We should not stand by while Palestinian healthcare is decided by Israel’s deeply flawed permit regime

As a doctor, I cannot begin to imagine the pressure on hospital staff to tell parents over the phone that their children have died. That’s why I have urged Jeremy Hunt to bring pressure where it is needed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have recently returned from a medical trip to the Palestinian occupied territories where I met children undergoing treatment completely alone.

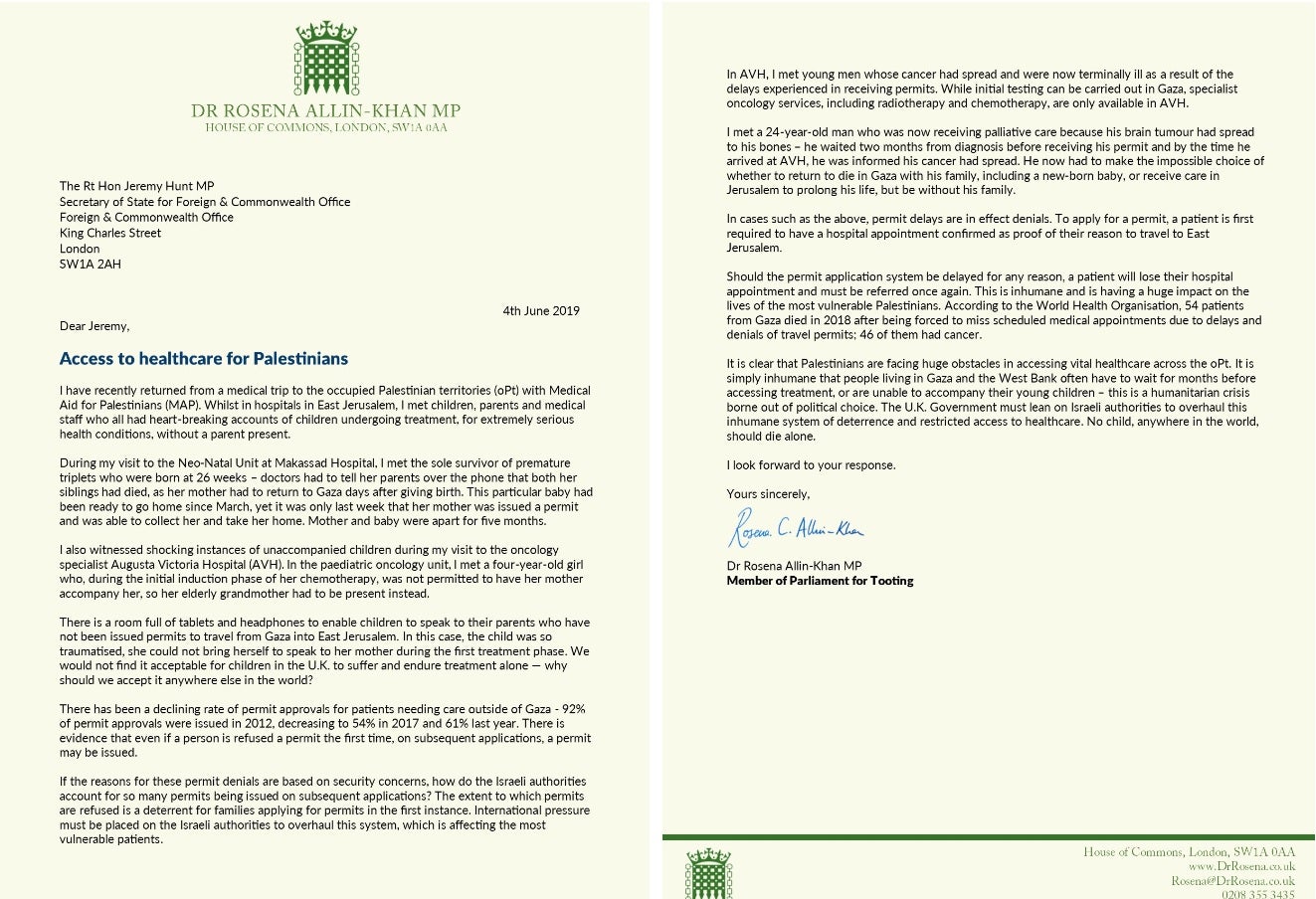

That is why, this week I have written to foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, requesting that international pressure be placed on the Israeli authorities to overhaul the permit system, which is affecting the most vulnerable patients.

During my visit to the neo-natal unit at Makassad Hospital, I met the sole survivor of premature triplets who were born at 26 weeks – doctors had to tell her parents over the phone that both her siblings had died, as her mother had to return to Gaza days after giving birth.

This particular baby had been ready to go home since March, yet it was only last week that her mother was issued a permit and was able to collect her and take her home.

As a doctor, I cannot begin to imagine the pressure on hospital staff to tell parents over the phone that their children have died. As a mother, I cannot imagine how it must feel to be separated from your baby for five months.

In the paediatric oncology unit at Augusta Victoria Hospital, I met a four-year-old girl who, during the initial induction phase of her chemotherapy, was not permitted to have her mother accompany her, so her elderly grandmother had to be present instead. She was so traumatised, she could not bring herself to speak to her mother during those first days.

We would not find it acceptable for children in the UK to endure treatment alone – why should we accept it anywhere else in the world?

With a declining rate of permit approvals for patients requiring care outside of Gaza, more patients are experiencing restrictions on the healthcare they are able to access. And the extent to which permits are refused is a deterrent for families applying in the first instance.

I met young men whose cancer had spread since their initial testing in Gaza owing to the delays they experienced in receiving their permits. They now have impossible choices to make – whether to return to die in Gaza with family, or receive care in Jerusalem to prolong their lives, but without their family at their bedsides.

In such cases, permit delays are in effect denials.

Should the permit application system be delayed for any reason, a patient will lose their hospital appointment and must be referred once again. This is inhumane and is having a huge impact on the lives of the most vulnerable Palestinians.

It is simply unacceptable that people living in Gaza and the West Bank often have to wait for months before accessing treatment, or are unable to accompany their young children – this is a humanitarian crisis borne out of political choice.

I would hope that the UK government will work with Israeli authorities to overhaul this inhumane system of deterrence and restricted access to healthcare. I will continue to raise this with the foreign secretary at every available opportunity.

No child, anywhere in the world, should die alone. No one should face these shattering choices.

Rosena Allin-Khan is Labour MP for Tooting and an A&E doctor at St George’s Hospital

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments