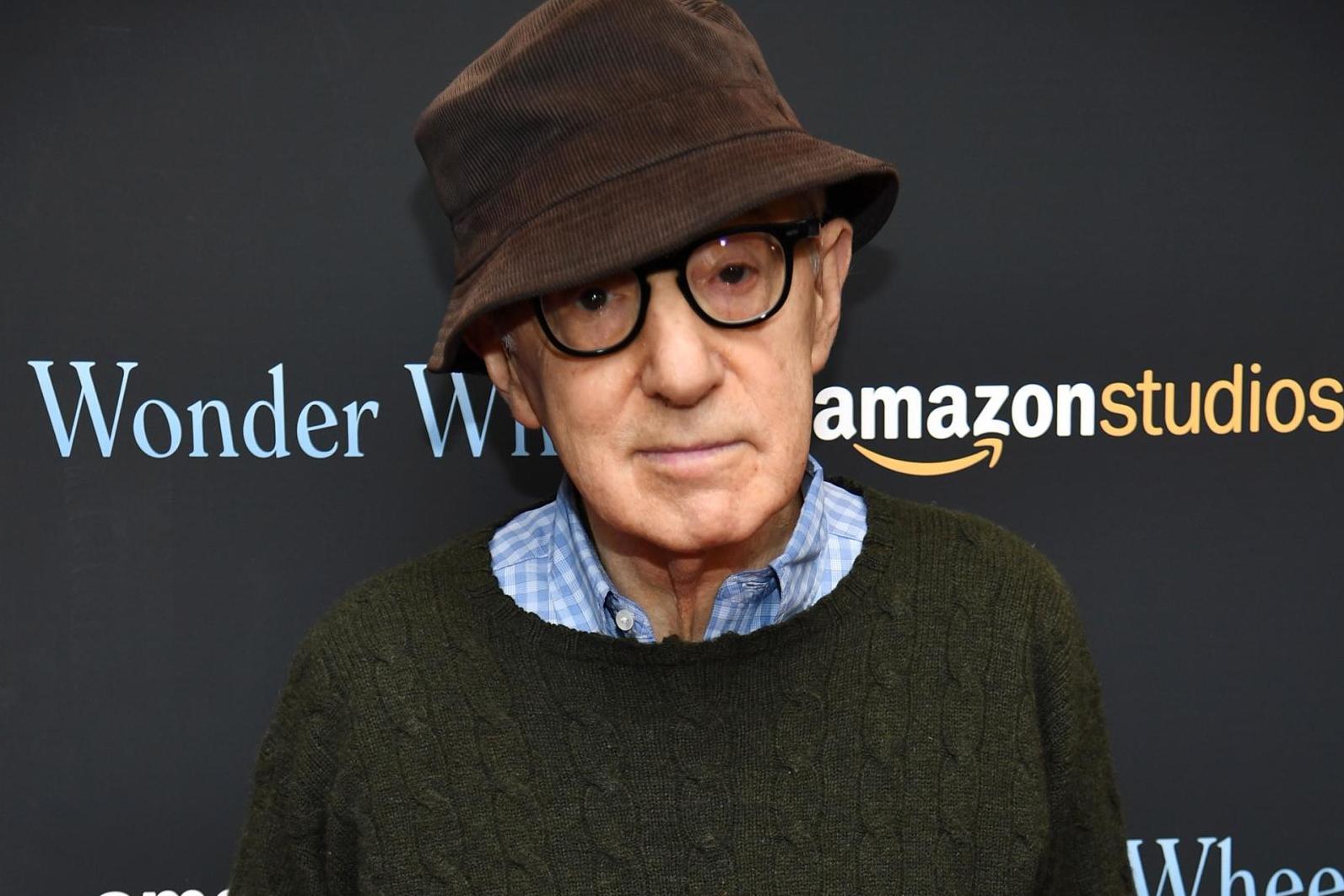

As a French person, I'm ashamed of how much my country protects people like Roman Polanski and Woody Allen

Woody Allen's A Rainy Day in New York is now being released in European cinemas, having been disavowed by its stars during the MeToo movement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For a while, it seemed as though A Rainy Day in New York, the film made by Woody Allen, would never accrue much global cachet. It was disavowed by its stars at the onset of the MeToo movement, when allegations of child sexual abuse made against Allen by his daughter Dylan Farrow resurfaced. Amazon shelved the film earlier this year amid the controversy and no distributor has picked it up in the US so far. Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Hall and Griffin Newman, who are all part of the cast, donated their salary to charities such as RAINN and Time’s Up, while Selena Gomez made a donation exceeding her earnings to the latter.

The message seemed clear: art matters, but so do sexual misconduct allegations, and stars no longer wished to be associated with Allen as long as those accusations endured.

That is, of course, until European distributors started picking up the film. As of now, A Rainy Day in New York is reportedly set for release in Italy, Austria, Germany, and – as announced on Wednesday – it will open the prestigious Deauville American Film Festival in France on 6 September, an honour previously bestowed upon movies such as Whiplash, Little Miss Sunshine and Maria Full of Grace. The movie is also scheduled for release in French cinemas in September.

As a French person who now lives in the US – and who has thus witnessed the impact of the MeToo movement on both sides of the Atlantic – I learned of the news with an energetic eye-roll and a touch of existential dread.

France’s record when it comes to men accused of terrible things is complicated at best, especially if said men have made substantial contributions to the cultural landscape. As we all know, Roman Polanski, the director of acclaimed films such as Rosemary’s Baby and The Pianist, pleaded guilty to unlawful sex with a minor in 1977 before fleeing the US and finding refuge in France, where he has lived ever since. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expelled him in May 2018. In April this year, Polanski took the situation to court and asked a judge to restore his membership; the Academy stood by its decision.

In France, however, Polanski is still treated like movie royalty. His films get screened at the Cannes Film Festival. High-profile actors play in them. His work regularly gets celebrated. The Polanski redemption tour has been going on for years now and it shows no sign of slowing down.

This all goes back, of course, to a question that hasn’t found a satisfying answer since MeToo went mainstream in October 2017: when artists are accused of terrible things, should we continue to consume their art? And should they be allowed to keep existing in our public consciousness?

I don’t know. It’s a complicated question, and I won’t pretend to have solved it. France has wrestled with it with renewed intensity in recent years, after singer Bertrand Cantat, who was convicted of murder in 2003 after beating his girlfriend, actor Marie Trintignant, to death, attempted a musical comeback. Many found the idea of Cantat enjoying fame again too distasteful to bear, but others argued that he has served his time and deserved to resume his activities like any other former convict. (Of course, in Cantat’s case, that meant appearing on the cover of one of France’s most prominent cultural magazines, which one might argue doesn’t fall quite within the range of regular professional duties, but what do I know?)

What I do know is this: trials by public opinion are a terrible idea, but what other options are we left with when someone pleads guilty then flees to a foreign country, never to be seen in a courtroom again? Certainly, people can keep enjoying whatever art they want, but are creators owed a platform, no matter the circumstances? I don’t think so, and in any case, I wish France would stop reinventing itself as a promised land for alleged abusers.

Ever since Catherine Deneuve and 99 other women co-signed an open letter taking a stance against MeToo, certain French clichés have been used and distorted as a sort of counterpoint to feminism. You don’t want to be cat-called? Come on, don’t be so frigid! Flirtation isn’t a crime! The French do it all the time! As if silencing people asking for more equality and respect were vital to preserving the free-thinking ethos we French are supposedly known for.

But here’s the thing: when France chooses to offer cultural asylum to people facing accusations like those made against Allen or Polanski, it sends a message. It’s a distraction, a way to put things on hold so that we never really get to the truth. With each Woody Allen film that gets released, with each Roman Polanski movie airing in Cannes, both men get to keep writing their stories while sweeping the most inconvenient chapter under the rug.

MeToo has been messy in many ways. But we are trying, collectively, to do a good thing. We are trying to lend a more compassionate, supportive ear to those who say they have experienced sexual violence. We are trying to raise our moral standards and build a fairer world. And when France rolls out the red carpet to men accused of terrible things, it creates more noise, to the extent that we despair of ever getting to the truth. It’s running interference on those men’s behalf. I think that’s a shame, and I wish my country would stop doing it.

Does this mean Allen should never release another film again? No. But it might mean that as far as Allen is concerned, we have more pressing issues to solve than whether his umpteenth film ever sees the light of day. It doesn’t mean never. It means not now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments