This is how it feels to live with someone who is terminally ill

In her first interview since the death of Dame Deborah James, the bowel cancer campaigner’s mother said the hardest part of her daughter’s illness was knowing she was going to die – I had no idea just how hard that would be

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

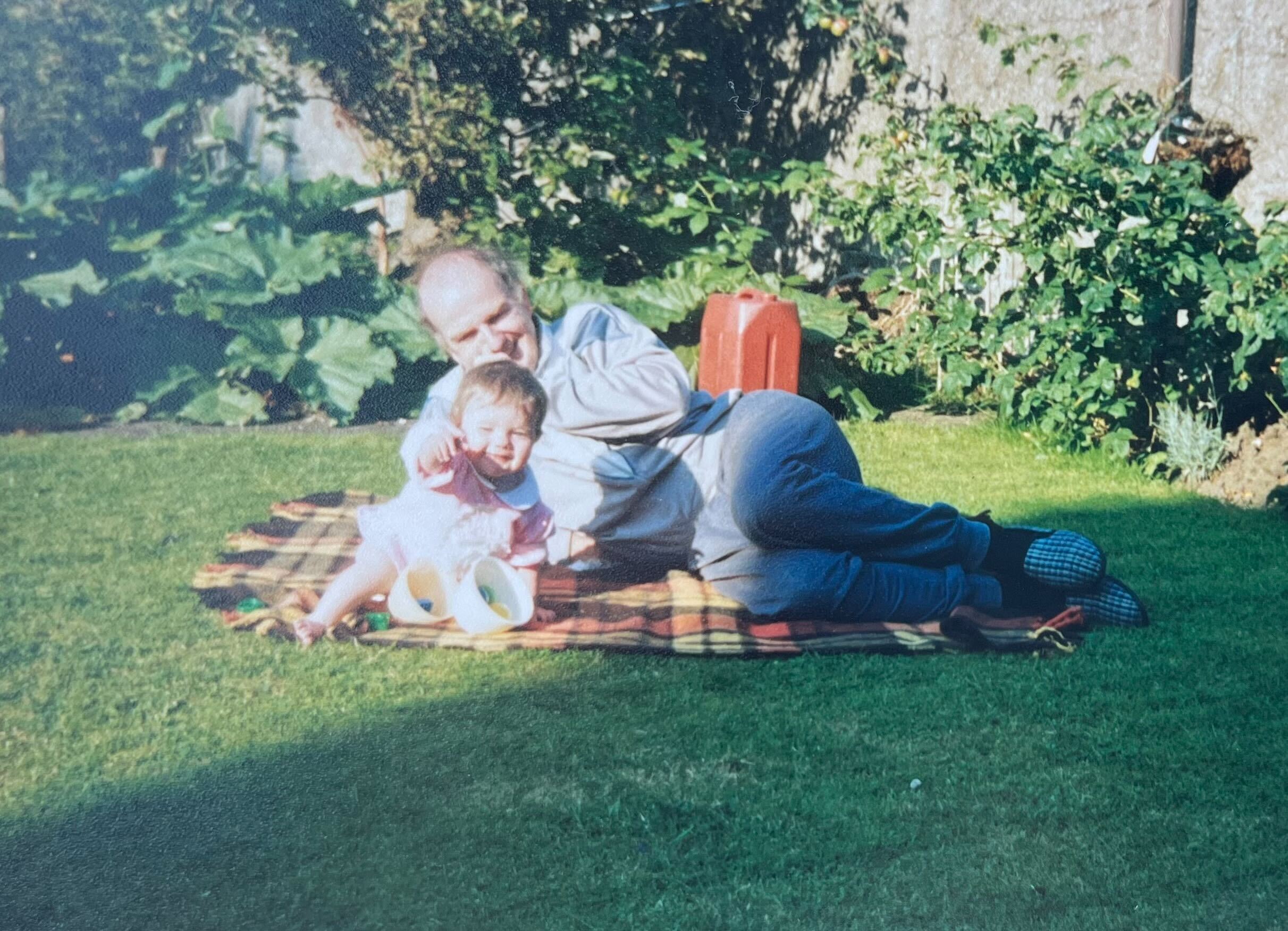

Your support makes all the difference.It is a strange thing to grieve while the sun is shining. While the Earth is going through record-breaking temperatures that have set forests and homes ablaze, my own world is weathering a different kind of emotional inferno: the impending loss of my beloved father.

In her first interview since the death of Dame Deborah James, the bowel cancer campaigner’s mother said the hardest part of her daughter’s illness was knowing she was going to die and being powerless to save her.

This is the excruciating reality for the family of anyone living with a terminal disease; the unshakeable knowledge that no matter how much you love them, how capably you care for them, there is nothing you can do to keep them with you. It is inevitable.

In the seven months since my dad was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer after months of a persistent cough and a lifetime without cigarettes, life has been turned on its head. All illnesses are heartbreaking, but it is a particularly cruel one that dismantles the host it lives within, piece by piece until they are scarcely recognisable from the person you once knew.

Cancer crept insidiously inside our house and brought with it an unwanted collection of strange accessories. A palliative exercise bike. Clunky orthopaedic cushions. Pamphlets dictating how best to care for someone with a mounting mound of needs. Pills, pills, and more pills.

Plans for family trips have morphed into a cyclical chemotherapy schedule. Rambling coastal walks have become stunted shuffles down hospital corridors. “Good nights” are no longer evenings at the theatre, merely ones without too much discomfort or pain. Where once there were dinner conversations peppered with laughter, now only tearful pleading: “Please dad, you’ve got to eat.”

There is no “right” thing to say to someone staring down the barrel of irreversible loss, but there are WhatsApp messages seeing “how you’re doing today – no pressure to reply”. There are Deliveroo lunches because you’ve probably forgotten you need to cook for yourself. There are unprompted voice notes detailing disastrous dates that spark half-smiles and bring momentary distraction. There are cakes and flowers left at the door. There are calls to say: “I’ve kept Saturday free, even if you’re not.”

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The most touching act of kindness ironically left me bereft in my parents’ driveway, thick tears coursing down cheeks as I clutched a house key in one hand and a pair of navy Marks and Spencer pyjamas in the other. The man in the hospital bed next to my father’s had befuddled doctors with some form of mysterious malady for some time, but it was clear to all – medically qualified or otherwise – that he suffered acutely from at least one condition: kleptomania.

This patient had deftly plucked my dad’s pyjamas from a bedside locker and taken to reclining in them, resplendent, in his plastic-covered crimson armchair. Brazen and bold, the robbery brought light relief to an otherwise hopeless situation; the ward burglar became a rare source of laughter. I recounted the story to my best friend on a Friday night, and by midday Saturday the replacement pyjamas had been deposited on our front doorstep.

It is acts of kindness such as those that help you to carry on living when someone you love is dying.