Emotional, desperate, full of rage – why I joined the Paris protests with my teenage daughter

Sophia came to the French capital to celebrate her 18th birthday – instead, we were caught up in carnage in the suburbs, writes Amelia Loulli. Neither of us will forget what we witnessed

This trip to Paris with my teenage daughter, to celebrate her 18th birthday, has been filled with all of the things you might expect. Long walks through the city past endless iconic landmarks, slow brunches filled with deliciously delicate pastries, warm chocolate crepes, baked eggs.

We’ve hung out in literary haunts made famous by the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, we’ve walked through the gardens of Renoir, climbed the incredible metal legs of the Eifel Tower and sailed along the Seine at sunset, taking in views of the Notre Dame Cathedral and the Pont Nerf Bridge.

But all of this regular luxury has been juxtaposed with the terrible news roaring through Paris of the tragic death of Nahel M – the 17-year-old shot dead by police during a traffic stop in Nanterre on Tuesday night.

As we watched the Eiffel Tower light up like a giant sparkler every hour on the hour of our second night in the City of Lights, riots broke out in an area just 20 minutes by train to the west of the centre of the usual, familiar tourist buzz.

As a mother of teenagers – I have three – it felt impossible not to go and add our voices and our support. I talked to my daughter about it and she wanted to be there. To shout with them. To state the obvious: that nobody should ever need protecting from the police. We’ve seen it in the UK too many times, particularly with women. We are all angry. It is time to speak out.

It also felt significantly clear that Nahel’s mother needed support from other mothers. I would want that too, if it were my child. It felt awful to carry on blithely eating croissants and doing nothing.

So, we find ourselves in Nanterre. The streets are restless. There is a strange, tense mood, like heavy weather that is about to break. The wide open stretch of children’s play parks and benches that are spread like squares on a chess board between the colourful apartment blocks and the Courts of Justice leading from the Place Nelson Mandela, are deserted.

Parents take their children by the hand and walk them home at lunchtime from the school blocks at the end of the road, which is completely cordoned off by an overwhelming presence of police vehicles – 30 to 40 vans – and officers holding riot shields.

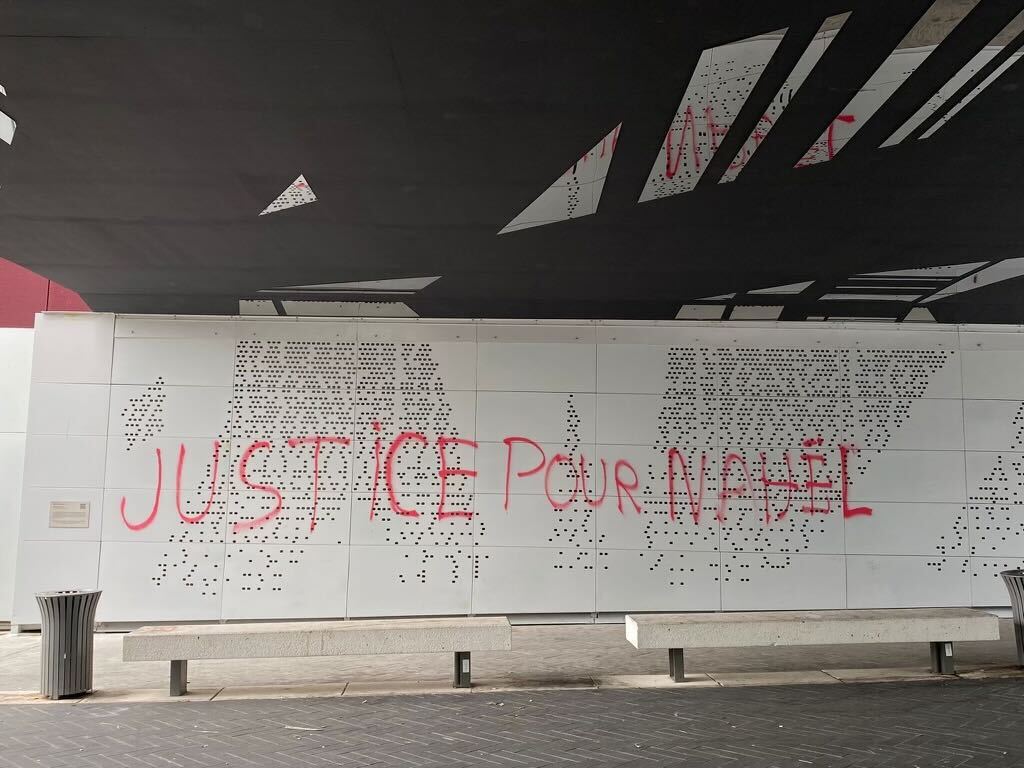

There is an undeniable atmosphere of “us vs them”, as the police – assembled in force, dressed in full protective gear – prevent free access to the streets and roads, many of them eating lunch on trays in their police vans. Under a bridge joining university buildings to family apartment blocks and shops, the words “Justice pour Nahel” are written in red paint.

Or, they were. Within an hour the words are scrubbed off. For a while, the only noise is the sharp sound of sirens which fill the place like a dreadful moan.

If the sirens could speak, wouldn’t we hope they would say “we’re sorry”, “we mourn too”? But this was not the feeling we got. The overwhelming feeling was one of aggression, of no remorse, of power above all else.

The police are here. They are very, very here. And they want the people to know it. A crowd of people and reporters begin to gather at the gates of the courts. The people are eerily quiet. That is, until the protest, which forms at Avenue Pablo Picasso, begins.

Quickly gathering huge numbers, it is charged with a painful desperation and the powerful, guttural screams from thousands of people, repeating the red words from under the bridge: “Justice Pour Nahel”.

It’s impossible not to cry out along with the crowd as we follow the van carrying Nahel’s family and friends, holding their placards bearing their beloved’s name. We walk with them, clapping and chanting. It’s all so impossibly unlike the centre of Paris just 11km away.

As a mother, here with my daughter Sophia, the same age Nahel was, I wonder if he ever climbed the Eifel Tower, if he liked baked eggs – what he wanted to do with his life.

While we are here, my daughter receives a phone call confirming her place on the college course she hoped to get on for next year. Her life, like all teenagers is, or should be, hers for the taking. And yet here we are, walking with thousands of people who know this is not always how it plays out.

We are no longer strolling along the banks of the Seine, instead we are witnessing and taking part in something vital: a call for something so basic, so fundamental, it feels impossible that it must be called for at all. The call is for justice.

There are signs listing the many names of other people killed by police in France. The rage of the young people and the communities of people of colour here in Nantelle is painfully palpable.

How can anyone have hope in a world where the lives of young people are taken so brutally away for no reason whatsoever? There is an intensely fierce desire here, as in so many places, for fairness, for protection of all of our children.

People scream “deteste la police” and hold signs which say “protect us from the police”. I hold my daughter’s hand as I walk, watching Nahel’s mother atop the roof of the white transit van as she cries for a justice that we all know won’t bring her boy back.

I shout for justice for Nahel with everyone here in Nanterre, knowing that none of our children are truly protected until they all are.

As the protest progresses through the intense Parisian June heat, it blocks every road approaching the courts.

Suddenly, the people, clapping, cheering and chanting feel like no match whatsoever for that line of police vehicles. We all roar in support as we watch Nahel’s mum, Mounia, stand on the roof of the van outside the courts, holding a flaming flare in her hand.

The police look on in solid block formations from behind the spiked fences; the mood changes to one of extreme tension. I remember that while we sailed the Seine last night, my daughter and I watched a police speedboat full of laughing officers tear carelessly down the river like a bullet.

Then, as now, my daughter asked quietly why they were behaving like that – then answered her own question: “Because they can, I guess.”

And then the officers fire tear gas into the crowds. The sky fills with smoke, people start wiping their eyes with their T-shirts and I leave Nanterre with stinging eyes, for my own child’s safety, knowing that we are so incredibly fortunate. Knowing that others are not. Knowing that the cries of “Justice Pour Nahel” will echo in my ears long after we are gone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments