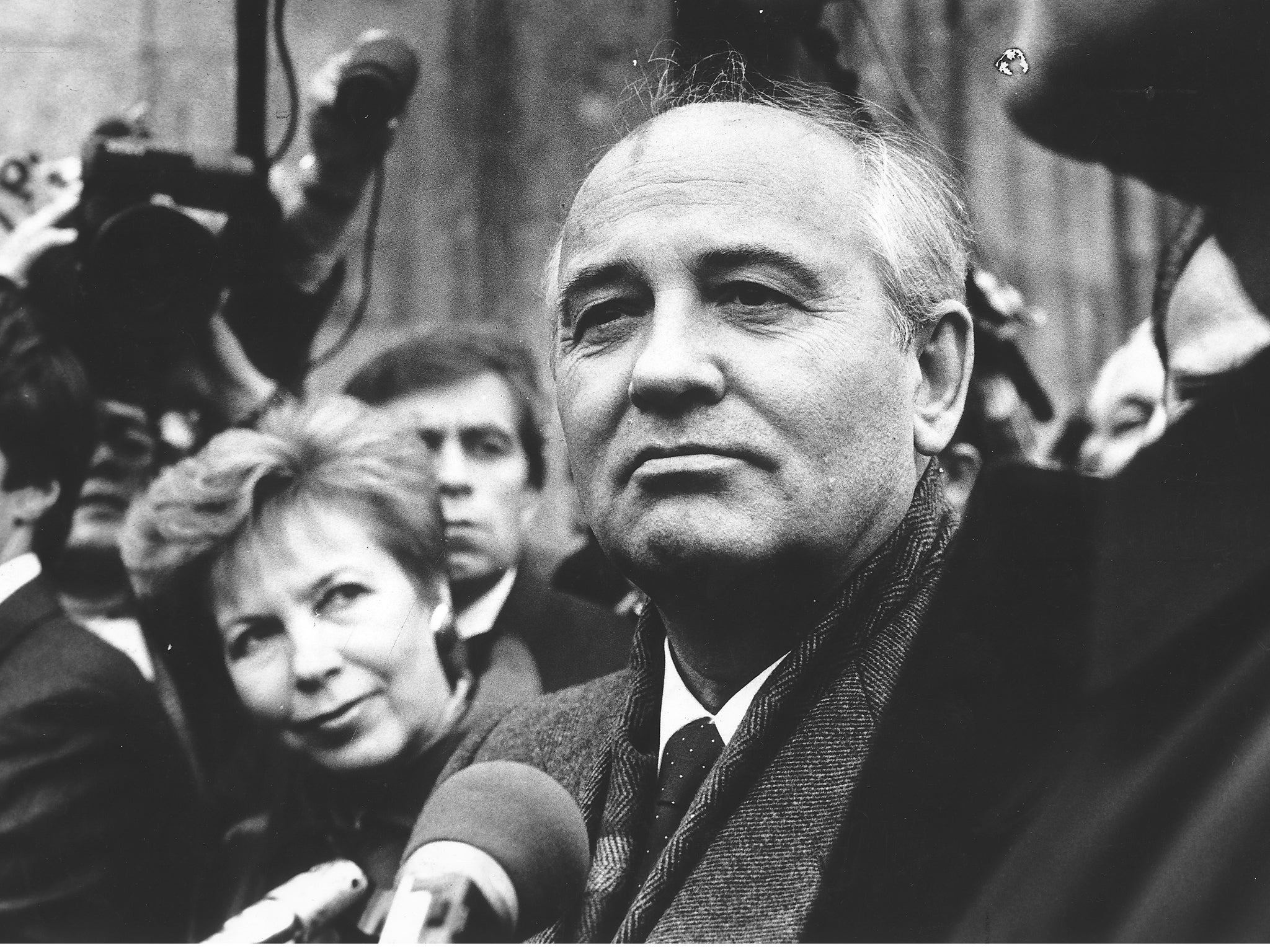

Mikhail Gorbachev was a hero of our time

Former foreign secretary Malcolm Rifkind pays tribute to a great statesman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mikhail Gorbachev was a hero of our time. There is no exaggeration in this assessment. Through his leadership, the Cold War came to an end, the Berlin Wall was demolished, the Warsaw Pact was dissolved, and Poland, Czechoslovakia and the other captive nations of eastern Europe became free and able to control their own destiny.

Throughout these extraordinary events, not one shot was fired, and not one Soviet soldier intervened to prevent them from happening. Contrast that with the invasion of Hungary in 1956 and the Soviet suppression of the Prague spring in 1968, not to mention the gulags, the purges and the brutality of Stalin and his henchmen.

I met Gorbachev at Chequers when he visited Margaret Thatcher for the first time in 1984. At that time, neither he nor anyone else believed that the Soviet Union would cease to exist seven years later. He was anxious to reform the system – not to destroy it.

But he knew that it would need genuine reform, and the result was glasnost and perestroika – openness and reconstruction.

At that meeting at Chequers, we could see that Gorbachev was very different from Brezhnev, from Andropov and other Soviet leaders. Both he and his wife Raisa represented a whole new generation of younger communists who knew that the Soviet system was approaching breaking point.

While Gorbachev had his tete-a-tete with Margaret Thatcher, I was taking Raisa Gorbachev around the library at Chequers. As she examined the volumes, she remarked that she was delighted to be in England; that she had always wanted to be in the country of Hobbes and Locke. She talked of the 20th-century English literature that she and her husband were familiar with. This couple were very different from the Communist Party bosses we had dealt with for years.

These talks that Gorbachev had with the Iron Lady did not lead to agreement. Gorbachev, at that time, remained a convinced communist. What Thatcher announced to the world was that Gorbachev was a man with whom we could do business. They not only liked and were stimulated by each other; they had concluded that they could each trust the other.

Ronald Reagan would have been unimpressed by any other Western leader praising the youngest member of the Politburo. But he accepted Thatcher’s judgement, and the rest, quite literally, is history.

But there is a paradox. While Gorbachev has been praised as an iconic figure in the West, in his native country he has been deeply unpopular, and was politically marginalised throughout the rest of his life.

Russians were as pleased as anyone to see the end of the Cold War; there has been little regret at the collapse of communism, and few object to the Poles, Hungarians, Czechs and Slovaks having been freed from Moscow’s control.

The end of the Soviet Union was another matter – not because it was Soviet, but because it was the Russian empire that had existed since the days of Peter the Great. One senior Russian has remarked that Russia is not Belgium. It must be an empire to exist. Another has commented that Britain had an empire. Russia was an empire.

Since 1991, Russia has shrunk to sit within borders that it has not had for 400 years. That was not the fault of the West, nor was it what Gorbachev intended. The peoples of Ukraine, the Baltics, the Caucasus and central Asia saw a window of opportunity to achieve national independence, and grasped it before it disappeared again.

But while that was never Gorbachev’s strategy, it was, at least in retrospect, inevitable once he sought to achieve communism with a human face. Soviet communist totalitarianism was the product of the life’s work of both Lenin and Stalin. It was not a Stalinist aberration – as Gorbachev desperately wanted to believe.

The Russian people not only blamed Gorbachev for what they saw as Russia’s humiliation, in the years following 1991, by a mixture of Western hubris and opportunism. They also never forgave him for the chaos, unemployment, inflation and economic collapse of the transition years, as Russia was transformed from a command economy into a version of market capitalism.

Communism had not provided Western levels of prosperity, but it had given basic security to millions of low-income families and elderly pensioners, who saw their standard of living plunge when Gorbachev’s reforms led to consequences he had never intended.

It is said that prophets are never honoured in their own country. Nor were the profits of the oligarchs acceptable to the millions of Russians who did not share them.

Now, of course, we see, again, a different side of Russia. Six months of war in Ukraine have provided an unsavoury milestone at which to reflect on Vladimir Putin’s dominance – and aggression.

Putin’s popularity with the Russian people was not originally based on his foreign policy, nor was it due to his desire to restore Russian strength and control over its “near abroad”. Rather, it was because a combination of economic stabilisation, high oil and gas prices, and an emerging, competent business community after 2000 stopped the rot and led to real improvements in the standard of living of average Russians.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

No one, however, can take away from Gorbachev the fact that he, more than Reagan or any other Western leader, removed the ever-present danger of a global nuclear war that could have devastated the whole planet at any time during the latter years of the Cold War. It is a deep shame that Putin has raised those fears once more – though he is finding it difficult to prevail. His army is running out of spare parts, and he cannot afford to escalate this war to a nuclear level.

Tearing down the Berlin Wall, allowing the Baltic States to restore their independence, even ending the Cold War: all this could have been resisted in the traditional Soviet manner by tanks and troops. If that had happened, much of Europe would have witnessed the carnage, war and destruction that was the fate of Yugoslavia after Tito. We now see some of that aggression mirrored in Ukraine.

The West has followed America and Britain’s lead and rallied around Ukraine, supplying useful and advanced equipment. Nato has been revived and strengthened by the accession of Finland and Sweden – but we cannot forget the fact that now, at the time of Gorbachev’s death, there is a war of attrition in Ukraine, and many of the reforms that Gorbachev championed are being reversed.

Gorbachev made many mistakes, but he was on the right side of history. One day the Russian people will recognise that they have as much reason to be grateful to him as do the rest of us.

Sir Malcolm Rifkind was secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs from 1995 to 1997. As minister of state at the Foreign Office, he was present at Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit to Chequers in 1984.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments