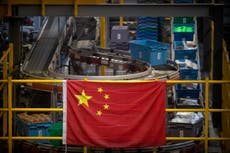

America and Britain are the big losers on the world stage as they fail to control Covid

The pandemic is accelerating the shift of power to nation states and an Asia-centred world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lockdowns are unnecessary if the use of masks is practiced by 95 per cent of the population, says Dr Hans Kluge, the World Health Organisation’s European chief. This is good to know, though it is a pity that the WHO did not make the point more forcefully in March as the pandemic was exploding across Europe and the world.

The necessity for face masks had been expressed at the time, but the advice to use them came from a source that European and American leaders dismissed as politically unacceptable. As Britain and other European states were going into lockdown, Dr George Gao, director-general of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention – the main Chinese public health body – was asked in an interview on 27 March about what he believed were the mistakes being made by other countries trying to control the epidemic. He replied that “the big mistake in the US and Europe, in my opinion, is that people aren’t wearing masks”.

His opinion should have been taken seriously since China, notwithstanding the suppression of the Uighurs and democracy in Hong Kong, along with other east Asian countries, were succeeding in bringing the coronavirus epidemic under control. But instead of drawing on this experience, the new cold war against China ensured that any positive news from there was ignored, disbelieved or derided. China’s initial concealment of the epidemic was highlighted, and its success in containing it was disregarded. When China’s return to normality was mentioned, it was attributed to autocratic rule that could not and should not be emulated elsewhere. In point of fact, the Chinese achievement resulted largely from old-fashioned public health measures, with a heavy emphasis on test-and-trace and travel bans, pursued with great energy and with the mobilisation of vast resources.

Refusal to learn from a successful campaign against the coronavirus because it was carried out by a political rival was self-destructive for Europe and the US, but their response should not have been unexpected. Before the pandemic, we were already living in a deglobalising world where individual nation states jostle to enhance their power. Rule-based international institutions and coalitions from the WHO and WTO to the EU and NATO were ebbing in influence. The epidemic has only flood-lit the fact that re-energised nationalism is the spirit of the age from America to the Philippines and from China to Brazil.

The dominance of this trend has become clear since 2016, the decisive year that saw the UK voting to leave the EU, the US choosing Donald Trump as president, and Turkey transforming itself into a full-blown autocracy in the wake of a failed military coup.

But Covid-19 has given history a powerful nudge down the roads it was already taking. If a global threat like a deadly virus that knows no borders had emerged a decade earlier, it would probably have provoked a global response under the aegis of the US. But after the coronavirus emerged in Wuhan at the end of 2019, the opposite happened and it speeded up deglobalisation – and not just because of xenophobic rants by Trump or the mini-Trumps that have been popping up around the world.

Nor was it solely among populist nationalist regimes and autocracies that “health nationalism” has become the order of the day. A study, called “Geopolitical Europe in Times of Covid-19” by Mark Leonard of the European Council on Foreign Relations, notes that the shock of the epidemic provoked the same response by nation states within the EU as it did among those outside it: “It was clear that none of the great powers were looking to the multilateral system to provide an answer [to the epidemic]. As the death count rose, every country acted as if it was on its own, closing borders, stockpiling medical equipment, and introducing export controls.” This pushback against political and commercial globalisation continues, affecting everything from cross border migration, international travel and tourism to global supply chains and the distribution of vaccines.

Another nudge to history delivered by Covid-19 is the shift of the crucial arena of world politics from Europe to Asia. The EU is stumbling politically, displaying once again the weaknesses it showed during the 2008 financial crisis and the refugee crisis sparked by the Middle East wars. Brussels may appear like a behemoth to a self-marginalised Britain as it negotiates the terms of its exit from the EU, but the EU is itself becoming more marginal in the world.

Can any rough guide to winners and losers in the year of Covid-19 be drawn up at this stage? America and Britain are both bad losers: Trump and Johnson had been divisive and demagogic before the epidemic struck, but when it did strike it dramatically exposed the dysfunctional nature of their governments and their personal inability to deal with a real crisis. This sense of chronic breakdown is exacerbated in the US by Trump’s fraudulent claims to have won the presidential election, giving a toxic foretaste of a permanently divided and destabilised America.

For Britain the post-Covid-19 and post-Brexit future looks even bleaker than in the US. The latter is a superpower that can make gross mistakes in a way that Britain, as a smaller player, cannot afford to do.

Britain’s final exit from the EU was always going to be difficult, but coronavirus means that it is entering a particularly forbidding political landscape. Brexit in itself is not so peculiar: many nations have sought self-determination, propelled by dreams of getting back control, but Britain has traditionally relied on foreign alliances in war and peace. It has stood alone, notably against Napoleon and Hitler, only because its allies had been defeated and it had no other option.

Britain will try to re-glue its relationship with the US and Europe by becoming a doughty spear carrier for both in the deepening cold war against Russia and China. This explains Johnson’s £16bn increase in the defence budget over the next four years, despite the calamitous damage inflicted on the economy by the epidemic. Gestures like this and a bit of threat-inflation solidify alliances, but they are scarcely an original strategy: Tony Blair tried a similar approach with disastrous results by joining US military ventures in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Britain is facing one of the most serious crises in its history under the least serious leadership it has ever known. The Brexiteers turned out to be a bigger danger than Brexit. Every week brings fresh evidence of their blunders, shady dealings and blindness to the dangers of a deglobalising world in which Britain will be a small fish trying to navigate the political oceans.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments