Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For sheer unadulterated spectacle, there is nothing to beat election night across the television channels. A royal wedding pales by comparison and the Champions League Final is the merest sideshow. As to why the sight of some grim-looking politician struggling to disguise the fact that the aspirations of the past half-decade have been blown away by a single exit poll, the explanation lies in the fact that here is not only a continuous eight-hour narrative, but one capable of springing countless incidental surprises and endlessly scattered fragments of human drama. Even now, for example, five years after the last small-hours stake-out I can still recall the fury in the voice of the defeated Liberal Democrat MP Lembit Opik as he rebuked Jeremy Paxman for being patronising or the black-clad surrogate hitman who, standing behind Gordon Brown at the Kirkcaldy count, managed a clenched-fist salute for the full five minutes that it took the departing prime minister to deliver his acceptance speech.

Inevitably, change was in the air. “It’s all very modern now,” ITV’s Alastair Stewart somewhat loftily remarked when, at 9.45am, it was brought home to him that the Labour Party’s HQ was now located in Victoria rather than at Transport House. Fatigue was not an excuse – Stewart had only lately replaced Tom Bradby in the anchor’s chair – but the deduction was correct. It was all very modern, from the jazziness of the Sky graphics to the rumour-mongering text messages and insinuating tweets that flew in from all sides. Jeremy Vine’s virtual House of Commons, at which, I regret, my 15-year-old son laughed uncontrollably, looked as if it had been imported wholesale from Silicon Valley and his tumbling Lib Dem house of cards ended up resembling an architectural suspension which some enterprising beneficiary of the Arts Council’s largesse might soon seek to erect in a vacant hangar at Tate Modern.

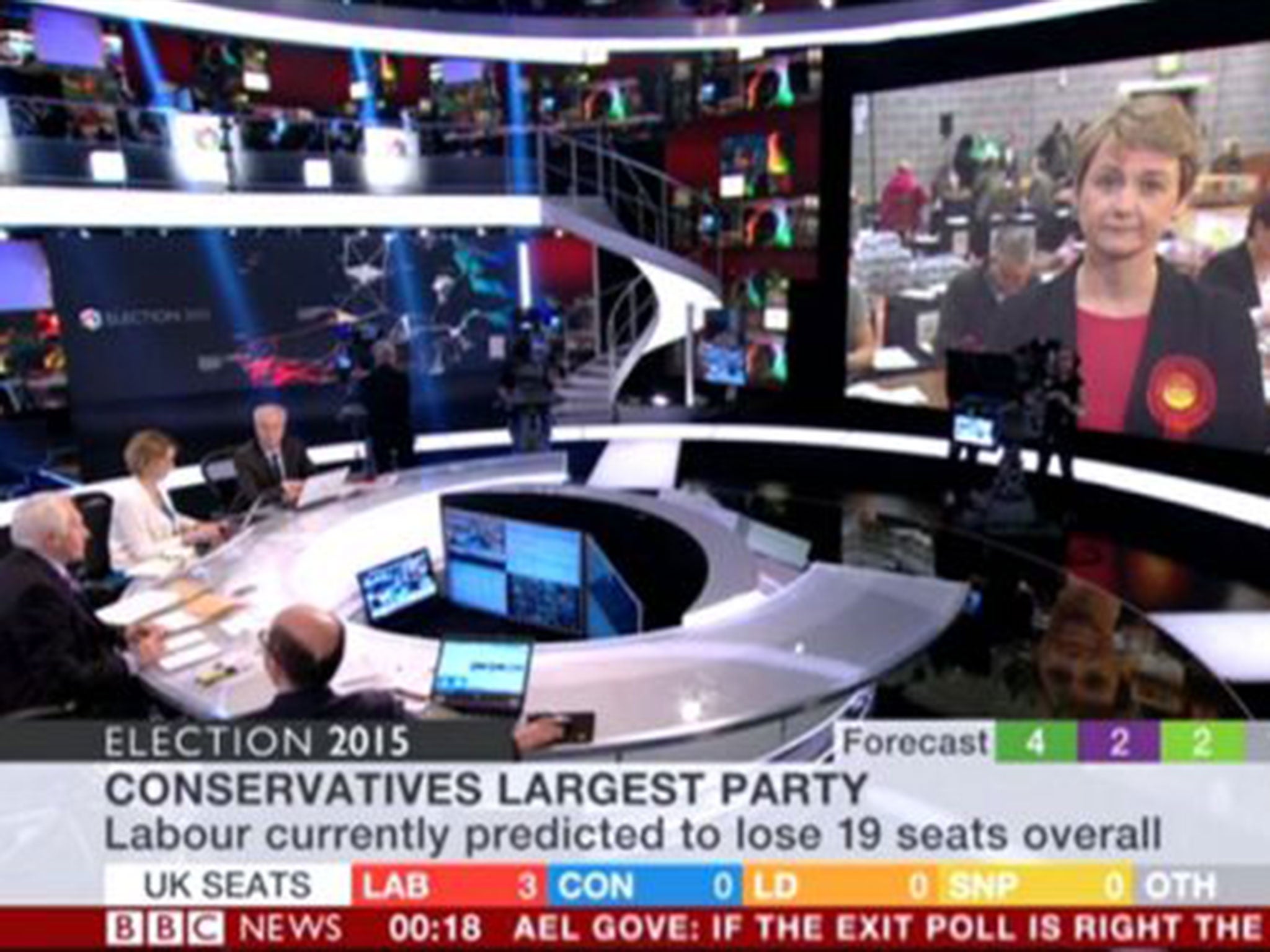

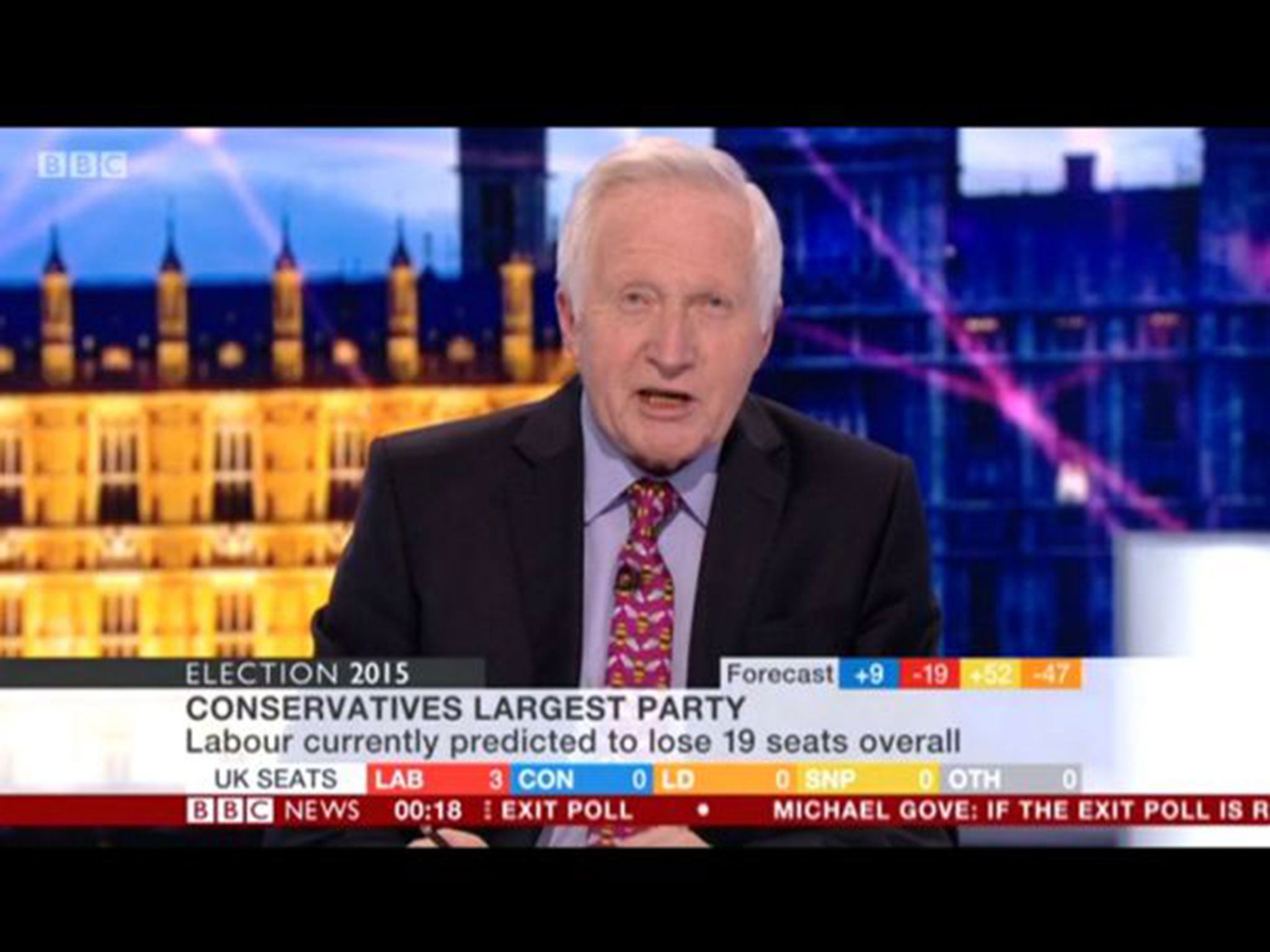

Leaving aside the pundit-confounding result, with its echoes of 1992, by far the greatest twitch on the ancestral thread was administered by the BBC. ITV may have had Bradby – pugnacious, knowledgeable and keen to keep his guests up to the mark – and a severe-seeming Julie Etchingham taking no nonsense at the battleground board; Sky may have roved so effortlessly around the constituencies as to make the chair-bound viewer feel slightly dizzy, but, in terms of overall impact and despite the usual whinging from the Daily Mail (‘ponderous’, ‘viewers complain’ etc), the corporation’s efforts could not be faulted. David Dimbleby, in particular, was simply superb – unflappable, debonair, one moment coyly avuncular, the next looking like the goblin king in the sub-Tolkien fantasy saga informed of the unexpected defeat of the forces of light, ever courteous, even when dealing with the wittering unfortunates of the Opposition front bench, and at times winningly pedantic. There was a wonderful moment in which someone mentioned “Lady Sylvia Hermon’s victory in North Down”. Surely, Dimbleby interjected, as she was the widow of Sir Jack Hermon, shouldn’t that be plain “Lady Hermon”? The great snob diarist James Lees-Milne couldn’t have put it better.

Only once did Dimbleby’s suavity seem to desert him. This happened at 4am when, as the camera winged back unexpectedly from a news bulletin, you distinctly heard him uttering the words “for God’s sake” to the hapless coffee lady who had photobombed him. But his general enthusiasm seemed to have communicated itself to the host of sidekicks who laboured in his slipstream. Andrew Neil foxily interrogated; Emily Maitlis wore so much lip-gloss that she gleamed under the lights; Laura Kuenssberg filed incriminating questions; and it was good to see Nick Robinson, recovered from his illness but still a touch croaky, returned to the commentator’s chair. On the other hand, one didn’t necessarily go to the BBC to keep pace with events. As in 2010, they always seemed a fair way behind ITV – largely, you suspected, because the ITV roster included seats whose result was known but hadn’t yet formally declared. At 2.05am, for example, the BBC tally amounted to 17 and ITN’s 24, a gap that an hour later had widened to 88 and 103.

