The worst thing about breaking up with someone isn’t missing their presence, but their words

Ask a couple what they call the remote control and you’ll find yourself at the heart of a very private, very intimate love

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I recently responded to a callout by a writer and fellow journalist on Twitter for the signals (and symbols) of a committed relationship; “the joys and the mundanities” of domestic harmony.

Thousands responded with their own unique hallmarks of long-term love: from shared meals and virtual shopping lists to unique holiday traditions; from knowing how someone likes their tea to leaving the tomatoes out of a dish because your partner can’t stand the texture. One person wrote movingly about being widowed at 34 after 10 years with her husband. “The mundane is what you miss the most,” she said. “How they stack the dishwasher, or the crumbs after breakfast.”

I had my own thoughts as I browsed the list, each memory a pleasurable (yet painful) joy: sitting in a room watching TV or playing a video game, your feet casually slung across their lap; the way someone might take extra care to spread butter on a piece of toast for you, going right to the corners. Small, everyday, barely noticeable intimacies, such as grabbing their favourite hoodie – the one with the ragged sleeves – when they mention that they’re cold. Picking up a bag of liquorice in the supermarket just because you know they like it.

There are hundreds of ways to say – and show – “I love you”, but the entire thread made me think of one outstanding (and, frankly, fairly weird) element of any close partnership: language.

The special, silly words a couple share when they form a romantic bond is something I don’t think can be replicated – they are unique to that pair. People who fall in love inevitably and effortlessly put together a secret dictionary made up of nonsensical names for cats (as I replied on the thread, a relatively “standard” name for a pet might begin as “Ginger” but end with you both calling him or her “Lord Foxington of the Third Realm”, whereby “Ginger” becomes “Foxy” and nobody can quite remember, or explain, why).

Then, there are the pet names for each other that neither would feel entirely comfortable shouting out in a busy supermarket; inexplicable ways to refer to a favourite chair; a well-worn phrase when it’s time to go to bed (“Are you taking the train to Bedfordshire?”); snatches of songs with the words changed around – and you’ll never sing it any differently. Not now, not ever.

Ask a couple what they call the remote control and, I believe, you’ll find yourself at the heart of a very private, very intimate love – by way of “oofer doofer”, or “thingy”, or even “big boy”.

This goes for platonic relationships sometimes, too, of course – my closest university friend and I refer to each other by the same pet name (and variations of it, sometimes solely an initial); my children and I have a code that we shout out at irregular intervals in our house when any one of us feels like it, and the onus is on everyone else to respond in kind. It’s a made-up word that wouldn’t make a jot of sense to anyone else listening in – to anyone who doesn’t live with us – but what it means is “I love you”.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

I’ve noticed, too, that when I become close to someone, or forge a special bond – especially if there are inklings of romance – our conversations become loaded with new language. We invent acronyms, revel in references to moments only we have talked about or shared. If we were ever asked about them in a pub it would be overwhelmingly tempting to cold-shoulder the asker: “It’s an in-joke; you wouldn’t understand.” The individual make-up of the letters is far less important than what it signifies – for what it means is intimacy.

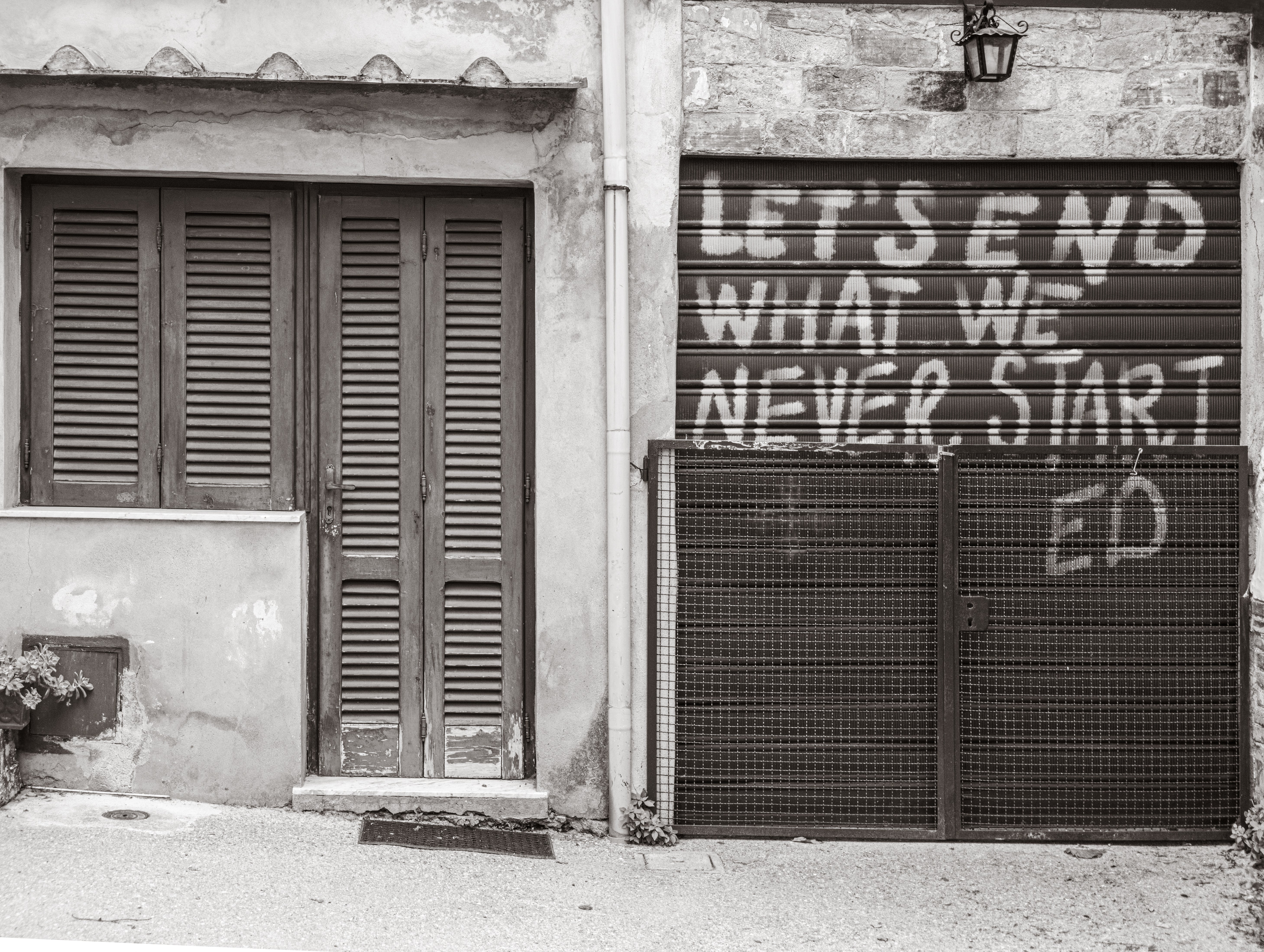

That’s because, I believe, private language exists in a soft-edged, dyadic vacuum, formed when you pledge your heart to another. It lasts for as long as the relationship is in bloom. And, much like a beloved houseplant or a rose, it withers and dies if it’s not fed.

I’m fascinated by what happens to all that “love out loud” when a relationship ends or fades away. Does this special lexicon die too? Or does it simply disappear for a while... lie dormant? What happens if you’ve only ever used a pet name for someone, then lose the right to call them that when you split up? How do you possibly “rename” someone – when their actual name feels like a small and unfamiliar violence at the back of your throat?

If you’re not steadily and regularly using a language, it can feel alien against your tongue; any student who is 20 years out of studying GCSE French knows that. But what we don’t talk about very often is how painful the loss of that language can be, beyond a break-up – how it becomes a unique and tangible grief for which none of us (aptly) have the words.