The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Monkeypox isn’t ‘Black’ or ‘gay’ – it’s global

Media representations of illness breed stigma and influence our perceptions of the risk to ourselves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s been over 100 years since the Spanish Flu outbreak swept across the world. It is a disease that has become synonymous with the Covid-19 pandemic, a cautionary tale of the destruction a flu virus can have on a global population. But did you know it is not actually Spanish? That the disease itself likely did not originate in Spain?

Instead, it is named the “Spanish” flu because the Spanish media reported on this new and deadly disease, whilst other countries, beaten down by the First World War and wanting to keep morale up, simply did not.

Understandably, Spain was none too happy about being saddled with “ownership” of the killer virus, preferring to pass the buck, locally calling the H1N1 influenza strain the “French flu” and the “Soldier of Naples.” But the name stuck, all because the media at the time had hit on an “easy” shorthand for a complicated disease.

It may make sense to use these simple shorthands when reporting disease outbreak, but they are not without consequences which have played out over our history. Fast forward to the 1980s and the emergence of HIV. Originally referred to as GRID, Gay-Related ImmunoDeficiency, by both the media and the medical community, the etymology of the disease did two historically important things: first, it stigmatised an already stigmatised population by labelling them as the carriers and vectors of a deadly disease.

Second, it sent the dangerous message that this was something that only impacted a select group of people – if you weren’t gay, you didn’t need to worry about this disease. Today we know that message cost lives, as homophobia and discrimination, fuelled by the labelling of HIV and AIDS as a “gay” disease, continues to put gay and bisexual men at higher risk of infection and death than any other at-risk population to the disease.

The role of the media in solidifying the origin of a disease is an important one. All the major disease incidents in the years that have followed the 1918 Influenza pandemic have been simplified down to target the country or proposed carrier of the disease.

Think about “Bird” and “Swine” flu. Even the now famous Exercise Cygnus used the fictional “Swan” flu to test the UK’s pandemic-preparedness. The current pandemic has been no different, with media reports initially labelling Covid-19 the “Chinese” and “Wuhan” virus and attributing nationality to variants. Each of these labels, perpetuated by certain sections of the media, has been linked back to discrimination for the groups “named.”

But we’re woke now, right? Modern media would never call something a “gay” disease. Newspapers don’t go around casually attributing neutral viruses to countries or populations of origin. We know better now; we’ve learnt from our mistakes. Or have we?

Which brings me to monkeypox. Despite calls during the pandemic to end the practice, this hasn’t stopped certain sections of the media from zeroing in and labelling this a “Black,” “gay” disease. Portrayals of monkeypox in this way have been so prevalent in global media reporting that it prompted both the Foreign Press Association, Africa and the UN programme on HIV/AIDS to issue statements urging the media to step away from stereotypes in their reporting, including using stock images of black skin with monkeypox and images of gay men. To consider the harm they cause by perpetuating discriminatory stereotypes.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

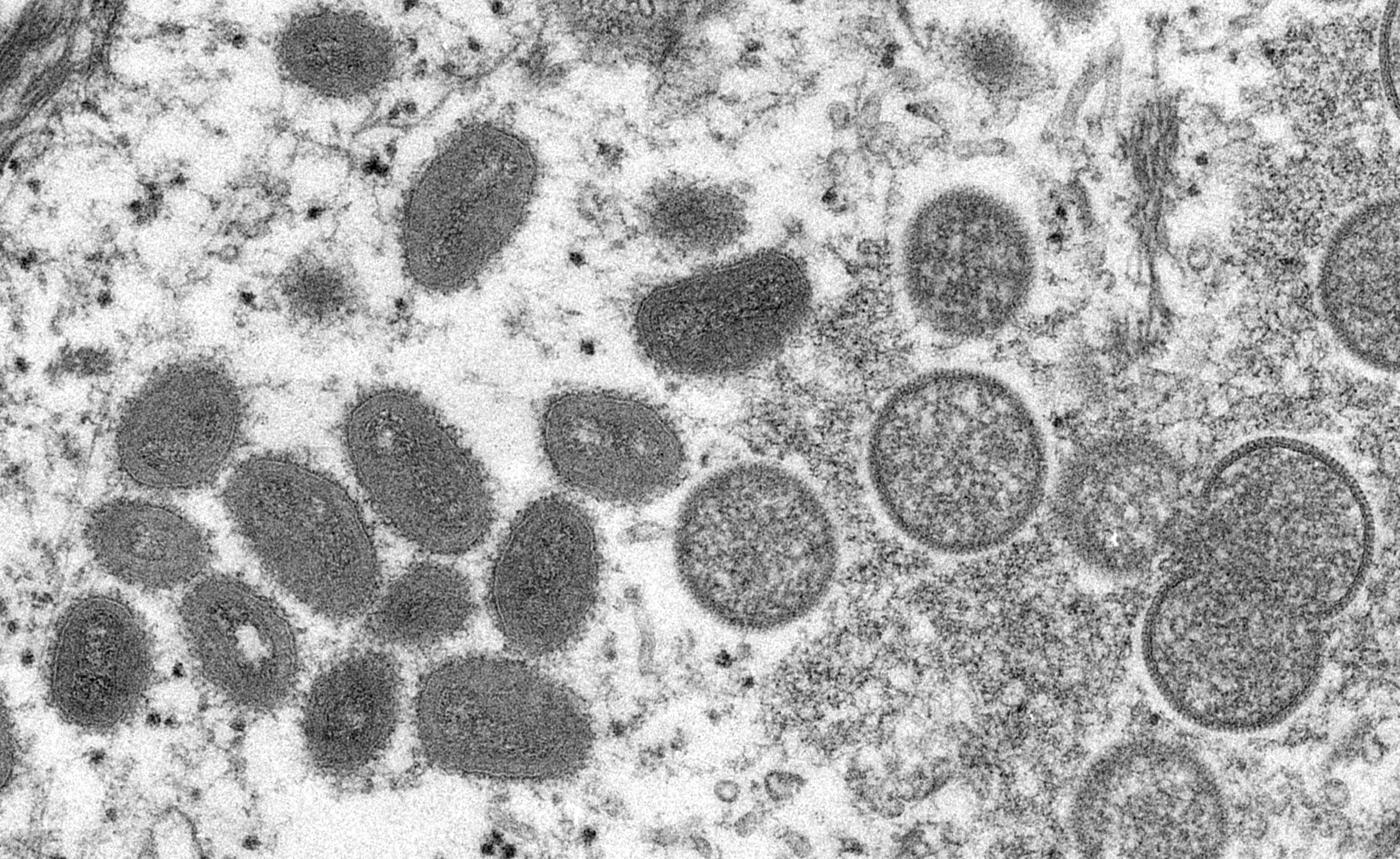

Whilst some may argue that stock images from Africa are all global media have to use, this seems a bit lazy to me. What about images of a generic virus to accompany news articles on monkeypox?

Every news agency across the world has enough of those alien planet artist renderings in psychedelic colours to last them a lifetime of news reporting. If that doesn’t suit, the UK media is no stranger to posting a photo of an NHS hospital trust sign when reporting on health events, and yet at no point has this been the go-to either. Or, call me crazy here, perhaps photos of actual patients here in Europe? (If they are willing, of course.)

Why does all of this matter? Because how the media reports and represents these outbreaks is not just about sloppy shorthands - research has shown us that media representations of illness breed stigma and influence our own perceptions of the risk to ourselves. Meaning there is a direct link between reporting styles and focus, and how much of a danger, we, the readers, understand ourselves to be in from others. We act on this perception of risk to protect ourselves, resulting in discrimination of, and sometimes harm to, innocent people to abate our fears and satisfy ourselves we are safe.

Monkeypox is only the next in a long line of disease outbreaks that our planet will weather. The media has a duty in promoting disease as global, abandoning the need for origin, viewing the people unfortunate enough to discover or catch the disease as victims, not nameless vectors to name, shame and blame for disease spread. Viruses are not racist and homophobic: people are, and it is time certain sections of the media stepped up and report disease outbreak without prejudice too.

Dr Alexis Paton is a lecturer in social epidemiology and the sociology of health and co-director of the Centre for Health and Society at Aston University. Dr Paton is also chair of the Committee on Ethical Issues in Medicine at the Royal College of Physicians and a trustee of the Institute of Medical Ethics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments