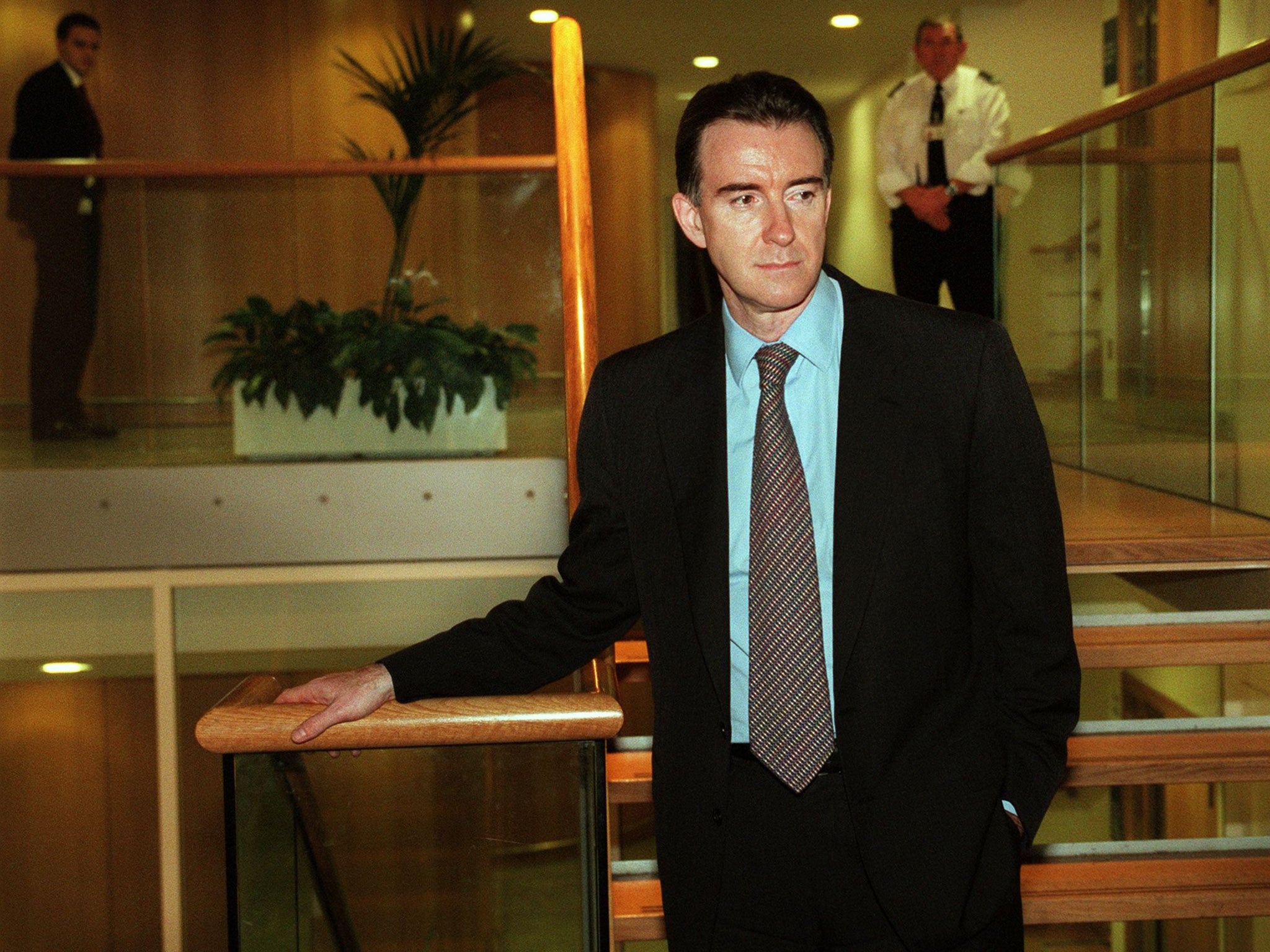

The Peter Mandelson Dim Sum Supper and predictions for the year ahead

Having promised to approach our predictions for 2016 with more diligence and humility, we proceeded to make our reckless forecasts pretty much as before

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

This year’s Peter Mandelson Memorial Dim Sum Supper was a serious occasion. Before we could begin – the venison puffs were highly commended – the diners had to walk round the table anti-clockwise three times, flagellating themselves with birch switches.

The event dates from 23 December 1998. That was when I was lunching with a group of friends in Soho and news came through – in those days, by pager – that Mandelson had resigned from the Cabinet. By coincidence, the same group were lunching just after Christmas two years later, on 24 January 2001, when Mandelson resigned again. Since then, it has been an annual event, and its main business consists of predictions for the year ahead.

Hence the solemnity at the start. This year has been a disastrous one for the Dim Sum Group. Last Christmas, although we predicted that the Conservatives would be the largest party in the House of Commons, we thought Ed Miliband would be Prime Minister by now. Some of our number – the minority who had insisted that David Cameron would continue in office – tried to avoid the self-flagellation ritual, but they were required to take responsibility for other duff forecasts. Such as 18 seats – the average of our estimates – for the Scottish National Party and 30 for the Liberal Democrats (the actual results were 56 and eight). What is more, we thought that if Cameron stayed at No 10, Yvette Cooper would be Labour leader.

Having promised to approach our predictions for 2016 with more diligence and humility, we proceeded to make our reckless forecasts pretty much as before. First business was the London mayoral election: a majority thought Zac Goldsmith would win for the Conservatives, despite being too rich in a Labour city; a minority plumped for Sadiq Khan. In the Scottish Parliament elections, we were unanimous that the SNP under Nicola Sturgeon would advance on the nine-seat majority it won in 2011.

Next business, chronologically, is probably the EU referendum. A majority thought it would be in September, a minority said June. We were agreed as to the outcome: the nation, swayed by the Prime Minister’s recommendation, would vote to remain in the EU. The range of our estimates for the “Remain” share of the vote was surprisingly narrow, from 53 to 57 per cent. In other words, a much closer result than the 67 per cent vote secured by Harold Wilson for his renegotiation in 1975, and more like the 55 per cent by which the Scottish referendum was decided, which failed to settle that question for five minutes, let alone for a generation.

Then we turned to the US presidential election. Having learned from the great Professor Philip Tetlock – author of Superforecasting, one of my favourite books of this year – to know my limits, I refused to predict this one. British journalists may not be that good at predicting British politics, but we are hopeless at the American stuff. So, I don’t know. Other members of the group seemed more confident, but they divided between Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio as the Republican nominee.

In any case, my fellow diners were all convinced that Hillary Clinton would defeat whomsoever the Republicans should send in for the slaughter. Recalling confident American predictions in 1991 that the Democrats were merely choosing which unfortunate would lose to George Bush Snr in 1992 (they chose Hillary’s husband), I refused to predict that one either.

Next on the menu, after the crispy duck and some more dim sum: the next leader of the Conservatives and therefore the next PM. A majority verdict was for Boris Johnson, with a minority opting for George Osborne. The general view was that if Johnson could win the support of enough MPs to make it into the top two and therefore on to the ballot paper, the party members would choose him. So, the decisive moment is Osborne’s struggle to push someone else – Theresa May, Nicky Morgan or Sajid Javid – ahead of Johnson in the MPs’ vote.

Finally, we came to the Labour Party, where the main question was how long Jeremy Corbyn would last. No one thought he would be deposed in the coming year. His support among Labour members and supporters is too strong. Indeed, we all agreed he would continue to be leader until 2020, but then the room divided. I found myself in the minority again, arguing that he would lead Labour into the election. My view is that, under his leadership, Labour would win a smaller share of the vote in Great Britain than under Ed Miliband (31.2 per cent), Gordon Brown (29.7 per cent) or Michael Foot (28.3 per cent).

The majority view, however, was that he would cease to be leader shortly before the election. And we were just discussing who would take his place when the bill arrived.

To be continued in a year’s time….

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments