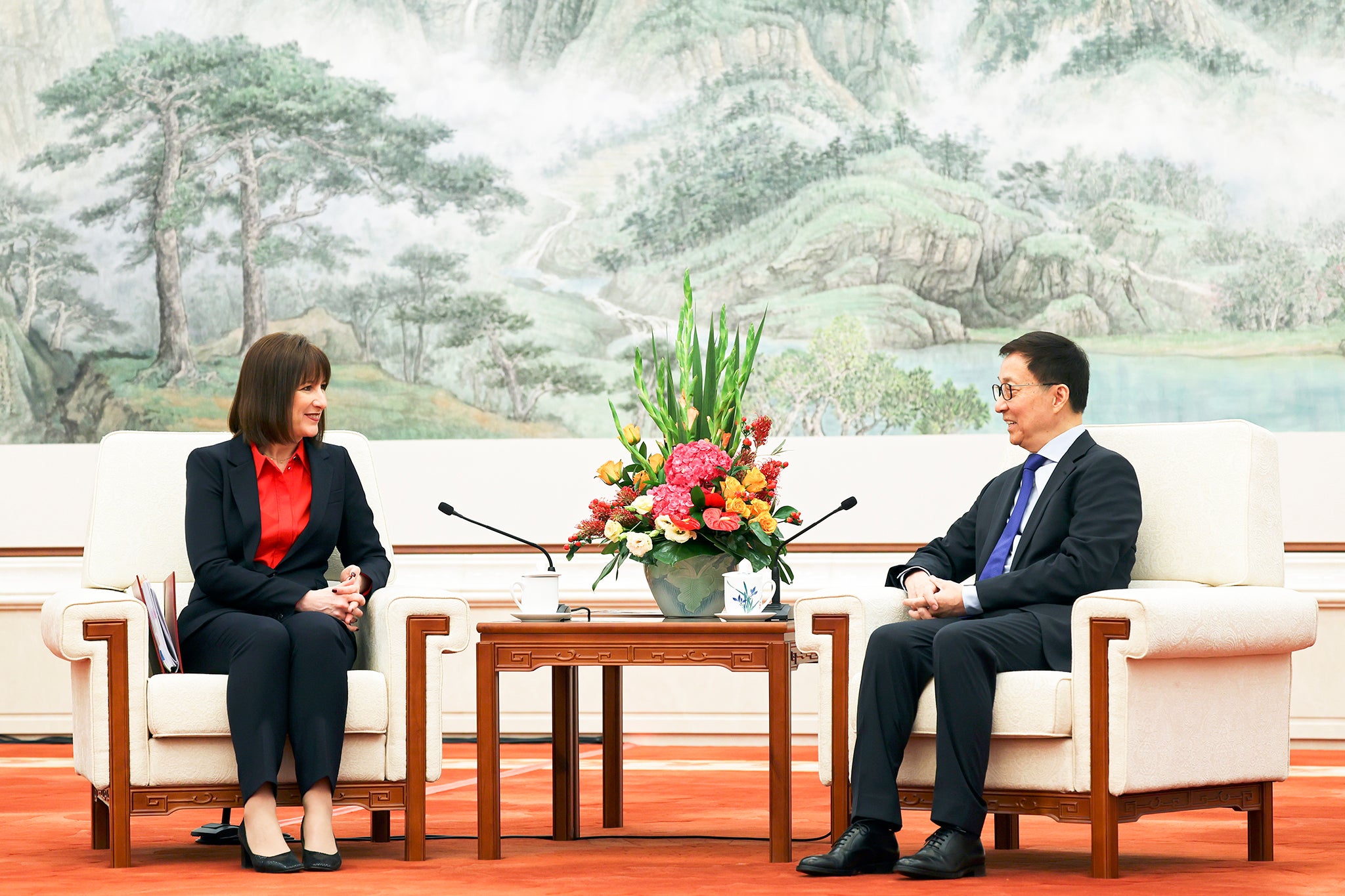

There’s a telling photograph of the chancellor which shows her sitting attentively, briefcase tucked on her chair, while the Chinese vice-president holds forth in front of a classical landscape mural. Neither is touching their porcelain teacups. China expert Michael Sheridan says a picture can sometimes be worth a thousand words

Let’s be clear. Rachel Reeves had to go to China.

The chancellor went to promote Britain and to win business. Staying at home would not have saved the pound. It would have looked like weakness – one thing the Chinese regime will always pounce on. So much for the good bit. My doubts creep in afterwards...

Selling Britain is one thing, selling out is another. We don’t know what was said face to face, but we can be pretty sure it was nothing that would offend the prickly hosts. I have been on a few of these junkets and they follow a path as well trodden as the Great Wall.

There’s a telling photograph of the chancellor, issued by the official Chinese news agency, which shows her sitting attentively, briefcase tucked on her chair, while the Chinese vice-president Han Zheng holds forth in front of a classical landscape mural. Neither is touching their porcelain teacups.

Such images are meant to convey to the Chinese public that the foreigners have come to pay tribute and beg favour from a mighty power – as did the first British envoy, Lord George Macartney, in 1793.

He was sent on his way by the Qianlong emperor with an edict that still resounds with doomed magnificence: China “never valued ingenious articles” and did not have “the slightest need of your manufactures”.

Accordingly, the emperor advised King George III “to act in conformity with our wishes by strengthening your loyalty and swearing perpetual obedience so as to ensure your country may share the blessings of peace”.

The monarch’s reaction is not recorded, but Anglo-Chinese diplomacy has moved on and trade is now worth more than £87bn a year, British statistics show.

The question is whether visits by politicians contribute anything to the vigour of business between the two nations.

Chris Patten, the last governor of Hong Kong, points out that trade boomed even while Chinese propaganda tore into him for expanding democracy as Britain prepared to bow out in 1997.

Soon afterwards, Tony Blair paid a ritual visit to Beijing and Shanghai, trailed by a glowering Alastair Campbell, Blair telling us on the flight that the leaders he had met were “reformers”.

On arrival in Hong Kong, Campbell delivered a ferocious press briefing to trash the local democrats, who had the temerity to suggest China could not be trusted. Some are in jail today. Podcast, anyone?

Then came the unfortunate Gordon Brown, whose visit was exquisitely timed to coincide with a financial crisis at home when the Northern Rock bank collapsed. To say he was distracted was an understatement.

As for David Cameron and his chancellor, George Osborne, their embarrassing emollience towards the new emperor of China, Xi Jinping, and his courtiers has been so well documented that Whitehall is desperate to forget the words “Golden Era”.

My doubts multiply when I look at the usual suspects in the supporting cast with Reeves in China. It is the same lineup – in some cases, heaven help us, the same faces – of bankers, insurers, financiers and consultancies for whom El Dorado is always just around the corner if only we would shut up about awkward subjects like tyranny, genocide and war.

One cannot blame the business people for pursuing their interests. They may be striving to save a great bank doomed by geopolitics or to defend a fintech startup that might be consumed by rivals in China. All credit to them for that.

Tom Tugendhat and Iain Duncan Smith, neither of them anti-capitalists, have torn into the chancellor and her delegation for performing a “kowtow” (which Lord Macartney, famously did not). They say it all reeked of appeasement, while Mr Tugendhat argued that she should have gone to Taiwan.

Many Chinese people have the highest regard for both Tory politicians, who have been sanctioned by Xi’s regime for their decency and their principles. But on this occasion, they seem a bit quixotic. Here’s why.

The world is a far more dangerous place than in previous junket times. In a week, Donald Trump will take office as president of the United States. He will start a tariff war, whatever Britain does. We are already in a new cold war against the autocracies. China is covertly on the battlefields of Ukraine and the Middle East, while preparing for a hot war against the US and its allies in the seas around Taiwan. The risks are off the scale.

The fear of Joe Biden and his team was that Xi Jinping did not get to hear hard facts because he was encircled by courtiers. Despots do not have a great record of risk calculation. Team Biden took every opportunity to get into the room with Xi or his counsellors to urge “the blessings of peace”, in the phrase of the Qianlong emperor. So should everybody else. Right now, every little helps. And that is why Rachel Reeves had to go to China.

Michael Sheridan, longtime foreign correspondent and diplomatic editor of The Independent, is the author of ‘The Red Emperor’, published by Headline Press at £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments