Dry, meandering, heavy on small detail: Prince Harry’s day in court was more ‘bust’ than ‘blockbuster’

Even with the most celebrated characters, courtroom dramas need a higher-octane plot than this one, writes Tom Peck

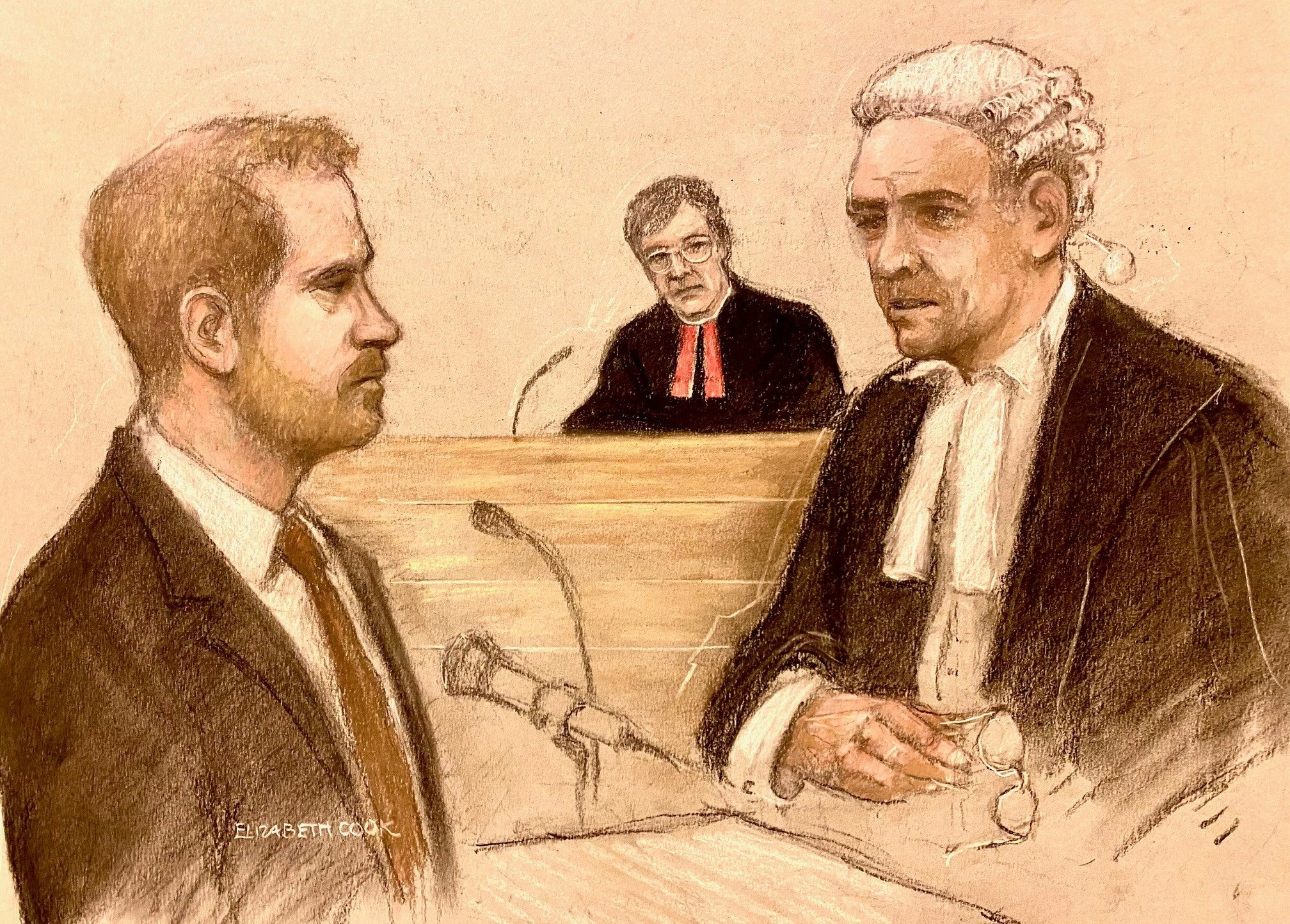

In a neon-strip-lit room, in front of a television audience of zero, the prince placed his hand upon the Holy Bible.

There was no archbishop, no golden robes, and no promise to govern the people with justice and mercy.

Only the common oath for Prince Harry. Common, yes, but very rare. You have to go back more than a century for the last time a senior royal was sworn in as a witness in a major court case. He cleared his throat, fixed his eyes in front of him, and swore that the evidence he would give would be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth so help him God.

It was a blockbuster event. The snappers and the camera crews filled up both sides of the street outside London’s High Court, before curving around the corner and becoming almost indistinguishable from the Pret Club subscription-holders spilling out onto the street as they waited for their coffees in the morning rush.

But whatever state of breathless anticipation had been achieved did not last for long. Even with the most celebrated characters, courtroom dramas need a higher-octane plot than this one.

Prince Harry is, almost certainly, one of more than a thousand victims of “unlawful information-gathering” by the tabloid press. But he is one of a vanishingly small number who are refusing to be paid off, and he was absolutely determined to have his day in court. This was it.

But the problem is, it’s really all rather slow. The whole point of the cruelty of phone-hacking, as everybody even faintly interested in the subject knows by now, is that what might seem like a whole load of trivial tittle-tattle about the lives of famous people had profoundly damaging effects on its victims, who couldn’t work out how it was that photographers and reporters knew what they’d been doing – or worse, where to find them – and so stopped trusting even their closest friends and family.

Its seriousness is not to be underestimated. But it does lead to this: many long hours of listening to Prince Harry being asked in great detail about, for example, who did or didn’t know this or that about a lunch in Pizza Express in Fulham in the late Nineties, or where he and his brother did or didn’t go on a rock-climbing holiday, or what happened on his gap year in Australia, or what the school nurse said to him when he broke his thumb at Eton.

It most certainly does matter. The dedicated band of journalists, celebrities, and indeed former phone-hackers who have spent the last 15 years trying to get justice, which for them means nothing less than bringing down the whole tabloid empire, think the prince is their ace of trumps, precisely because he’s not bluffing and he’s never going to fold.

But it will have been a tough day’s viewing for them. At the heart of this particular court case, against Mirror Group Newspapers, are 33 stories that Harry alleges can only have come from “unlawful information-gathering”. So it didn’t necessarily help his cause, when it was put to him by the Mirror’s barrister, Andrew Green KC, that large numbers of the allegedly illegally obtained details in those stories had appeared in other newspapers days or weeks before. Or, in a couple of cases, were rather unlikely to have been obtained from phone-hacking on the basis that they had been published in 1996, two years before the prince had even had a mobile phone.

Mr Green’s shtick grew wearisome very quickly. He plodded through the boring details of a story that didn’t matter very much, and then wearily asked: “Is it realistic to claim that the article in the Daily Mirror has caused you any distress whatsoever?”

The prince, to his credit, usually replied: “Yes.” That it wasn’t the story that had caused him distress, but the paranoia about how they had got it.

He was also forced to admit, several times, that he hadn’t read the stories in question, as if that were some kind of slam-dunk. The point, though, was not whether he had read the stories himself, but the impact they had had on him, rendering him completely unable to lead anything like a normal life.

And to almost all of the questions, Prince Harry had a sharp answer. It may, strictly speaking, be up to him to prove that he was a victim of phone-hacking, but the people who absolutely know for sure are the Mirror journalists who wrote the articles.

“Who wrote that story?” he said, on at least 20 occasions. “You could put that question to them.”

He probably knows that’s not how the process is meant to work. But he also knows that it would be very easy for Mirror Group Newspapers to summon all its journalists and get them to explain the entirely legal means by which they acquired all these stories. Easy, that is, if it were true. But none of them, or almost none of them, are scheduled to appear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments