The truth about Black, Caribbean carnivals like Notting Hill and Spicemas

Despite the colourful costumes, body positivity, food and fun, Caribbean carnivals were born in response to Black trauma, writes Nadine White. They are celebrations of hard-won liberation and we should protect them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Another year, another Notting Hill Carnival. Front page photographs of men and women in flamboyant costumes. Pumping music, dancing revellers. Then the inevitable trickle of negative news coverage.

But that’s not the carnival I know. This year I decided to celebrate carnival in one of the places where it all began: in the Caribbean, where there’s no better reminder that annual events like the Notting Hill Carnival have their roots in Black resistance, and where deep joy is the order of the day.

Welcome to ‘Spicemas’ in Grenada, and the true spirit of Caribbean carnival.

I was there at the invitation of Industry 360 and the Grenada Tourism Authority, and during my week-long stay on the island, had the pleasure of experiencing the nation’s flagship fete. I found myself “playing mas” (short for masquerade) for the first time.

Even though I was on the other side of the world, experiencing one of the world’s longest-running carnivals made me consider the parallels between it and Notting Hill Carnival back home in London.

That both events are emblematic of aversion to racist oppression rests heavily on my heart, particularly as a Black-British Jamaican woman of Nigerian heritage and Britain’s first dedicated Race Correspondent.

Jab Jab

Each day in Grenada, a group of us boarded our minibus at the Sandals Resort where we were based, to attend various events that form part of Spicemas celebrations – from Calypso Monarch to Waggy T’s All-Inclusive Fete and Pretty Mas (shout out to Nirvana Empire band for my costume).

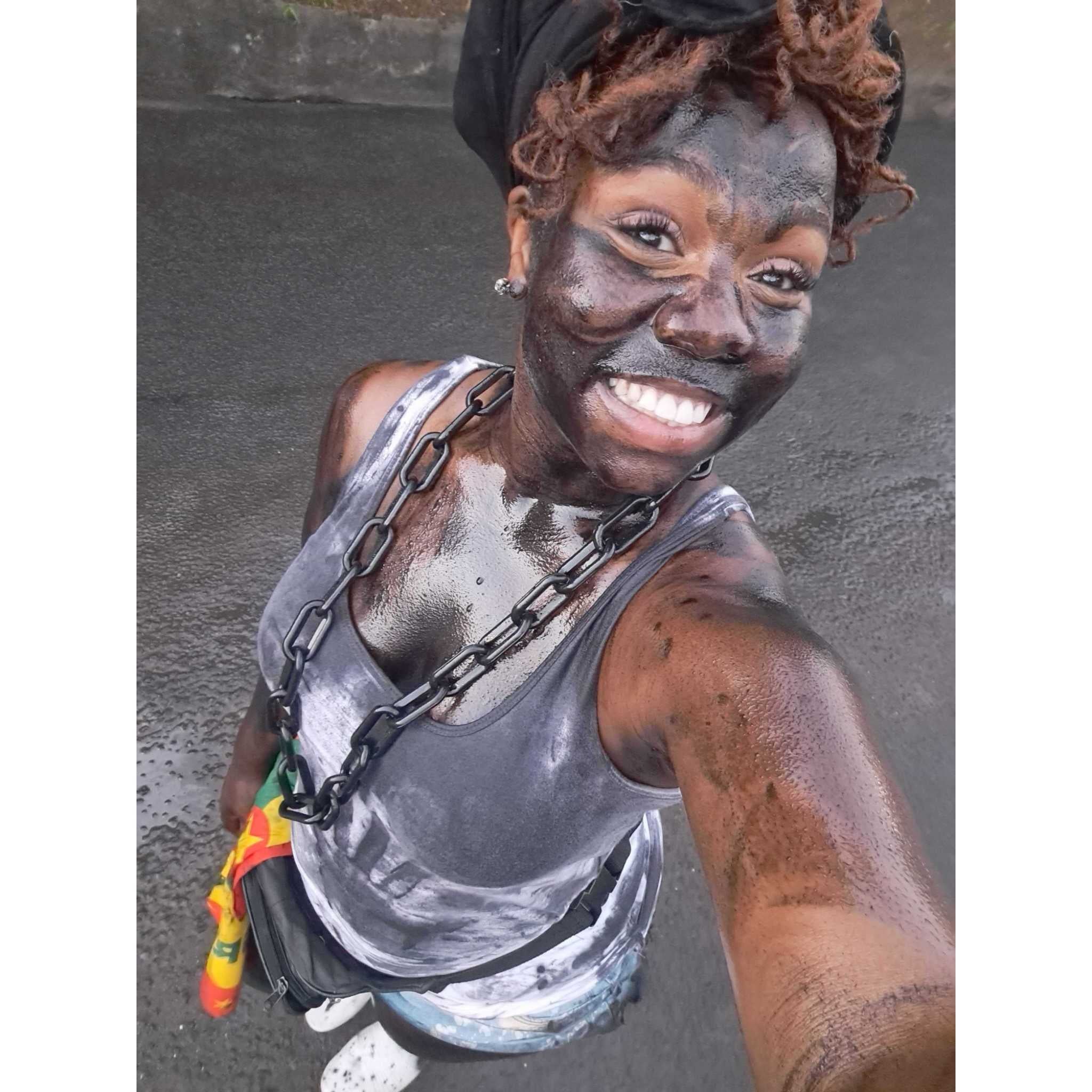

But it was Jab Jab or “J’Ouvert” that had a particularly profound impact on me – a traditional, satirical masquerade dating back to 18th-century plantation life during the days of slavery. (The word ‘Jab’ is derived from the French colloquial word “Diable” meaning “devil”, so a masquerader playing ‘Jab Jab’ is playing the devil.)

Back then, enslaved African people would join in this activity as their white enslavers looked on, oblivious that it was them – the enslavers – who were being mocked in plain sight! An ode to the ancestors’ ingenuity, strength and courage in the face of danger.

The parade was (and is) a satirical take on “massa”; to play “Jab” is to mock the forces who, for centuries, denied Black ancestors their liberty.

In present-day Grenada, practically everyone who participates in “Jab” is entirely black to the naked eye with skin coated in oil. Back in slavery days, they’d use molasses too.

It’s a double entendre; satire, yes, but also a unifying display of Blackness, as Grenadians told me.

Nowadays, revellers also sport horned helmets, reflecting the souls of the ghoulish enslavers and bear – not wear – chains symbolising the shackles used to subjugate Africans, in celebration of hard-won liberation.

So, I exited an all-white soca concert at about 4 am on Monday 14 August, with a classic crew of creatives and writers from the diaspora to get ready for J’Ouvert morning.

In keeping with Grenadian tradition, we adorned our bodies in grease that glistened under the dusky morning dew in a stark, righteous contrast to the snow-coloured ensembles we’d worn hours before.

There was a soft irony there; ebony and ivory, white and black.

I looked over the balcony in St George’s, the nation’s capital, and saw folks beginning to take to the street in the early hours in anticipation of what was to come.

Few people reached indoors before lunchtime. It was a long morning, especially for those who lacked stamina!

“Cryin’ in the club”

Jab challenged me, man. Marching along to the rhythmic thumps of Grenada’s Jab music, I stumbled backwards a few times, taken aback and slightly dazed under the sun’s hot gaze.

Some fellow attendees, in full character, were chewing something that seemed to be dripping with a blood-like substance to my left and coffin effigies were being dragged to my right.

It isn’t for the faint of heart and it is not supposed to be.

The bold display is meant to be striking, even offensive to so-called polite society. If you are moved, even a bit shook, then all the better.

J’Ouvert celebrations also take place in Notting Hill Carnival, where attendees rise and hit the streets early doors for similar activities. Caribbean cultures, like all others, transcend borders.

However in Grenada, home to former plantations, the legacy of chattel slavery is almost tangible, so Jab slaps differently.

Aftermath

Having arrived back at my hotel room after the event, I closed the door, sat alone in silence before deeply exhaling and blinking away tears.

Why was I crying? I wasn’t unhappy in the slightest. But the experience of something that genuine and that raw connected very deeply with me. Was it ancestral energy? I could not tell you. I was quieter than usual for three days straight, until I boarded the plane for Gatwick, as I sat with what I’d witnessed.

I didn’t rush to write this article either because it felt important that the experience marinated for a bit, while I reconciled with the trip and found my words.

Upon reflection, it has dawned on me that Jab confronted and disrupted my sensibilities as a guest to this aspect of Caribbean culture.

The unfamiliar pang I felt was, in fact, my awakening to a live embodiment of the potent and prepossessing procession of Black people – mostly descendants of the enslaved – victoriously bearing up their cultural tradition in a way that I’ve never seen before.

To me, it was new and radical. The centring of Black joy and pride. Yet, seeing Black Caribbean people galvanise from a place of pain felt familiar too. After all, that is what many of us, through sheer necessity, have had to do since, well, the interruption of slavery.

Some outsiders and keyboard-warriors on Twitter/X seem quick to denounce Jab, with all its outlandish aesthetics, as “witchcraft” apparently leaning into a trend of broadly maligning African traditions, in a fashion that is straight from the colonisers’ handbook.

Quintessentially Black and West Indian

Still, those who hold the custom dear and are familiar with its origins, say it is the ultimate ode to sweet and poignant revolution. Quintessentially Black and West Indian.

Boarding my flight for England, I chatted to fellow writer Nicholas Tyrell-Scott about how the trip has strengthened my resolve to be protective of all Caribbean cultures – and our people’s innate right to proudly partake in it.

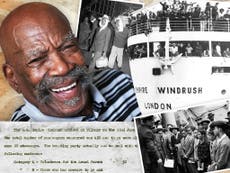

So, you’ll understand that returning home to see the routine ridiculing of the UK’s Notting Hill Carnival – a Black British-Caribbean institution founded by Windrush trailblazers, including giants Claudia Jones and Rhaune Laslett – has been particularly difficult to stomach this time around.

Carnival’s crime narrative persists, despite the myth being dispelled time again, and swathes of Black Britons are villified by association.

The common misconception is that, where two or more Black people are gathered, trouble is bound to take place - smacking of old colonial rules that forbade enslaved Africans from gathering without a white slavemaster present.

Many people who are, at best, outsiders to Caribbean social heritage, sneer at important cultural customs that take place at the event. This should inspire those of us who care about it to call it out and protect this valuable event.

Britain owes so much to Caribbean people – from the carnival itself, which pumps millions of pounds into the country’s economy, to the formation of key elements of the country’s infrastructure, like the NHS.

Rhythm and blues

I had never before participated in a carnival; neither Notting Hill nor Jankonoo in my family’s native Jamaica, or any other iterations. I’ve merely admired while bubbling on the outskirts.

As a first-timer, my participation in Spicemas shifted my perspective.

This past month has reminded me that even though the rhythm underpins Caribbean carnivals, so too does the blues.

The unsolved, racist killing of Kelso Cochrane, an Antiguan 32-year-old man whose death in 1959 sparked race riots and inspired London’s Carnival as a unifying affair.

Then there’s Spicemas which stemmed from Black captivity. Today: leaders of the Caribbean’s 13 sovereign nations continue to lobby Britain for slavery reparations and an apology, while the West ignores this.

In an exclusive interview with me at his home, Grenada’s prime minister Dickon Mitchell said of Spicemas: “It’s a collective expression of our creativity. It’s also, in a sense, an opportunity for people to de-stress so that they actually can cope. The daily grind of life can take its toll...so there’s also that aspect of it."

Grenada has the highest poverty rate among countries in the Eastern Caribbean – it’s not hard to make the connection between chattel slavery, lack of compensation for Caribbean economies post-abolition and the present-day situation or “daily grind”.

Despite the colourful costumes, music, body positivity and fun, Spicemas and Notting Hill Carnival were both launched in response to Black trauma, and the struggle for equality persists.

Emancipated we are – but not in every sense of the word. When justice is delayed for people of African descent – such as in the case of Kelso Cochrane and descendants of enslaved African people – then justice is being denied.

In the meantime, through events like these carnivals, the tide of resistance rages on and it says "we are here, we matter".

This is why, far from just being a big party for all and sundry to attend, these events are so crucial and deserving of the utmost respect.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments