Accountability does not end with Hillsborough, the South Yorkshire Police need to be held responsible for Orgreave

If the police pre-planned a mass, unlawful assault on the miners at Orgreave, and then sought to cover up what they did and arrest people on trumped-up charges, we need to know

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The unofficial motto of policing in this country says that “the police are the public and the public are the police.” Those words, first spoken by the founder of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Robert Peel, sum up “policing by consent”, the operating model that makes British policing unique. They lie behind all of the Government’s police reforms, such as the record reduction in stop and search, work to reduce deaths in custody, the election of police and crime commissioners, the publication of crime maps, the more powerful Inspectorate of Constabulary, the removal of central government interference from local policing, the introduction of Police Now and direct entry into the senior ranks, the creation of the College of Policing and the changes imposed on the Police Federation.

Peel’s words also lie behind Theresa May’s determination to uncover past miscarriages of justice and abuses of power. Whether it is the failure of important institutions to prevent child abuse, the harassment of Stephen Lawrence’s family, the botched and possibly corrupt investigation into the murder of Daniel Morgan, the misuse of undercover policing practices, or Hillsborough, since 2010 the Government has shown it understands that justice must be done no matter how long it takes, and that to get things right in future, we have to understand what has gone wrong in the past.

As soon as the Hillsborough inquests delivered their historic verdicts, the calls for an inquiry into the so-called “Battle of Orgreave” on 18 June 1984 grew louder. Unlike at Hillsborough, when 96 people were unlawfully killed, nobody died at Orgreave. But the allegations about the conduct of the police that day, the accusations of collusion and cover-up, and the fact that the force in the spotlight is South Yorkshire Police – the constabulary that failed at Hillsborough and sought to smear the victims – mean that the pressure for some form of inquiry into what happened at Orgreave is growing stronger. In fact, the Independent Police Complaints Commission found recently that the same senior officers and police solicitor who dealt with the aftermath of Orgreave also dealt with the fall-out from Hillsborough.

But what did happen at Orgreave? It is alleged that – three months into the miners’ strike – the police allowed several thousand miners to converge on the village that was home to the coking plant that supplied the British Steel furnaces in Scunthorpe. Ordinarily, they would have been prevented from reaching Orgreave but, it is alleged, the police pre-planned a confrontation that they hoped would smash the National Union of Mineworkers and bring about the end of the strike. The officer in charge of the policing operation at Orgreave, Assistant Chief Constable Clement, later gave credence to this claim: a year after the event he said publicly that if there was going to be a battle between the police and the miners, he had decided he wanted it “on my own ground and my own terms.”

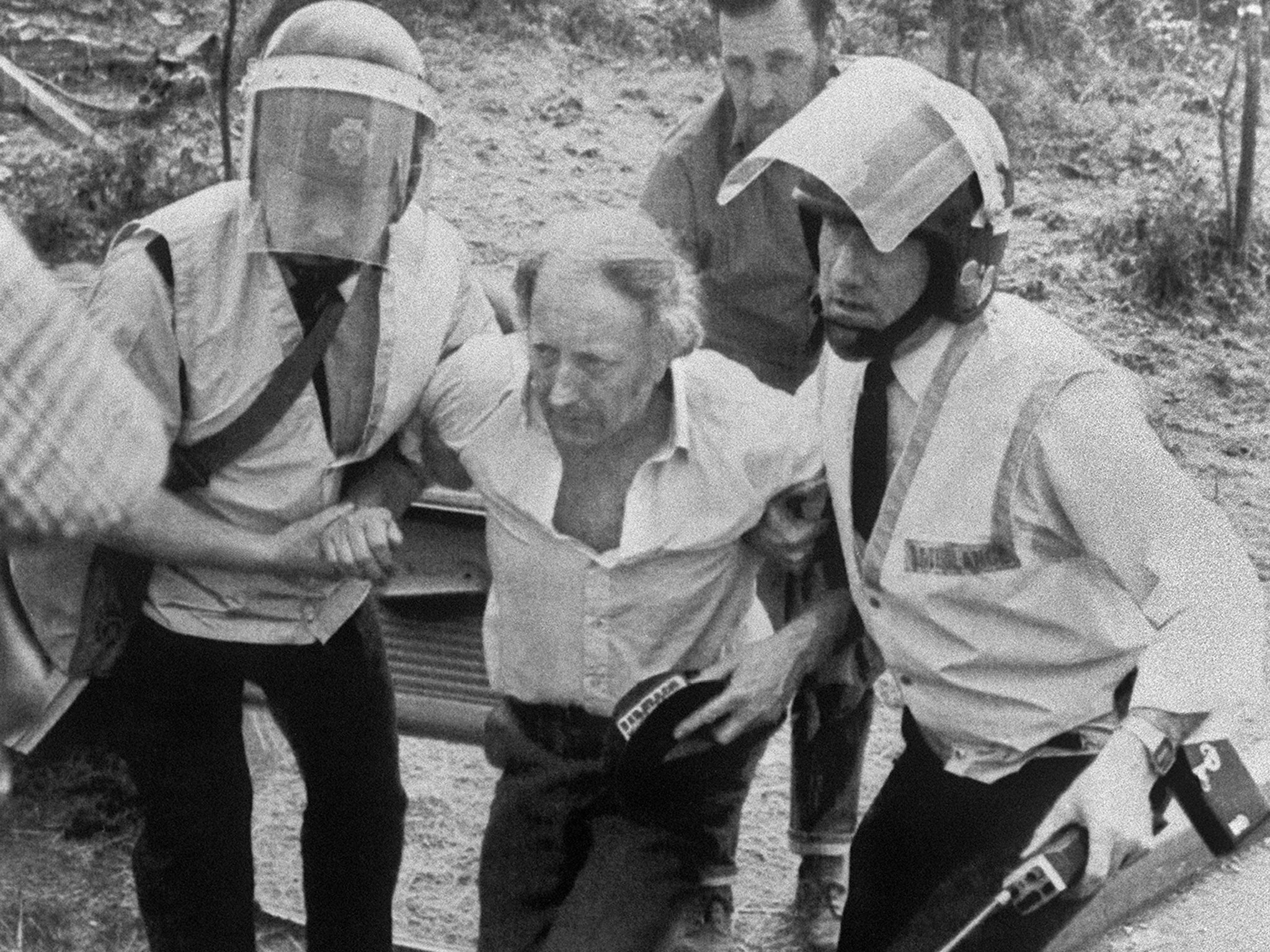

Footage from a police film of the operation apparently shows the miners being led to an open field, where they were allegedly kept in a cordon maintained by police dogs. It is claimed that police horses galloped through crowds without warning, and people who did not get out of the way were trampled, arrested and charged with riot. For the first time in mainland Britain, ‘short shield’ police units were deployed, and many miners were said to have been struck over the head and body by police officers who wore boiler suits and had allegedly removed their identification numbers. The police were acting in accordance with a manual produced by the Association of Chief Police Officers called ‘Public Order Tactical Options’, which allegedly endorsed violent tactics that would allow them to “incapacitate” demonstrators, even though the law said that the use of such force could only be allowed in matters of self-defence or the prevention of crime. Some witnesses even allege that many of the men in police uniforms were not police officers at all, but army soldiers.

The police, for their part, maintained that they were only upholding the law. The striking miners were using the threat of physical violence to stop the coke convoys getting out of Orgreave and to the steel works in Scunthorpe. They had to use force to clear the area because the miners were throwing missiles at police officers and injuring them. And, as we sit here in 2016 looking back at 1984, we should remember that the miners’ strike as a whole was indeed marked by violence. Those who wanted to go on working were intimidated. Threats were made against the relatives of those who crossed the picket line. People who were brave enough to do so were beaten up. In one incident, a taxi driver was killed after a concrete post was thrown through his car window as he drove a miner to work.

But there are some difficulties with South Yorkshire Police’s narrative of what happened at Orgreave. Of the 95 people arrested on 18 June, nobody was ever successfully prosecuted. In fact, the case against most of the defendants was dropped suddenly and dramatically part way through the trial. Thirty-nine of the men charged at Orgreave brought civil proceedings against South Yorkshire Police for assault, unlawful arrest and malicious prosecution. The police settled all of the cases without a trial or an admission of liability.

A BBC documentary in 2012 interviewed a retired police inspector who said that he and others had their witness statements dictated to them by other officers, just as the police did after Hillsborough. Other officers have said that they were forced to write statements they knew to be untrue. One study of police officers’ witness statements found that many contained sentences that were word-for-word the same as – or at least remarkably similar to – other statements, even though they were written by officers who came from entirely different police forces and who arrested different people. The IPCC has uncovered evidence that suggests that senior figures from South Yorkshire Police knew that officers had perjured themselves in court, but they did nothing about it.

This is why campaigners are so keen to have some form of inquiry into what happened at Orgreave. Of course, some people will argue that as we are talking about events that took place more than thirty years ago, we should let sleeping dogs lie. But the Hillsborough Independent Panel inquiry showed that sleeping dogs in South Yorkshire Police lied, lied and lied again, not just about their own conduct but about the victims and other football supporters. If we want to prevent that from happening in future, if we want to make sure the police are above corruption, collusion and cover-ups, we need to know when and how these things have been allowed to happen in the past. And to know that, we need to investigate cases like Orgreave just the same as we need to look at cases like Hillsborough, Daniel Morgan and Stephen Lawrence.

Doing so should not be prohibitively expensive: the Independent Police Complaints Commission has already been looking into complaints made about police conduct at Orgreave, and the Home Secretary could commission an investigation along the lines of the Ellison Review which uncovered significant police malpractice. Given that the IPCC has found that it is impossible to draw clear conclusions from publicly-available material relating to Orgreave, an Ellison-style review would be a sensible way of establishing the facts before considering whether further steps are necessary.

Neither should getting to the bottom of what happened at Orgreave undermine or repudiate what the Thatcher Government did during the 1980s. The economy needed to be reformed, the unions needed to be faced down, and unprofitable pits needed to be closed. But if the police pre-planned a mass, unlawful assault on the miners at Orgreave, and then sought to cover up what they did and arrest people on trumped-up charges, we need to know.

Because getting to the bottom of cases like Orgreave is the only way in which we can make sure that the police really are the public and the public really are the police.

Nick Timothy is Director of the New Schools Network and a former Chief of Staff to Theresa May.

This piece was first published n the 17th May 2016 on Conservative Home

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments