I encouraged my students to write warts-and-all confessional books. Then one wrote about me

My mom warned me that karma had come back to bite me — and I had to admit that she was right

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Did you read Mary Trump’s book?” I asked my mother.

“Another over-therapied writer airing her family’s dirty laundry in public,” my mother said. “I feel sorry for Mary’s aunt. The poor woman didn’t know she was being taped.”

Her comment stung; she was referencing me and seemed to be over-identifying with Mary’s unwilling subject.

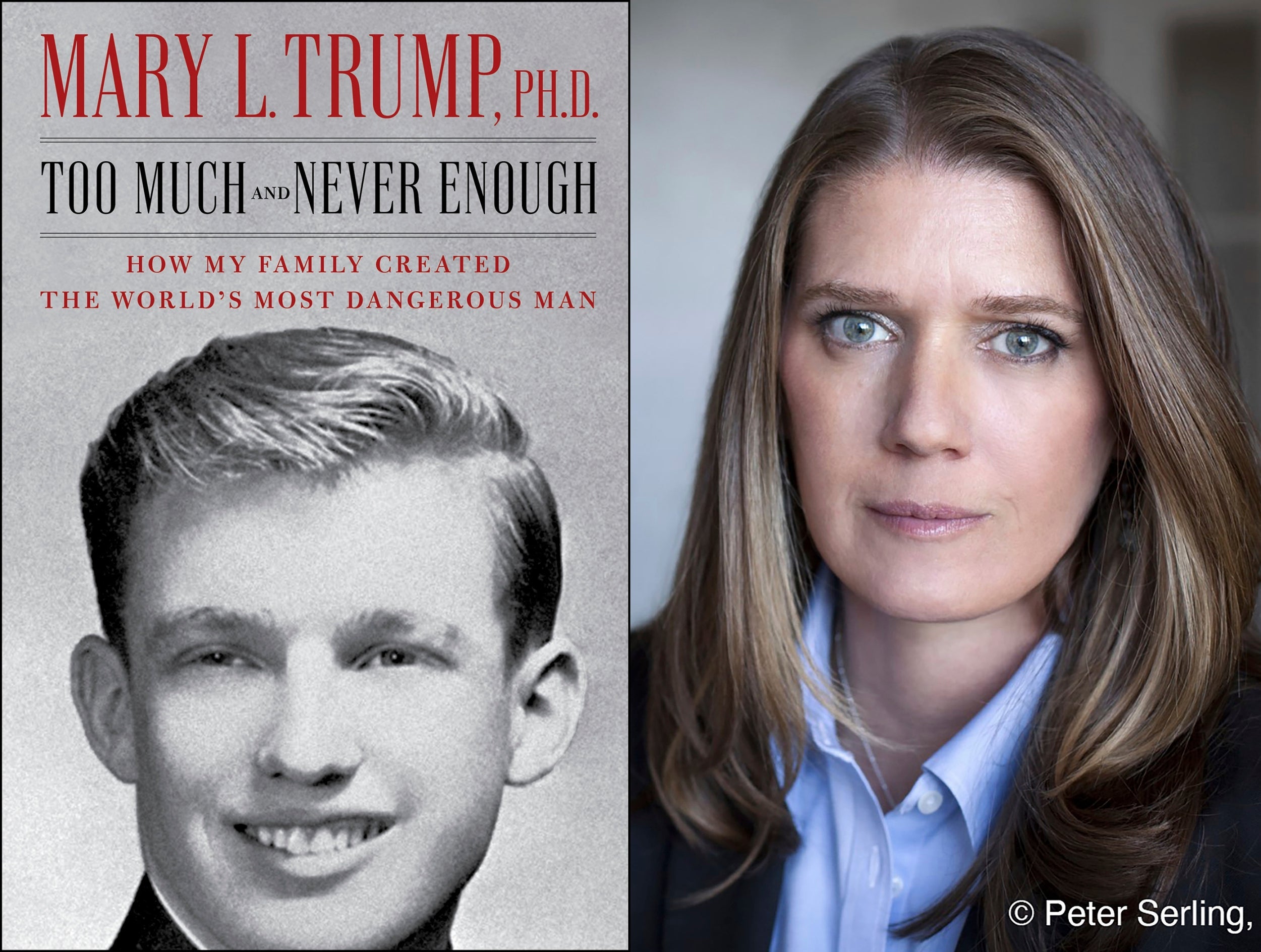

Fascinated by Too Much And Never Enough, I'd devoured the explosive bestseller about the Trump family that a judge affirmed Mary’s First Amendment right to publish. A left-wing New York memoirist and shrinkaholic her age, I admired her bravery for exposing the past of our dangerous president. Yet I also had a reason to fear being maligned in print.

"I need to hire a lawyer,” I’d told mom earlier that spring. “A student used my real name in her book without my permission, depicting me as a nutcase.”

"Karma come back to bite you," Mom replied.

I flashed back to selling my debut personal essay at 22 — about her — to a women's magazine.

"You made me sound like a bimbo," she'd yelled. "I should write a rebuttal about a daughter who lies about her mother."

My big conservative family wanted their personal lives private. No wonder I became riveted by the confessional poets. By 12, I was marching around our Midwest house, reciting Philip Larkin’s "They fuck you up, your mum and dad.” Analyzing emotional issues in verse earned ridicule from my intimidating science-brain dad and brothers. Scrawling feelings into my notebook was my shield, shelter, and sword. I was thrilled to be published in high school and college magazines.

But moving East for my MFA, I was devastated when my mentor declared my poems had “too many words, not enough music." He was a New York Times editor who, miraculously, preferred my prose. Reading my revealing essays in the paper of record felt like validation, as if achievement were redemption. It took until age 43 to sell my first book, divulging my worst breakup sagas. An old flame replied, "You've created a better character than I am a person." Another emailed "ha ha,” then never spoke to me again.

My husband allowed me to chronicle him - if I changed his name and omitted his age (fearing discrimination in his business). When someone asked about his portrayal, he joked, "You'll read about it in my book, The Bitch Beside Me.”

Teaching creative nonfiction, I suggested students mine their obsessions and share humiliating secrets, adding “The first piece you write that your family hates means you’ve found your voice." I repeated my Random House lawyer’s advice to change names, and use an author's note. (Mine read: "Names, dates and identifying characteristics of people in this book have been obscured so they won't divorce, disown, hate, kill, or sue me.") To win a lawsuit, the accuser had to prove you lied with malice intended and show damages. I noticed that Trump’s injunction to kill Mary’s book didn’t claim she lied. They argued the 55-year-old author had signed a confidentiality agreement barring the financial disclosures.

Unlike Mary, to avoid being sued and hurting feelings, I’d front-loaded my real-life characters with sincere flattery. My mother was a “domestic goddess, a cross between Ava Gardner and Lucille Ball,” before I called her out as an “over-feeder.” Dad, from the Lower East Side, was brilliant and "handsome as a gangster" before he was "a chain-smoking oncologist." I’d also attempted to emulate my idol Philip Roth — who'd immortalized his New Jersey clan of Jews — and re-imagined my story as fiction. I assumed it gave me more leeway, since everyone knew novels were made up. My friend-turned-sister-in-law sanctioned a humor piece about how, after I invited her home to Michigan, she married my doctor brother and had four kids — like my mom, becoming the suburban daughter my parents always wanted. I later offered her a first look at the novel I’d expanded it into. “If you publish it, then I’ll read it,” she'd sniffed.

She did, in hardcover. Though she'd refused my offer to preview the pages, she was still offended. Anne Lamott said, “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better." But my shrink reminded me, "You can be very right and very alone." I apologized, since my brother was more important to me than winning the argument.

After that, I showed my sibling work about him first to get his approval. I also deleted details that bothered my mate (so we'd keep mating), middle brother (an IT guy I adored – and, as a technophobe, couldn't afford to lose) and therapist, hero of my addiction memoir.

Since I'd only been written about fondly, I assumed I'd always enjoy reading reflections of myself. The first time I didn’t was in 2014, when I was misquoted by a 22-year-old student who audited my class. She'd asked my opinion of several essays. “This is the most interesting,” I’d said, of her exploration of dating with disabilities. I suggested an editor, who bought it. My student’s subsequent piece complained her teacher called her disability “the most interesting thing about her.”

“That's not what I said,” I emailed, outraged. “You'd showed me bloodless subjects. I praised the one about your love life because it was most revealing. Indeed, in class I often repeated Arthur Miller's advice to tackle ‘the unwritten, the unspoken and the unspeakable’ and Philip Lopate's line 'the problem with confessional writing is that people don't confess enough;. My theory for being vulnerable was: ‘Make me think you might not be okay’.”

She’d implied I was insensitive to disabled students, but I’d actually made exceptions to let her attend for free and hand in work late. She later admitted I spoke so quickly she often couldn't hear everything clearly — after the damage was done. Joan Didion said, “Writers are always selling someone out” and “Writing is a hostile, aggressive act.” Motivation was key. There was a difference between warning the country of peril versus chasing after bylines, “likes” and checks.

Although I’d scorned the Trumps’ penchant for nondisclosure agreements, I insisted my classes and pupil-teacher talks were off the record: no videoing, posting, tweeting, Snapchatting, TikToking or (mis)quoting in the press.

That mandate was broken when I read the 2020 galley by the memoirist who used my real first and last name, my school, and (incorrect) class title. She depicted a cool professor who helped launch her career, but the inaccuracies were jarring. She described me texting her late at night, out of the blue, to do a walking office hour around the local park, leaving out that she'd just read aloud a piece about dropping out of her previous college after being raped. Arriving home at 10pm to find a flurry of her emails, I asked my professor husband's advice in case a student was triggered reliving a sexual assault. He suggested I check on her. She lived nearby, so I asked her to take a walk to see how she was. Although she seemed fine — giddy, even, firing off career questions — I gave her the number of a therapist she later saw.

After class ended, she remained my walking partner, asking advice about marriage and manuscripts, recording my answers on her iPhone, teaching me to track the four or five miles we’d trekked on mine.

A separate chapter had me urging her to leave her husband who had “crucial fingers missing” when I’d just quoted a breakup poem by Sandra M Gilbert: “You knew he’d enlisted under a blank banner, knew/he was missing crucial fingers..." (Didn’t she check her iPhone tape?)

These discrepancies were disturbing, implying I stalked students at 3 a.m. and pushed her to divorce. (Not so. Her ex was a former student I admired.) I taught college part-time, but had applied for full-time professorships. The representation of me as someone who’d text students to hang out at all hours could damage my job prospects and university standing. Since I wasn’t a public figure, I asked her to disguise my identity.

"My memoir comes out in six months. My editor said it's too late to make changes," she'd replied, refusing.

That wasn’t true; I’d made revisions two months pre-publication in my own books. After my lawyer sent a strongly worded letter, her editor agreed to give me an alias.

"I can't believe her publisher didn't make her change names, like mine did," I’d texted Mom.

"She was emulating you!" she’d replied, her laugh emoji gloating.

All these years later, I finally saw my mother's perspective. Authors had all the power to project their vision of the world, however skewed, vengeful, myopic, or mistaken. I applauded Mary Trump’s end goal. What rational person wouldn't? Still, I also sympathized with Trump’s sister Maryanne, the discrete 83-year-old judge (labelled “a radical pro-abortion liberal” by Ted Cruz), whose private conversations were secretly taped and aired. She was guilty only of her lineage, caught in the crossfire. Would it ruin her relationship with her sister and only surviving brother, or her reputation? Nowhere was our speech sacred or protected from being exploited by a writer — not on a walk, a classroom, or in your own living room. Even a well-intentioned portrayal could backfire and hurt somebody irrevocably.

I suddenly saw the harm my words had caused. My humorous piece on needing a shrink to write a book with my shrink neglected to clarify that our therapy had ended when he moved away. Negative reader comments about the dangers of a “dual relationship" bothered him. In my addiction memoir, I showed an editor smoking and drinking too much while I was getting smoke-free and sober. I changed his name and gave him a heads-up, but it ended our friendship.

Reading my student’s finished book, I was pleased her mentor was now called "Professor Nicole Solomon,” but disappointed to no longer be in her acknowledgments. I emailed to ask if my insistence that she obscure my identity caused her to erase me.

"No. I'd never take you out," she said. "Look." She screen-grabbed the lines: "I have limitless gratitude for Nicole Solomon, the most generous professor and friend a young writer could meet."

I was moved, albeit wary to read future recreations of me by all the fellow confessional writers I’d unleashed. Unless I had a perilous politician to expose, I vowed to disguise names and details better, and to show more subjects my words pre-publication, remembering how it feels to be on the other side of the page.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments