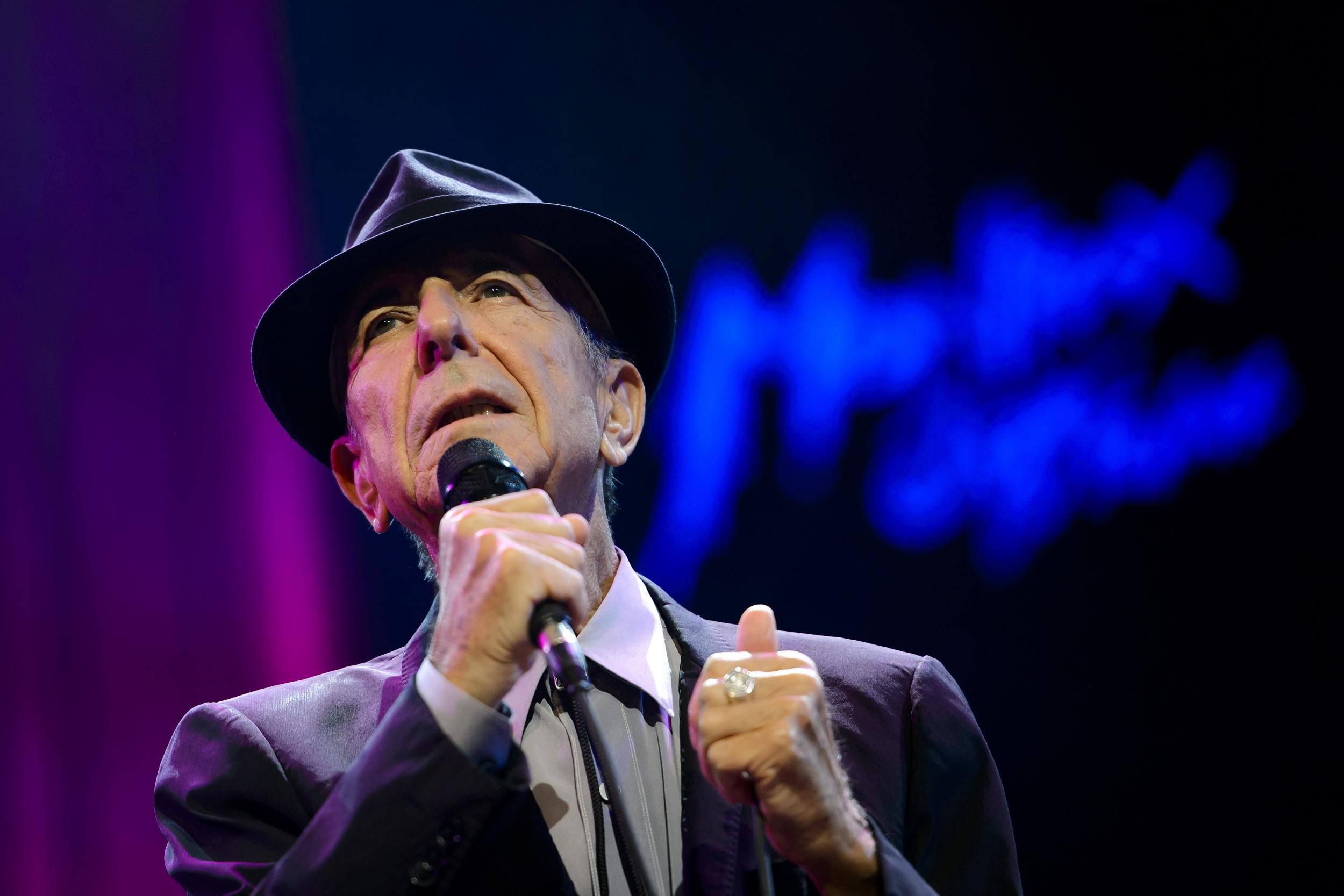

Nothing Leonard Cohen did should have worked – and the fact that it did is testament to his unique brand of genius

When Bowie was creating the character of Ziggy Stardust in the early Seventies, Cohen was signing off songs with his own name – ‘Sincerely, L Cohen’ on ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’ – erasing the line between his person and his persona just as Bowie was applying another layer of make-up to his

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The opening line of “You Want It Darker”, the first track of the album of the same name, his fourteenth, his last, which Leonard Cohen released last month, was a gut punch of a thing. Even by the standard set by the starting points of his other records – Songs of Love and Hate’s “Avalanche” of finger picking, say, or the synth stomp of “First We Take Manhattan”, it hit hard. The voices of the Shaar Hashomayim Synagogue Choir sound, the arrangement immediately makes it sleazy, in that magical way of his, and then a voice of almost unrecognisable, almost unbelievable depth intones the words, “If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game”, and the listener has to sit down for a second.

The first time I heard it, the directness was a relief: the choir, a swampy hook, a Hammond organ; poker metaphors and extracts of scripture circling the repeated line, “You want it darker”, expressed without a question mark, as a statement of fact. Oh Leonard, of course we want it darker when you’re the person preaching, just as our usual spider sense of a gothic cliché too far or the line between good and bad taste, when it comes to backing tracks, evaporates the moment you started singing. How else to explain why the first track I think of when asked for my favourite Leonard Cohen song is the magnificently silly “Jazz Police” from I’m Your Man, an album that came out precisely 38 days before I was born?

Now You Want It Darker provides both the best words to make sense of this miserable year – does anybody want to play this game any more? – and the first of 100 hints that this was an album about being ready for death, as he put it in a recent New Yorker profile, after all. It’s not another Blackstar, though – a record that real life, or rather death, suddenly decoded with an omniscient flourish, making one wonder whether Bowie had really died or actually left this world for another.

Of course it’s not: when Bowie was creating the character of Ziggy Stardust in the early Seventies, Cohen was signing off songs with his own name – “Sincerely, L Cohen” on “Famous Blue Raincoat” – erasing the line between his person and his persona just as Bowie was applying another layer of make-up to his. You Want It Darker doesn’t pretend it’s anything other than an album about mortality, in other words. It’s just that we weren’t to know, until now, that it was the album about mortality, in a career that hasn’t exactly shied away from the subject.

Cohen did reinvent his sound, though, most dramatically on Death of a Ladies’ Man, a Phil Spector-produced curiosity memorably described by Paul Nelson as “the world’s most flamboyant extrovert producing and arranging the world’s most fatalist introvert”. What the reviewer wasn’t to know was that the introvert in question had a taste for bombast that initially appalled fans of his first three albums.

It was certainly rather shocking to me, when I came to Cohen for the first time, via the same route – I suspect – as a lot of my peers: by going to the source of cover versions of, primarily, Jeff Buckley’s take on “Hallelujah”, but also stripped-down versions of I’m Your Man tracks by Nick Cave and the Pixies. What on earth was this? How was it possible that the songwriter responsible for these lyrics could also think that a little trill of electric piano after the words “secret chord”, and a massive gospel choir, were good ideas?

An easier, but less ultimately enriching route in – because once you “get” the central paradox of Cohen’s songwriting, everybody else sounds thin and limp in comparison – would have been a track like “The Partisan”, a French Resistance song adapted and translated into English by Cohen. Perhaps the best illustration of all of his genius for story-telling, it’s particularly difficult to listen to today: “There were three of us this morning, I am the only one this evening, but I must go on.”

And go on he did, not just with the impossible energy that meant he was able to tour for a large portion of his seventh decade on earth (to recover the money stolen from him by his manager) but also with enough good ideas to fill three albums in the past six years, at least two of which are among his best.

Now it’s up to us to do the same. 2016 has been the worst. I really hope I never experience another year like this in my lifetime. I feel completely desensitised by bad news now, to the point that it’s very difficult to find the words to express sadness about the death, and gratitude for the life, of Leonard Cohen.

But if there’s one thing that makes going on feel like a more appealing notion, it’s the fact that these brilliant souls who never ran out of words – Bowie, Prince, you know the list – stuck around long enough to produce some of their finest work while people like me were alive to see them do it. It shows us that there might be truth and wonder in these years, too, and not just a shimmering past, like Cohen’s, full of glamorous shadows – Janis Joplin here, Allen Ginsberg there – and a magnificent, magnificent “Tower of Song”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments