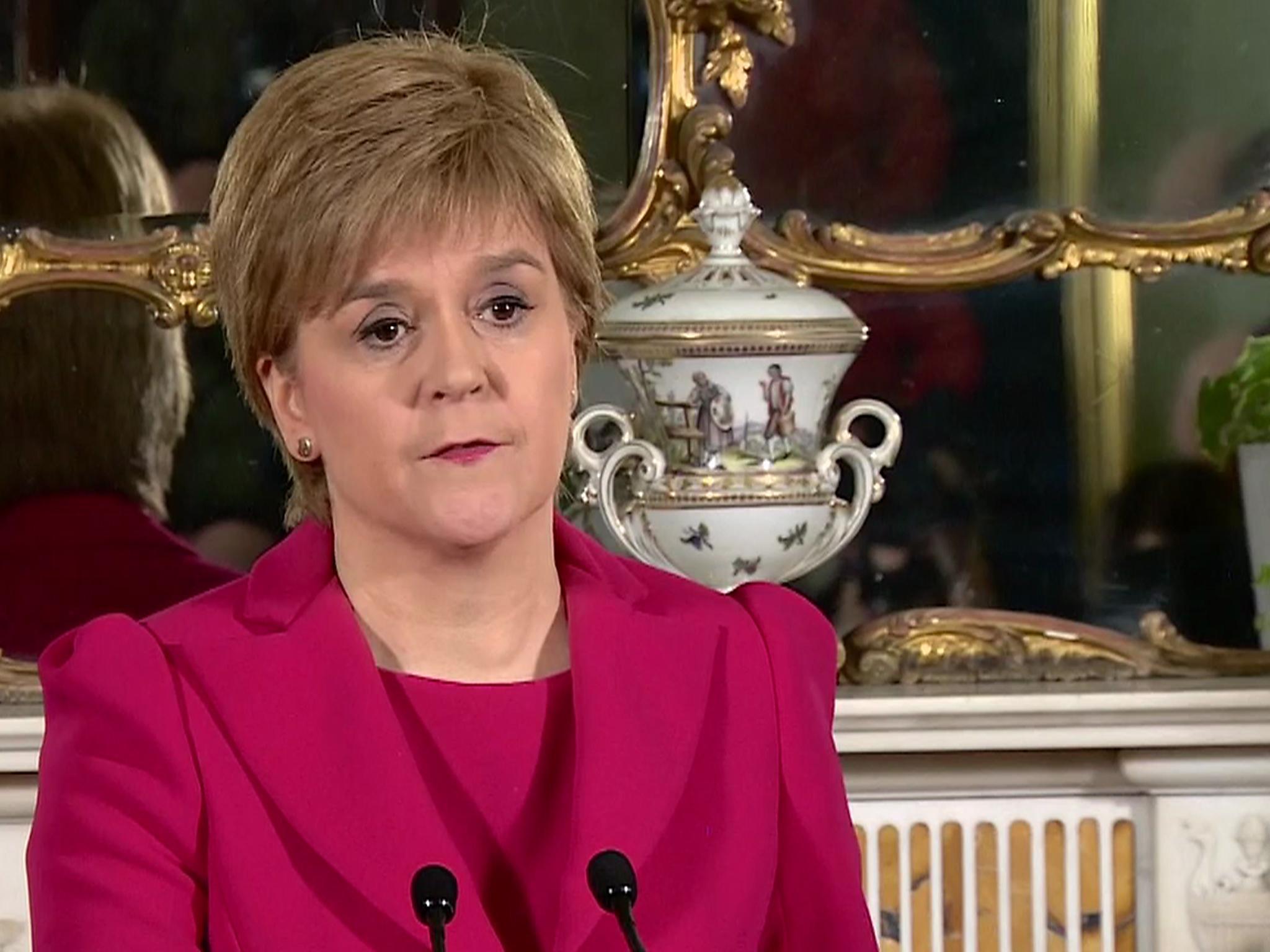

Nicola Sturgeon has thrown down the gauntlet – but who would dare to stand against her in the next Scottish referendum?

The Scottish Labour and Scottish Conservative parties have made much in recent months about resisting another referendum, but such a strategy is now subject to the law of diminishing returns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s often been said that Nicola Sturgeon is more cautious than her predecessor Alex Salmond, but she has taken a huge political gamble, one that’s incredibly risky not only for her, but also the SNP and the wider independence movement.

Risky because not only do opinion polls not show a decisive majority for independence, but because the economic case for independence – so important during the first referendum – is now much weaker. The First Minister says she wants the second ballot to be “fact based”, but many of those facts are presently much less helpful than they were a few years ago.

Polling also suggests a majority of Scots don’t want another referendum so soon after the first, although given it’s now all but inevitable, that’s probably academic. Within the next two years, they’ll most likely vote once more on the question that provoked such wide-ranging debate between 2012 and 2014.

The Scottish Labour and Scottish Conservative parties have made much in recent months about resisting another referendum, but such a strategy is now subject to the law of diminishing returns. The SNP, of course, will argue they’ve been left with little choice given the Prime Minister’s refusal to countenance a “differentiated” deal for Scotland after triggering Article 50.

Scottish Greens, meanwhile, say they’ll support Nicola Sturgeon’s call for a fresh Section 30 order when it comes before Holyrood at some point next week, which would enable her to hold another referendum. This is important, for it means the Scottish Parliament has a pro-independence majority, and it’s there that this process will now unfold over the next few weeks.

The First Minister says her preference is for a vote between the autumn of 2018 and spring of 2019, although that seems likely to be up for negotiation, as it (the timing) was when the Scottish and UK governments reached agreement over the terms of the first referendum back in 2012. It’ll be hard for Theresa May to say an unequivocal “No”, so she’s likely to say “Yes, but”. There will be caveats, but the SNP is prepared for that.

What of the likely shape of the Yes and No campaigns? Both seem likely to be fundamentally different to the “Yes Scotland” and “Better Together” organisations that dominated the first referendum. During her announcement, Sturgeon said “we will be frank about the challenges we face”, which suggests a more realistic pitch about both the risks and opportunities presented by independence. How “frank” she’s willing to be, however, is yet to be seen.

And for Unionists, there won’t be another umbrella campaign, not least because Labour was badly damaged by its previous association with the Tories, who remain toxic for many Scots. So, the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats will each fight their own distinctive campaigns, which will allow a variety of Unionist “visions” but which also risks looking fragmented and contradictory.

While Nicola Sturgeon, who’s still popular and respected, will undoubtedly lead the independence fight, it’s not altogether clear who’ll head up the No campaign. Ruth Davidson, the similarly charismatic leader of the Scottish Conservatives, has said she won’t, rightly fearing an SNP-on-Tory battle would undermine the Unionist case. But that begs the question: who else is there?

Unless the likes of J K Rowling are prepared to step up to the plate then it isn’t entirely clear. And the Unionist challenge extends well beyond personnel, for in this post-Brexit and post-Trump political world, making arguments based on empirical fact and spreadsheets is no longer enough, voters need to feel their “identity” is being represented by those arguing for one outcome or the other.

Such a role naturally suits the Yes side much more than the No. And whatever drawbacks there are in terms of economics, oil and all the rest, the SNP’s is a well-oiled political machine that positively relishes election and referendum campaigns. There’ll already be a “grid” in place, and Nicola Sturgeon’s surprise announcement at Bute House is simply the first of many squares.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments