There are now more middle class people in the world than poor – this offers great business opportunities, but poses political challenges

The new middle class may care more about a government that functions efficiently than about maintaining a democratic system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Something of enormous global significance is happening almost without notice. For the first time since agriculture-based civilisation began 10,000 years ago, the majority of humankind is no longer poor or vulnerable to falling into poverty.”

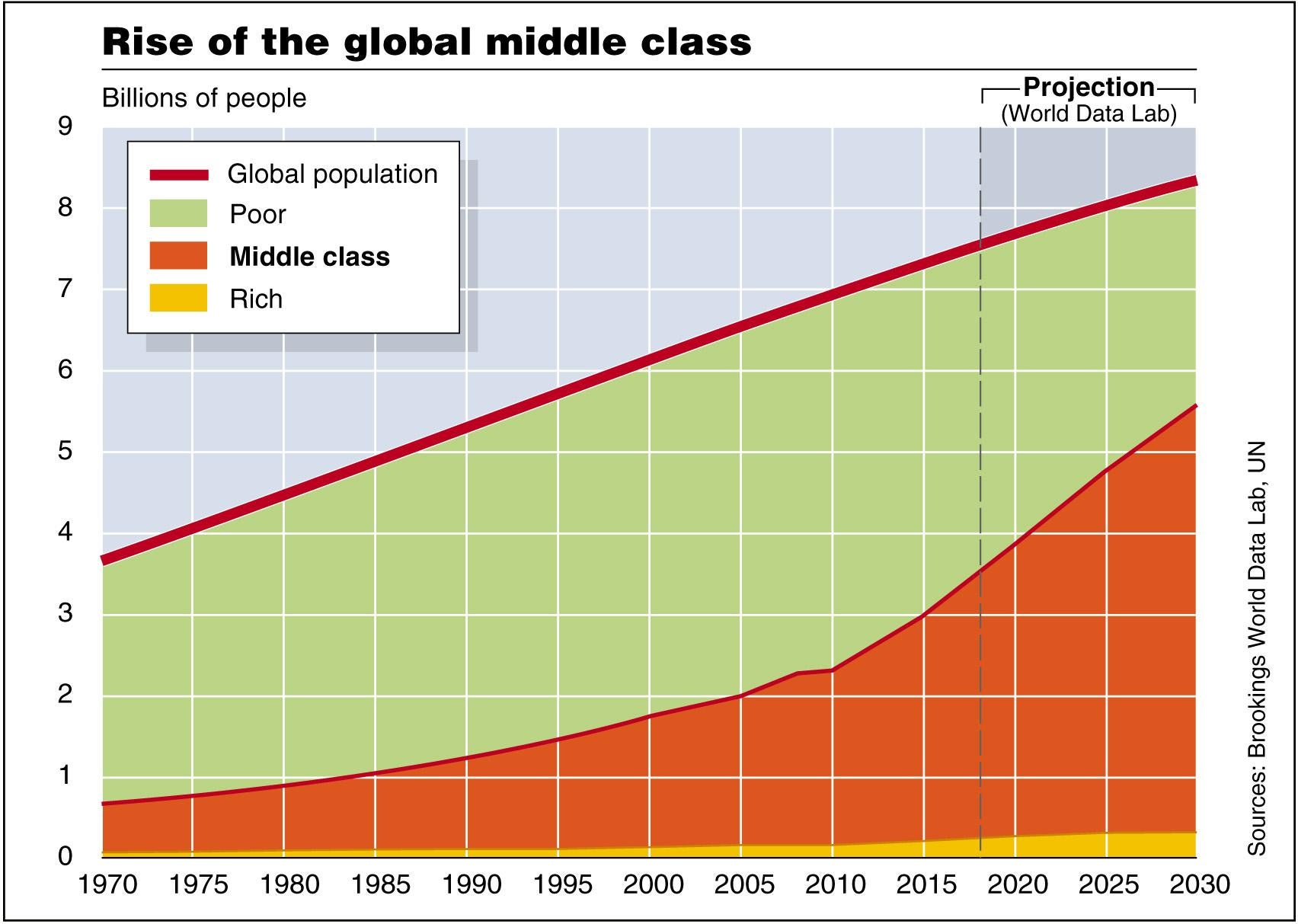

If that seems an extraordinary statement, well, it is – and a rather wonderful one too. I did not write that. It comes from a new paper published by the Brookings Institution, one of the most respected (arguably the most respected) research institutions in the US. The paper’s authors, Homi Kharas and Kristofer Hamel, have calculated that last month, September 2018, was the tipping point when the number of people in the world who were middle class or rich exceeded the number that were poor.

Before you challenge that statement for its spurious precision, a perfectly fair objection by the way, look at how the authors come to this conclusion. At the bottom end of the range, they take the OECD’s definition of middle class, established in a paper by Homi Kharas in 2010. For the bottom end of the range they take the official poverty levels in Italy and Portugal, two European countries that have the strictest definition of poverty. For the top end, the point where middle class people are classified as rich, they take double the median income level of the richest European country, Luxembourg.

You can quibble with the detail, and you could define poverty (or wealth) in other ways, but these are surely decent common sense benchmarks. A family would expect even at the bottom of the middle class band to have reasonable access to healthcare and education, and to have the funds to travel away from home, as well as the basics of food, clothing and shelter. They might not yet have a car, but they would have bicycles and mopeds. They would certainly have a mobile phone.

And to be rich, rather than just middle class? The median household disposable income in Luxembourg is around €6,000 a month, so on my quick tally that would mean a family of four in Britain would need a post-tax annual income of around £120,000, or pushing £200,000 pre-tax. That seems a reasonable number to be classified as rich.

The authors project their estimates forward to 2030, and these are shown, plus some UN data for earlier years that a colleague has pulled together, in the graph here.

Now think forward. At the moment there are 3.8 billion people who are either middle class or rich. By 2030 there will be 5.6 billion. In terms of spending power, the middle class of China and India will each be roughly the size same as the middle class of the US. There will still be many poor people in the world, some 2.3 billion that the authors classify as vulnerable and 450 million who are unquestionably poor. However they note that about one person escapes extreme poverty every second, while five people a second are entering the middle class.

What should we make of all this? From a business perspective there is obviously a huge market to be tapped. Creating products and services for the new middle class is a challenge and an opportunity. There is a fascinating question as to whether the new middle class will have similar tastes and values to the old middle class. Will the new rich? Will, so to speak, Crazy Rich Asians be the same as their counterparts in Europe and America?

What is a reasonable assumption, however, is that the ideas of Asia will affect the ideas of Europe and America, rather in the same way that the ideas of America now have transformed the way Europeans live now. Think Amazon, think Apple, think Google, think Facebook. Now imagine a world where the next big idea, the next Facebook, comes from India.

There are two further obvious issues raised by the rise of this global middle class. One is whether there is a danger that the vulnerable and the poor – wherever they are – will find they are bypassed. There will certainly be a rethink of the role of foreign aid. Is it effective and appropriate? What are the policies that have enabled so many people in Asia (and increasingly in Africa) to escape poverty? But might those policies, while benefiting the majority, make it harder for some people at the bottom of the pile?

The other issue is politics. The authors note that the new middle class will demand better government services:

“They look to their governments to provide affordable housing, education, and universal health care. They rely on public safety nets to help them in sickness, unemployment or old age. But they resist efforts of governments to impose taxes to pay the bills.”

Indeed. The question is whether people are more likely to be satisfied by democratic or autocratic systems. Or, to put the point slightly differently, maybe the thing most middle class people want from government is efficiency: good services at acceptable tax levels, and they are less interested in the political system that delivers this.

Actually the emerging world is better placed in one regard – its demography – than the old developed world. It is harder for an ageing Europe to maintain services simply because there are fewer people of working age to pay for those services, and more elderly people needing them. China will soon face this problem, but for India and the rest of south Asia, demographic pressures are at least one generation away.

But come back to the big point: the world is becoming middle class. I think that is wonderful. If you don’t agree, try this thought from Barack Obama. He has made this point several times in different places. This version comes from his final speech as president, in Athens in November 2016.

“If you had to choose a moment in history to be born, and you did not know ahead of time who you would be – you didn’t know whether you were going to be born into a wealthy family or a poor family, what country you’d be born, whether you were going to be a man or a woman – if you had to choose blindly what moment you’d want to be born you’d choose now. Because the world has never, collectively, been wealthier, better educated, healthier, less violent than it is today.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments