Stumbling Joe Biden is no longer just America’s problem

The ‘President Putin’ gaffe at the Nato summit was the moment Biden’s re-election bid died, says Mary Dejevsky. Now, the Democrats’ political crisis will have diplomatic implications far beyond the corridors of Capitol Hill

The 75th anniversary Nato summit was seen as the test of Joe Biden’s fitness for presidential office, after last month’s televised debate that went so badly wrong.

It was less the two-and-a-half-day gathering itself – which expert planning would ensure ran pretty much glitch-free – but the US president’s hour-long solo press conference that was scheduled to follow, which would be the first time since that fateful debate that he would have to face sustained questions and give spontaneous answers.

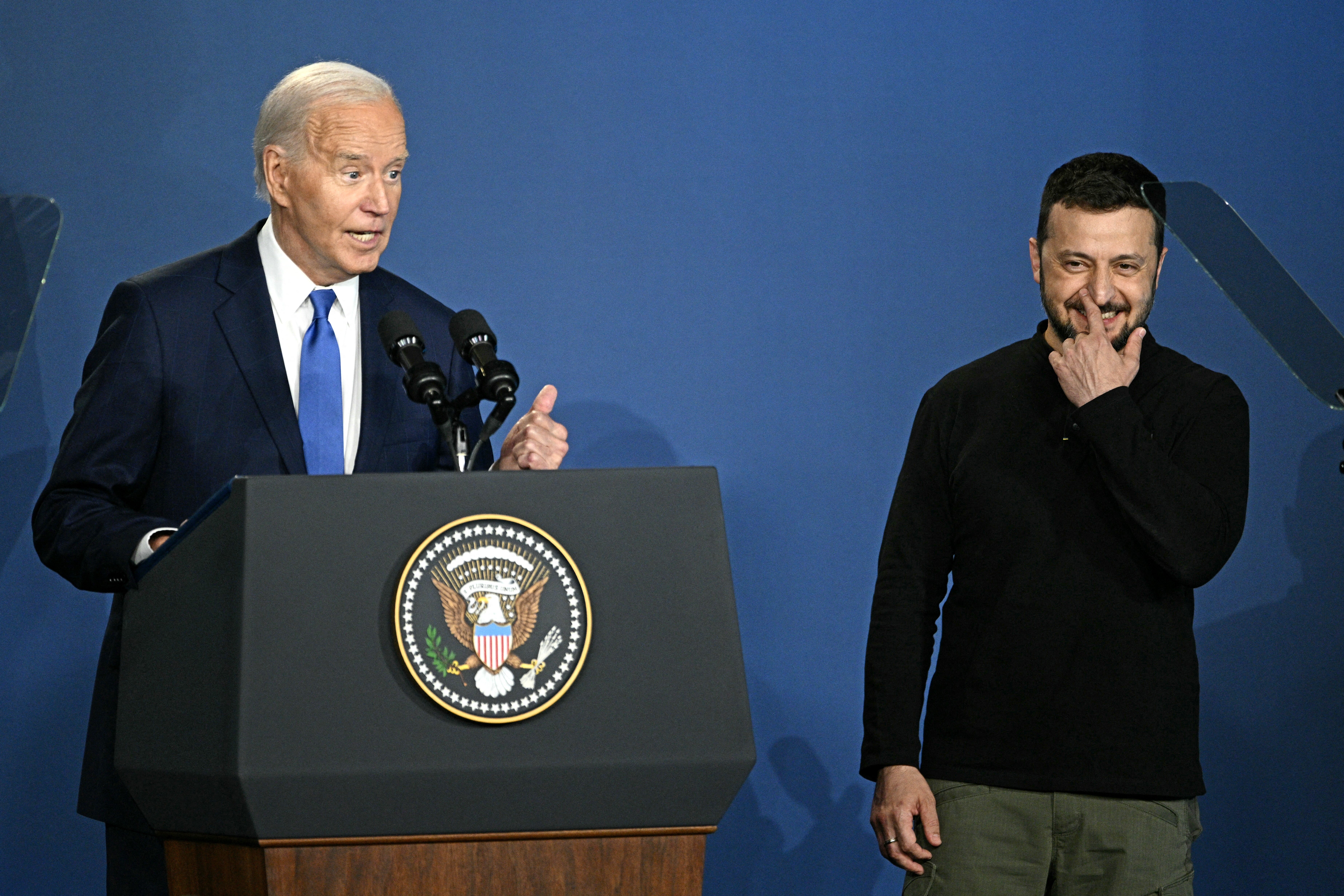

In the event, the growing number of those calling on Biden to abandon his bid for re-election had their scalp even before he had tried almost too hard to stride presidentially onto the platform for his duel with the world’s media. Just a couple of hours before, he had made what seemed the most extraordinary gaffe, when he addressed Ukraine’s President Zelensky, in his presence, as... “President Putin”, before correcting himself after shocked prompts from reporters.

Now, forgetting names is not a cardinal sin, and – in the greater sum of things – nothing that, of itself, would exclude someone from the highest office. But to confuse the names of your chief protege and your chief adversary, in the presence of the former and in front of the world’s cameras, is quite a gaffe; one that betrays perhaps not only a common effect of advancing age, but how large Putin looms in the mind of the US president at this stage of the war in Ukraine. No wonder Zelensky, never the most patient of individuals, cancelled his own planned press conference, although whether he was wise to do so is another matter.

The “President Putin” gaffe meant that almost however well Biden withstood his ordeal by press conference, there was a sense in which he had already failed. Without that fleeting episode, Biden could have left the press conference with, at best, some of the damage from the debate repaired and, at worst, relatively unscathed. He grasped and answered the questions put to him; he was sufficiently in command to allow himself some discursive answers; and he addressed, albeit with more lightness than was perhaps appropriate, the age and competence issues.

His speech and demeanour might be slow compared with someone younger – or, indeed, compared with his 78-year-old Republican rival for the presidency. But it could be argued that Biden has never been the most eloquent or quick-fire speaker, that steadiness and taking time to consider are desirable qualities in a political leader, and that he had been able to lay at least some of the concerns about his acuity to rest.

The gaffe, which was on camera and has subsequently dominated the news from Washington, made that impossible. His advocates can claim, not unreasonably, that this is unfair, that it is taking a momentary lapse out of all proportion, that we could all do it. But that is how it is.

The impression a leader creates counts for as much as the substance. Those in the spotlight, and their staff, have to ensure that the two match up. In that one moment, there is a risk that Biden has given succour not only to those calling on him to make way for another Democratic nominee to fight the November election, but on whether he can remain in office for the six months that remain until Inauguration Day.

The difficulty this time is that the potential damage goes further than the United States. The televised debate that amplified appeals from other Democrats for him to step aside in favour of another candidate, even as it appeared to strengthen his determination to carry on, could be seen primarily as a domestic issue. Even more narrowly, it could be seen as an issue dominating corridor talk on Capitol Hill and exercising commentators in the national media, but not really provoking any broader national or international conversation, still less having any immediate diplomatic implications.

That has now changed. The Nato summit was Biden’s chance to show the world a president in command, who was worthy of their confidence into the election and on into another term. How many of the 32 Nato leaders – plus the leaders of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea, who were also in attendance – will have come away with that impression? The Ukrainian president clearly felt insulted, but, given his country’s dependence on US support, was hardly in a position to do much about it.

What happened, however, will have raised or reinforced doubts among the other leaders about the reliability of the current occupant of the White House, and still more about the sense of his seeking another four-year term. Before the Zelensky gaffe, several visiting leaders has passed on reassuring impressions of their face-to-face meetings with Biden – including Keir Starmer, who nabbed the Oval Office meeting coveted by every new UK prime minister in record time.

It will be instructive to watch, however, how their experience of those days in DC could play out, now that the visiting leaders have gone home. As they paid court at the acknowledged centre of Western power, what did they really find at this centre? An elderly man, mostly – to all appearance – still just about competent and mostly in control, but visibly and audibly slowing up and susceptible to mixing up names when it really mattered; in the high-stakes press conference, he also referred to Kamala Harris as “Vice-President Trump”.

The world has suffered the effects of leaders in their dotage before: Roosevelt at Yalta; Churchill suffering a stroke during his second period in office; the succession of infirm Soviet leaders in the early 1980s. And democratic systems, at least, have institutions and supports that can, to a degree, save such leaders from themselves, and their countries from the catastrophic mistakes that could result.

That is no reason to prolong such a state of affairs. The prospect of a leader seeking presidential power for another four years, when his health and awareness are already short of 100 per cent, is a liability for the country concerned and for its allies. It becomes a positive danger when that country has the capability to annihilate another at the flick of a switch, and the leaders of those countries that might be deemed international competitors, if not actual enemies, exhibit no such weakness: Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, and even, with health rumours in the past, Vladimir Putin.

The US may or may not be a power in decline. But for the foreseeable future, the president of the United States is a global figure. As such, it is not enough for him to be just about capable of doing his job; he needs to be seen to be capable of doing it. In Washington this week, despite Herculean efforts, Joe Biden failed that test.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments