The Philip Green injunction is proof that we need to get rid of NDAs for good

I have long since advised my clients that having an NDA was a sure way to cause trouble in the future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

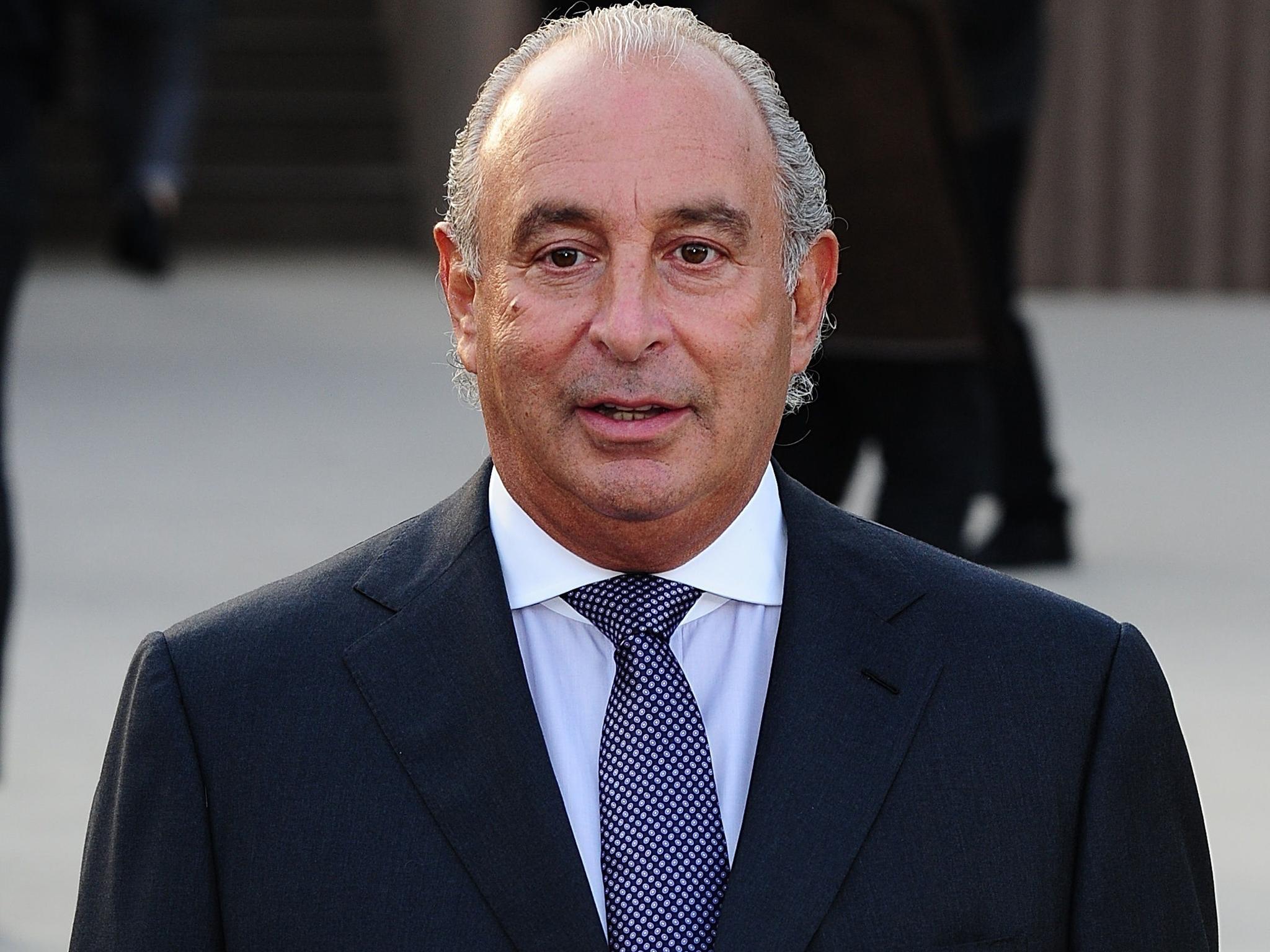

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Philip Green has been named by Lord Peter Hain as the person who successfully sought an injunction to prevent a newspaper from printing allegations of sexual harassment and racism against him. I am not in a position to say whether he is truly the person involved or not, but either way we will find out soon enough, notwithstanding any non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

The old adage goes that “everything hidden is meant to be revealed, and everything concealed is meant to be brought to light”. In short, NDAs often don’t work because secrets will out. We cannot help talking about them, and the bigger the secret, the more the talk. For example, consider Donald Trump’s alleged NDA with Stormy Daniels, over his alleged affair.

Nonetheless, lawyers have tried to compel opposing parties to keep secrets for years, and are still trying to do so. They developed NDAs of varying widths and lengths, sometimes with the best of intentions, just to resolve clients’ disputes – more often with the worst of intentions though – not just to avoid public opprobrium, but to dodge regulatory intervention, particularly when allegations of harassment or discrimination were made.

Almost invariably, they are sought as the price of early settlement of a claim that could drag on for years, though just occasionally, victims of harassment believe it in their interests to have a cloak of secrecy cast over their claims by such an agreement. Normally they should not worry about that, as the rules of procedure in the Employment Tribunal provide robust and tested controls to protect the anonymity of a claimant. So the Women and Equalities Select Committee chair Maria Miller MP was right to call for a deep review of their use and legality, following the committee’s report on sexual harassment in the workplace.

There is a really practical reason for this. Sexual harassment is predatory behaviour. Women know that, though not all men do. If it is to be stopped, it has to be called out. There is no other way. So whereas complaints and litigation operate to discipline such predators, NDAs have the opposite effect. If the NDA works, the alleged harasser will feel empowered to try again. I know this from experience as a junior barrister making a living many years ago, when I became aware of repeated complaints against a senior manager of a major department store who was picking on young female recruits. But you do not need this direct experience to know it’s likely to be true.

Women need to be safe at work just as men do. We have to stop all kinds of harassing and bullying behaviour – there is a national public interest in addressing this. Sometimes bullies and harassers have their own sad stories making them the person they are, but that is no excuse for avoiding the protection of their victims.

Lawyers have a really important role to play here. Barristers are required to act with honesty and integrity, to maintain public confidence in the profession, and to be open and co-operative with regulators. Similar obligations are imposed on solicitors by the Solicitors Regulatory Authority. All lawyers must recognise harassment is often not merely a matter between two individuals, but a criminal act in which the state has a direct interest. Covering it up with an NDA is, therefore, a pretty risky thing to do.

The law’s own regulators are onto this. They have been called to act by the Women and Equalities Committee. Legal regulators the Bar Standards Board and the SRA, aim to make it much more difficult for NDAs to be proposed to clients, then drafted and agreed. That is not only an example of good regulation, it is also wise.

I have long since advised my clients, having an NDA is a sure way to cause trouble in the future. If disclosure happens, the “cover up” that was intended by the NDA becomes the story, or at least adds spice to the allegations. And despite Mr X’s success in the Court of Appeal in securing an injunction against the Daily Telegraph, NDAs are notoriously difficult to enforce.

Killing off NDAs altogether, at least in relation to claims of harassment or discrimination – or any alleged breach of regulatory rules or crimes – cannot come soon enough. Society will be better off for it, even though it may mean some disputes take longer to resolve or have to be litigated to a final conclusion.

Robin Allen QC is chair of the Equality and Diversity and Social Mobility Committee of the Bar Council of England and Wales