By about 4am, consequently, a modus operandi was in place: Dimbleby & Co for authoritative comment; the others for breaking news. Not, it has to be said, that the BBC’s outside broadcast lacked drama. “Let’s see if we can follow that ballot box there” Fiona Bruce zealously intoned as she arrived at the count at Sunderland, while the car carrying the Prime Minister through the Oxfordshire back lanes to Witney was trailed for so long that we might have been watching an episode of Road Cops. Clearly a lot of money was spent, – much of it, you imagined, by Sky – but, to the corporation’s credit, the 2010 celebrity river party was not reconvened. In fact, bona fide celebs were agreeably scarce, while those that did make it into ITN’s “opinion room” – Queen guitarist Brian May, for example – were usually worth attending to.

Naturally, cliché abounded. Ukip’s “2020 strategy” wound its way through the proceedings like knotweed through a lawn, and the number of times we were invited to respect the wishes of the electorate very nearly exceeded the total of Scottish Nationalist MPs. With cliché came an air of déjà vu, a sense of the same politicians sprinting from one studio to another, or, certainly until around 2am the same desperately upbeat message about not believing the exit polls and the chance of regional variations – doubtless communicated by mass text from party HQ – unconvincingly recited by a procession of Labour MPs.

As for those moments of human drama, you were struck by just how infallibly polite were the vast majority of campaigners. Had it been in my power I would have returned Jim Murphy and Douglas Alexander their seats merely for the lack of rancour with which they accepted their defeat.

Meanwhile, the long, tumultuous night was coming to an end. Dimbleby, who seemed to have enjoyed himself tremendously, departed the BBC, still twinkly-eyed, for bed. The others carried indefatigably on. It was the Conservatives’ night – beyond Scotland, that is – but also the BBC’s which, it might be said, does these affairs better than anyone else. If Friday’s long, unfolding tableau showed us a deeply divided nation, then it also offered us the salvation – at any rate in media terms – of a single, unifying force.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments