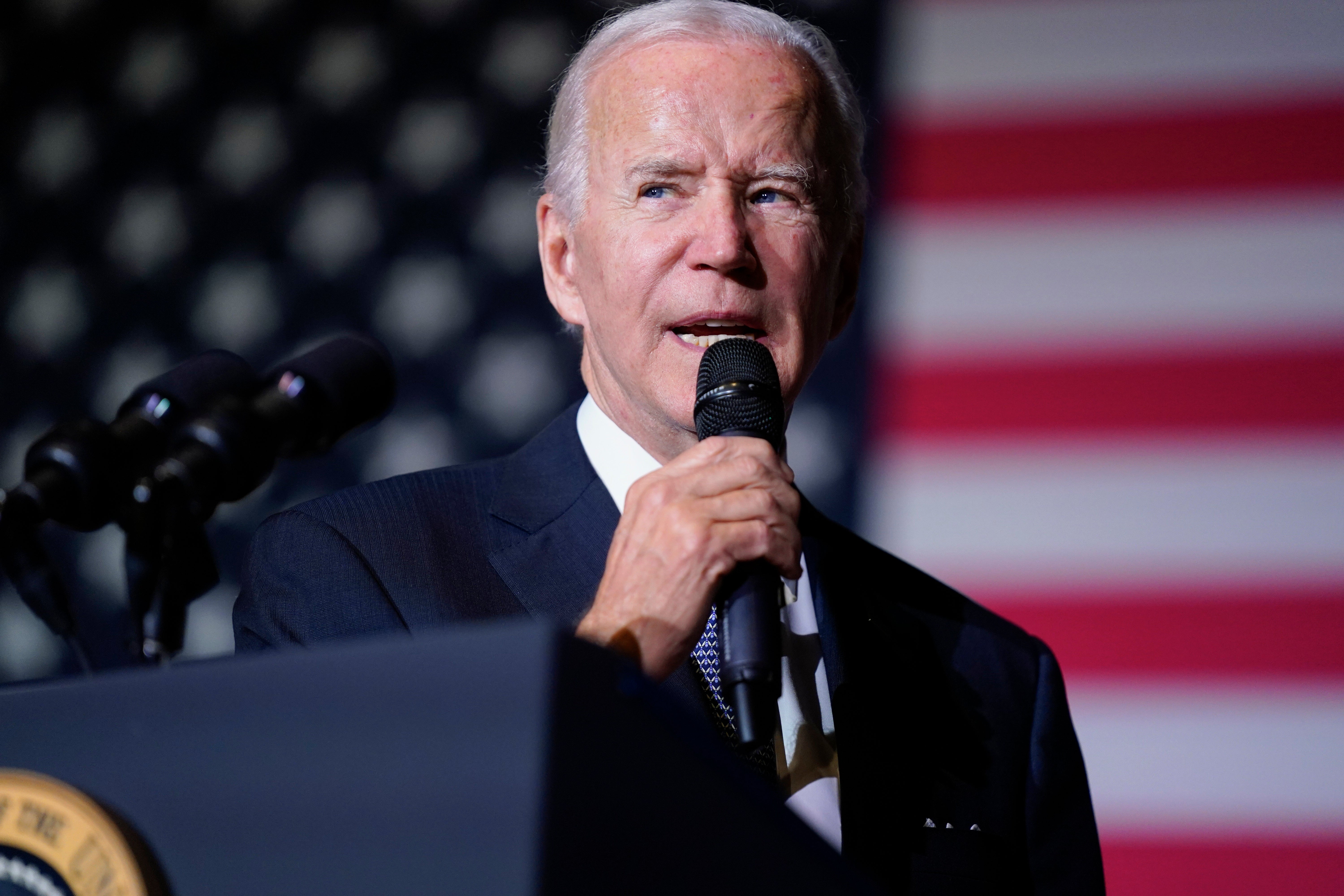

It’s ‘angry Joe’, not ‘sleepy Joe’ – don’t be fooled by Biden’s ‘nice guy’ image

What do reports of the US president’s temper tantrums suggest about angry men in politics, asks John Rentoul

One of the worst-kept secrets of Washington is that Joe Biden has a short fuse. According to Alex Thompson, who is writing a book on the president, “behind closed doors, Biden has such a quick-trigger temper that some aides try to avoid meeting alone with him”.

The president is prone to shouting and swearing at staff, and “there is occasionally a menacing and humiliating tone to his diatribes”, Thompson said.

Should we be surprised that Biden’s character in private is more aggressive than the genial geriatric persona he puts out? There have been hints of a sharper side to Biden’s personality in previous books about him. As one of the longest-serving politicians in the world – he was senator for Delaware at the age of 30 in 1973 – he has been reported and written about more than most.

He won the election against Donald Trump partly because he was considered more decorous, less given to whims and rages than his opponent. Because of his sheer length of service, he was regarded as an old-fashioned, courtly gent, but it should be obvious that anyone who has succeeded in politics that long must be more forceful than he usually appeared in public.

Even so, leaders can be forceful without intimidating and humiliating the people around them. Indeed, my view is that courtesy and an equable temperament tend to be associated with the most effective politicians. The model among recent US presidents was Barack Obama. Not only did his cool personality help secure healthcare reform, but it helped to civilise public discourse throughout the English-speaking world.

George Bush Sr had some of the traditional virtues associated with Biden’s public persona, and by all accounts was level-headed in private too. The younger Bush, although he had a more brash exterior, was not a shouter or a thrower of things in private meetings. Bill Clinton was a more volatile personality, and a good campaigner, but a less successful legislator.

Among British leaders, it may not be a coincidence that the two longest-serving prime ministers, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, were known for their politeness and consideration in their dealings with their colleagues. Roy Jenkins insulted only himself when he damned Blair with faint praise, saying that he had a second-class mind but a first-class temperament.

It was that temperament that helped Blair prevail for so long over Gordon Brown, the archetype of the opposite personality – the angry man who gets his way by intimidation and fear. Quite often, this kind of personality inspires a peculiar kind of loyalty from their aides – people who regard putting up with otherwise unacceptable behaviour as the price of greatness. Several people who worked for Brown, and who still admire him, would recognise Thompson’s description of Biden’s long-serving coterie who “made the calculation that his virtues outweigh his faults”.

But you do not have to be an angry man to succeed in politics; you do not even have to be a man. Despite her public image as a warrior leader, Thatcher’s solicitousness towards colleagues and the most junior of staff was the stuff of legend.

Theresa May wasn’t in No 10 for long, which may not have been her fault, but she tended to get her way by the tactical deployment of silence rather than by shouting and swearing.

Of the five prime ministers that the Conservative Party has delighted the nation with since 2010, David Cameron was a smooth operator and lasted the longest. Boris Johnson was given to petulant rages, not usually aimed at others, but more often at either the universe for its unfairness or at himself. His private demeanour was often at odds with the joviality of his public performances, but his weaknesses as a leader lay in a different direction from his occasional rants about his ministers – Dominic Cummings, for example, published Johnson’s WhatsApp message describing Matt Hancock, the health secretary, as “totally effing hopeless”.

After the parliamentary Tory party reversed out of the Liz Truss diversion, it ended up with another prime minister with a first-class temperament, but Rishi Sunak has probably taken over a hopeless situation too late in the day. Even so, if the Tories are to have a chance at the next election, his brand of Blairite reasonableness and courtesy can only help.

Just as, in a mirror image, President Biden’s temper tantrums may hinder his quest for re-election. Not because, as his opponents tastelessly suggest, they are evidence that his mental faculties are in decline, but because shouting at people is not the way to get the best out of them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments