The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

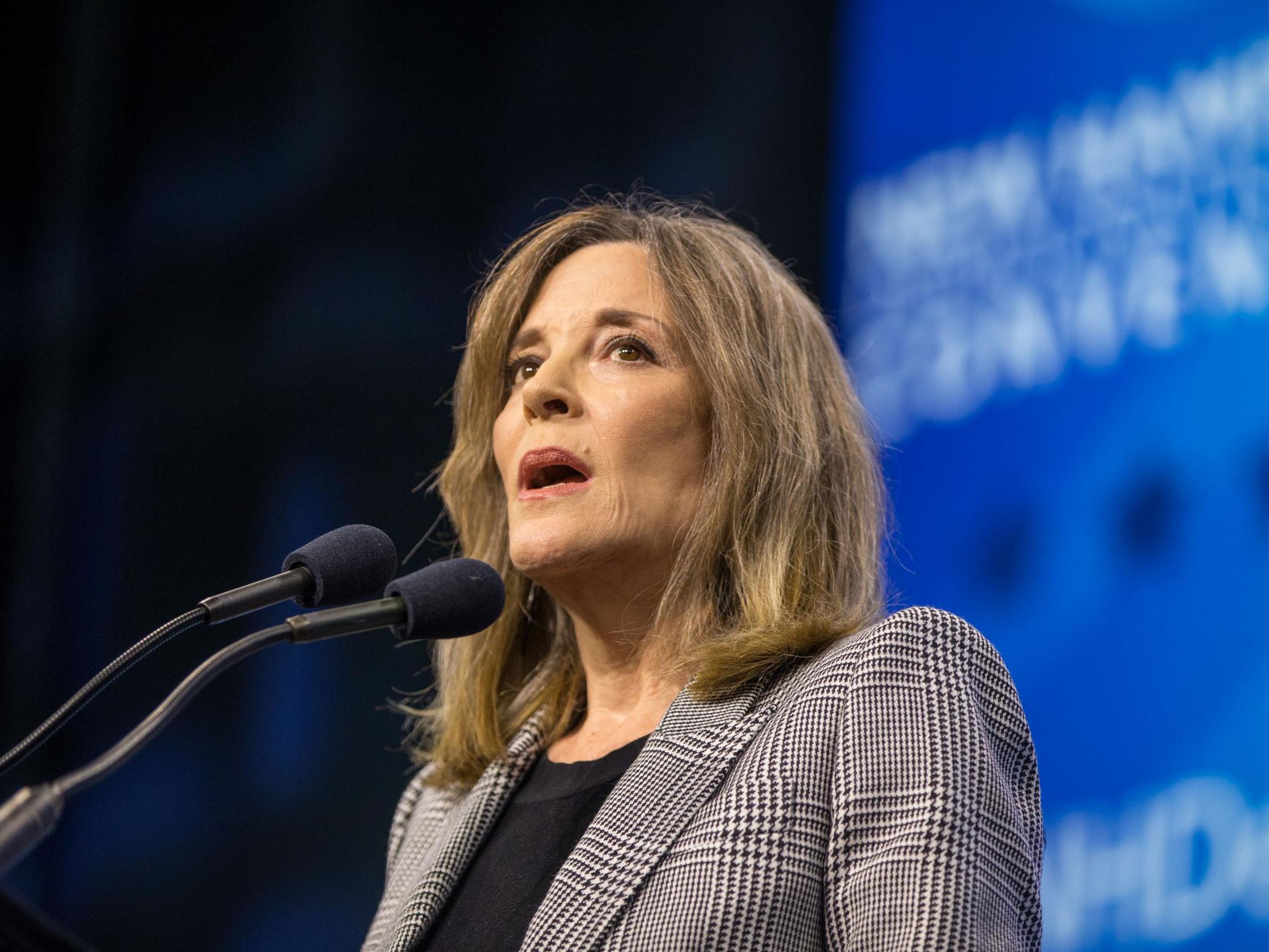

No, I don't want to hear you say Marianne Williamson has 'gone back to her planet'

She was a joke, a Republican favorite, a writer sometimes mistaken for Nelson Mandela. But underneath the memes, Marianne had something to tell us about the state of America

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.She was a joke candidate, everyone decided. She was funded at least partly by Republicans determined to get Trump back into the White House in 2020. She was possibly a Russian asset. She believed in chemtrails, crystals, and “dark psychic forces”, and described herself on Twitter as a “non-denominational faith leader”. She officiated one of Elizabeth Taylor’s weddings. She once said Americans could will hurricanes away from cities with their minds.

Hardly any of that is true (the Liz Taylor one is, FYI), but it doesn’t matter. People were good at finding the ridiculous in Marianne Williamson — at pointing to her self-help books and her “spiritual adviser” work with Oprah, for example, rather than the successful nonprofit she founded in the 1980s to deliver food to housebound AIDS patients. And she could, of course, be her own worst enemy. Nobody has forgotten her promise at the first debate that she would call up the prime minister of New Zealand from the Oval Office to say, “Girlfriend, you are so on.” Her clichéd hippie phrasing obscured the fact that she had actually been talking about something very important: the fact that American children have shockingly bad educational and health outcomes for such a wealthy country. She did actually, as Elizabeth Warren would say, have a plan for that. Her website detailed her desire to open a cabinet-level Department of Children and Youth that would provide wraparound care in order to reduce America’s high infant mortality rates, and provide psychological support for children with PTSD. She wanted a holistic educational system akin to Canada’s and a new national standard for youth in care. Her ideas for schooling and higher education were borrowed from success stories in western European nations like the UK, Germany and Finland. She even had economically thought-out ideas for how a student loan amnesty might be achieved.

There were kookier proposals, too. She wanted a referendum on national service which only Americans between the ages of 18 and 30 would vote in, for example. But most of her ideas were the sort of thing everyday liberals would readily support: sensible animal welfare standards; disability justice; urgent commitments to the environment; moving the punitive American criminal justice system more toward rehabilitation. In other words, her campaign promises didn’t read like she’d just woken up in the middle of the night inspired by the divine spirit of self-empowerment and decided to run for president. They read like she’d considered what leadership of a country like the US should look like. They read like when she said she wanted to be in the White House, she really meant it.

Her announcement that she was ducking out the race was classic Marianne. “These are not times to despair; they are simply times to rise up,” she urged her followers. She spoke about how she had wanted to make “humanity itself America’s greatest ally” and to bring in “more mindful politics” by “initiating a season of moral repair”. It was florid language, but some of it was surprisingly impactful. We should work on “repudiating the corporate aristocracy”, she said; it was an astonishingly apt way of describing the situation in America today, where a country which crows about escaping the clutches of a monarchy still suffers from some of the worst economic inequality in the world. The message ended with a promise to support whichever Democratic hopeful won the candidacy and a picture of her “Marianne 2020” bus at sunset, a rainbow breaking through the clouds.

It’s easy to ridicule optimism, and Williamson had optimism in bucketloads. In a surprisingly tender profile in The New York Times in September, Taffy Brodesser-Akner described the unexpectedly electric feel at rallies and meetings she'd been told would be unremarkable. Brodesser-Akner described how she'd gotten the gig in the first place: "Literally every other major candidate got jumped on by our very competitive political staff, and as they went to war over Pete Buttigieg and were picking the bones of Joe Biden from their teeth, I asked if I could write about [Marianne], and they shrugged and said, Yeah, sure, fine, we guess". Williamson was clearly cautious about the fact that she was being trailed by a writer who usually covered celebrities and movie stars rather than serious political contenders. “Unspoken between us,” Brodesser-Akner wrote, was a question Marianne seemed dying to ask: “What does it mean that they sent you?”

What, indeed? In a country where unqualified candidates put themselves forward for the presidency all the time, it seems absurd that Williamson was seen as so unacceptably ineligible. “She’s returning to her planet,” tweeters wrote as the news of the end of her campaign broke, “Goodbye to the Gwyneth Paltrow of Jill Steins.” Gifs of unicorns and aliens abounded; the lyrics of So Long, Marianne were shared with particular emphasis on the part about needing to laugh about it all. The mockery was instant and obvious. Yet Williamson outlasted her two fellow Texans in the race, Beto O’Rourke and Julian Castro (Castro just by a whisker, admittedly.) She stayed longer than Kamala Harris and she raised more than Kirsten Gillibrand. She meant something beyond memes, even if not everybody liked that.

Andrew Yang is a businessman offering free money to every American citizen. Pete Buttigieg is a mayor of a small city in one of the smallest states in the country. Ronald Reagan was a movie star. We live in a world where male celebrity is presumed to be the result of clever handling and female celebrity is presumed to be down to luck. A prolific author — and what is a successful author, really, but a self-made businessperson? — with a good track record in nonprofit work is not so far removed from others who have put themselves forward for public office. She is certainly not less qualified than a wealthy heir who fired people on TV for entertainment.

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure,” Williamson wrote in A Return to Love. It is a quote so widely misattributed to Nelson Mandela that Williamson herself addressed the fact (“As honored as I would be had President Mandela quoted my words, indeed he did not.”) Williamson is an expert at such pithy aphorisms, which she peppers throughout her books, speeches and occasional poems. They are the sorts of lines that one can imagine being shared on Instagram posts, pasted over an image, perhaps, of a wild horse running across a beach: shared by an audience of predominantly young women, easily derided.

Marianne Williamson was never going to be president. But in losing her, we didn’t just lose a joke. We lost a valuable lifeline to a group of potential voters who rarely turn up to the ballot box (the New York Times profile noted that many Williamson supporters who turned up to her meetings were people who had only developed an interest in politics through familiarity with her.) She also pointed to a mindset that a lot of Americans share. Willing a hurricane away with your mind sounds ridiculous but, as Williamson herself said, the difference between that and prayer is merely “semantic”. She spoke in the language of god-fearing religious Texans — she once proclaimed that everywhere is “a front for a church” — and she introduced people to liberal ideas through that. It was, well, clever.

Additionally, a distrust with “Big Pharma” is something she didn’t start, but she did shine a light on. Williamson’s position on vaccinations has always been muddled — a New York Magazine article titled “Where does Marianne Williamson actually stand on vaccines?” pretty succinctly summarized the confusion — and although she at one point during her campaign said she was “pro-vaccination”, she had also in the past referred to controversial “vaccine skeptics” as “experts” on her radio show and talked about vaccines causing autism. Ironically enough, the suspicion toward physicians and pharmaceuticals which feeds unfounded paranoia about vaccines probably arises from the same healthcare problems Williamson diagnosed and promised to overcome. Profits and disease outcomes do go hand-in-hand in America; doctors do have unacceptably cosy relationships with drugs companies; the opioid crisis happened because something in this relationship went terribly, terribly wrong. Someone has to reckon with this legacy at some point. She is hardly the only person to have opened up a discussion with anti-vaxxers.

As Williamson drops out the race, we should be wise enough to take something valuable from her campaign rather than dismissing it as a mad, bad combination of malicious entryism and meaningless self-help sorcery. America is in a cynical place right now, a place where people think “all politicians are corrupt anyway”, a place where people distrust the authority of their doctors, their leaders and their experts alike. Some of those people were Marianne’s people, tempted out of the woodwork by a promise of something new. Democrats shouldn’t forget them now — or they could well be Trump’s people come November.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments