The winners and losers of British politics in 2024

It’s been an eventful year for our leaders, dominated by an election that left Tory casualties strewn on the battlefield after a well-fought Labour win. John Rentoul looks back at a seismic 12 months in politics

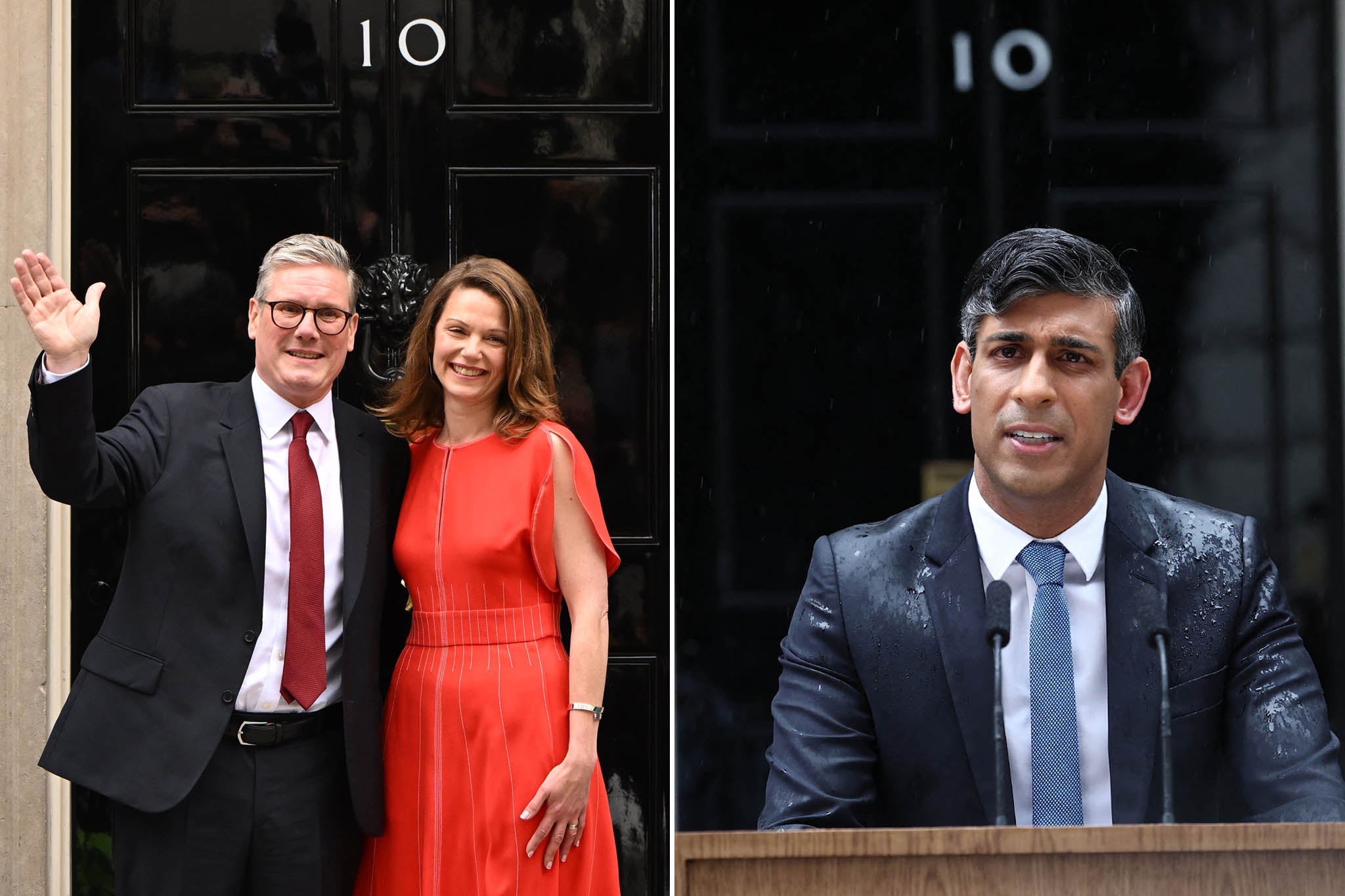

Keir Starmer and Rishi Sunak feature in the lists of the six winners and six losers in British politics in 2024, of course, but so do some of the backroom operators who helped them to victory and defeat.

What’s more, the splintering of party loyalties meant that a single election produced several winners, as the Liberal Democrats, Reform and the Greens also made gains on a battlefield strewn with Conservative casualties.

Then came the aftershocks, as the opposition had to find a new leader, and the new government struggled with early internal tensions, losing a chief of staff and a cabinet minister along the way.

Winners

1. Morgan McSweeney

The Labour leader’s chief of staff was set the task of winning the election, and he delivered a landslide. Labour’s vote was so efficiently distributed that the lowest share of the vote for a winning party since the war translated into the second-highest number of seats.

In Keir Starmer, McSweeney thought he had found a leadership candidate who could take the party back from the Corbynites; winning a general election seemed a long way off. Then the government imploded and Reform split the Conservative vote.

Even so, the Labour election campaign was disciplined and the voter-targeting was ruthless.

Next, after a three-month turf war, McSweeney became a double winner, ousting Sue Gray to take over as chief of staff in No 10. Now he is king of Starmer’s castle.

2. Keir Starmer

If McSweeney was a lottery winner who had ticked the “no publicity” box, it was Starmer who basked – all too briefly – in public acclaim. For all the carping about Starmer’s caution before the election and his unpopularity after it, he was the one who ended up as prime minister with a huge majority.

Starmer and McSweeney came so close to beating Tony Blair’s record majority that they had a surreal conversation in the lift at the election-night party in the Tate Modern about how “irritated” they were not to have exceeded his score. Victoria Starmer told them off: “This is just a ridiculous kind of conversation to be having.”

She was right. Theirs was an astonishing achievement that no one had dreamed possible even a year before.

3. Terry Jermy

“I was not expecting to win my election,” said Terry Jermy, the Labour MP for South West Norfolk, in his maiden speech in the Commons. He had stood as a candidate because he wanted to raise the issue of the failings of the NHS after the death of his father last year. A small business owner, as proprietor of About Thetford magazine, he had been a local councillor and became the first openly gay mayor of Thetford seven years ago.

The unpopularity of the Conservative MP, Liz Truss, and a four-way split vote with Reform UK and an independent candidate from the local “turnip Taliban”, who had been opposed to Truss from the start, propelled Jermy into parliament with 27 per cent of the vote, the lowest winning share in the country.

4. Dave McCobb

If Labour did well in the general election, so too did the Liberal Democrats, winning more seats – 72 – than at any time since their predecessor Liberal party in 1923. Theirs was a stealth campaign, knocking out Conservative MPs in the home counties on a platform of being nice, restoring social care and cleaning up sewage, fronted by an affable bloke falling off paddle boards.

The genius behind the Lib Dem campaign was McCobb, their director of field campaigns. He has been a low-profile local councillor in Hull for 22 years – although The Independent wrote about him when he masterminded the North Shropshire by-election campaign in 2021, when Owen Paterson, the former cabinet minister, resigned.

McCobb’s brilliant campaign puts the Lib Dems in a strong position in any hung parliament in the future.

5. Nigel Farage

The other election winner was Farage, who finally succeeded on his eighth attempt to make it into the House of Commons. Whether he would stand at all was touch and go. Rishi Sunak’s early election caught him off guard. He had taken a back seat in the Brexit Party, adopting the title of honorary president, and was planning to spend time in the US supporting Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

But the opportunity facing him was too good to miss, and Farage announced at a news conference in Clacton that he was returning as party leader and standing as parliamentary candidate there. Richard Tice, the party leader, smiled bravely for the cameras. Tony Mack, the displaced local candidate, said he was “disappointed” and “surprised”.

Since then, Farage has hit the publicity jackpot, with Elon Musk endorsing the claim that he will be the next prime minister and hinting at a $100m (£80m) donation to Reform.

6. Kemi Badenoch

The final winner of the year is the new Conservative leader, elected last month. The “breath of fresh air” seemed to run out of puff after defeating Robert Jenrick, but it is still astonishing that the party of tradition should have chosen a fourth female leader, a second non-white leader, and someone who seems so unlike a conventional MP.

For all Farage’s brag and bluster, the leader of the opposition has a better chance of becoming prime minister than the owner of an insurgent party whose views on everything except immigration are out of line with those of moderate voters.

Badenoch may be taking on “the worst job in British politics”, but she is more likely to emerge a winner than her Reform rival.

Losers

1. Rishi Sunak

Undisputed champion of the “loser” category, Sunak was doomed from that moment in January 2023 when he announced five promises that he could never hope to fulfil. In every week that followed he seemed more likely to fail, with the only question being the manner and timing of his being put out of his misery.

He tried to take control of events by surprising everyone, including most of his cabinet, by calling an early election. He was right and selfless to do so – giving up five months in office to try to reduce the Conservative losses. I think he succeeded, because even though the Tories were reduced to 121 seats, their worst ever showing, it could have been worse still. If the election had been later, prisoners would have had to be let out, Jeremy Hunt would have had to announce austerity spending plans, MPs would have defected to Reform, and the Tory party would have run out of money.

2. Liz Truss

The top loser of 2022, the shortest-serving prime minister of all time, features in the list a second time after losing her seat two years later. She also ought to be awarded some kind of additional prize for her refusal to accept defeat – a refusal that might in other circumstances have been heroic. This was the year she published her book, Ten Years to Save the West, which argued that she had been basically right all along and had been done in by “the blob”, including the Bank of England.

In the pantheon of the last five Conservative prime ministers – losers all – she also wins the lifetime achievement accolade. David Cameron lost a referendum. Theresa May lost her majority. Boris Johnson ran away rather than fight a by-election, and Sunak was crushed. But she outdid them all.

3. Sue Gray

Starmer thought it was a great coup to have hired Sue Gray, a civil servant at the heart of Whitehall, to help him prepare for government. But all it did was provoke a row about civil service bias – in return for little by way of getting ministers ready for office. “If you ever see any evidence of our preparations for government, please let me know,” said one anonymous adviser, days before Gray was moved as chief of staff in a dysfunctional No 10 to be the prime minister’s envoy to the nations and regions – a non-job that she eventually decided not to take up.

Earlier this month she collected her consolation prize of a peerage.

4. John McDonnell

When John McDonnell and Jeremy Corbyn stepped down after losing the 2019 election, McDonnell urged fellow members of the Socialist Campaign Group not to give the new leadership any excuse to purge them.

One by one, though, they were purged, or they purged themselves. Corbyn himself was suspended for refusing to accept the findings of an inquiry into antisemitism under his leadership. But McDonnell survived – until 18 days into the new government, when he misjudged the number of Labour MPs who would vote against the King’s Speech in protest against the two-child limit on benefits. He thought there would be too many for Starmer to take disciplinary action, but in the end, there were only seven, including McDonnell. They were suspended from the parliamentary party, and are unlikely to return.

He once said that membership of the Labour Party was “a tactic ... if it’s no longer a useful vehicle, move on”. The vehicle has finally moved on without him.

5. James Cleverly

The prize for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory goes to James Cleverly, the affable former home secretary and foreign secretary who took a commanding lead in the penultimate round of voting by MPs in the Conservative leadership election, only to crash out in third place in the next ballot.

In a parable of tactical voting, it seems too many of his supporters took his victory for granted and switched to voting for the candidate they most wanted him to face in the run-off. “Some MPs were trying to be too clever, especially some of the newbies,” a veteran former minister told The Independent.

As a minor recompense, Cleverly picks up the award for good loser, retaining his good humour. “Sadly, it wasn’t to be,” he said, but the support he had received made him “proud to be a Conservative”.

6. Louise Haigh

The transport secretary seemed vulnerable because she gave the Conservatives one of their few effective attack lines by agreeing a no-strings pay rise for train drivers already earning £60,000 a year. And she nearly scuppered the government’s big international investment jamboree by describing P&O in the present tense as a “rogue employer” when the company claimed to have reformed since firing its British workforce two years ago. Its Dubai-based owner briefly refused to attend the conference.

But she became the first cabinet minister to exit because of something else entirely. She claimed she had disclosed her conviction for fraud over a lost company phone, but Keir Starmer, who had been prepared to defend her, felt “there appeared to be gaps and loose ends in her account of what had happened that were at variance with what he had understood about the case”, according to a source.

We never found out what those “loose ends” were, or who leaked the story, but, at the end of last month, out she went.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments