Lie or lose? Deception has become a political survival technique

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most of us use the internet acronym LOL to mean “laugh out loud”. But in US political circles, where campaign strategists are supposed to have superpowers, it stands for “lie or lose” – the public doesn’t like the truth, and those who flirt with telling it don’t stand a chance.

There is no such thing as an outright political lie. Instead there’s distortion, exaggeration, misrepresentation, deception, half-truth and overstatement. The assumption is that the risk is worth it. Hubris and narcissism mean the consequences of a politician getting caught are outweighed – they think – by the benefits of telling voters what they want to hear. They know we seek support for our preconceived notions, and avoid information that challenges established views.

Strategists assume voters have an almost infant-like response to lies, believing that if something isn’t true it won’t be repeated. So the most effective political lies are repeated again and again. Say something often enough and people will begin believing it.

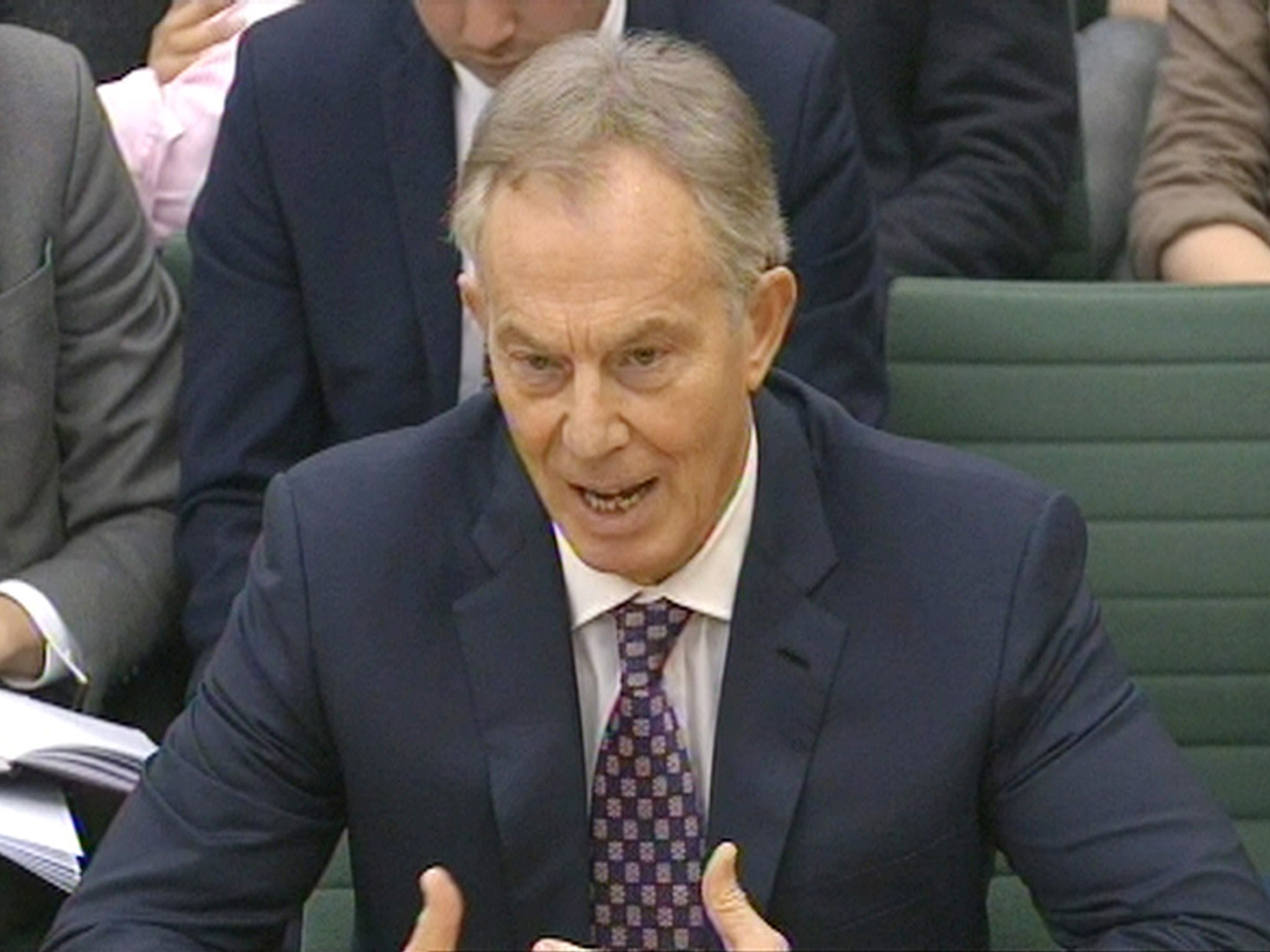

As the frontline battle in most democratic politics centres on winning, lie or lose is a common theme. Ask Sir John Chilcot. He’s spent six years and £10m on a complex LOL puzzle involving Tony Blair and the Iraq war.

Deciphering, or even defining, a political lie doesn’t usually fall to a court. But now and again the law makes an effort to help out. Just before May’s election, Alistair Carmichael, then Scottish Secretary, authorised his special adviser, Euan Roddin, to leak a memo claiming that the SNP leader, Nicola Sturgeon, secretly preferred David Cameron remaining in Downing Street to Labour winning power. Reports of a conversation between the Scottish First Minister and the French ambassador, Sylvie Bermann, were quickly dismissed as untrue by both sides but nevertheless undermined Ms Sturgeon’s claim that she wanted a “progressive alliance” with other left-leaning parties.

Mr Carmichael first denied he’d leaked, but when the net closed in on him and his adviser he fessed up. Although he won the Liberal Democrats their only seat in Scotland, there was a legitimate question to be asked: did the lie mean he had misled voters enough to merit defenestration? Last week two judges in Edinburgh ruled that Mr Carmichael had indeed told a “blatant lie” – but the pair were also satisfied that the MP made the false statement of fact “for the purpose of affecting (positively) his own return at the election”.

In 1988, during the US presidential race, George Bush Senior said: “Read my lips, no new taxes.” Most economists in the Treasury knew that was probably a classic lie or lose exercise, and Mr Bush believed the White House would be his if he simply told America what it wanted to hear. Likewise, Mr Carmichael acknowledged that he thought it would be “politically beneficial” to leak the memo. In other words, at this particular LOL crossroads he opted for a survival technique yet to be explored by Bear Grylls: he lied. Should we be disappointed? Yes. Should we be angry? Of course. Should we be surprised? No. The former Cabinet Secretary, Robert Armstrong, once defined a lie as a “straight untruth”. Alan Clark, in the Matrix Churchill case in 1988, famously rephrased a Whitehall term with “economical with the actualité”.

The primary role of the Fourth Estate, the media, is to act as a lie detector, and that – more than courts – acts as a deterrent to politicians. Do papers behave? Not always. Russia had a century of Pravda – that means “truth” in English.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments