Isis executes Palmyra antiquities chief: Defender of ancient city's past was killed for protecting its future

After a month, the militants realised that Khaled al-Asaad knew nothing – or would say nothing – and so they decapitated the old man and strung his torso to a Roman pillar

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

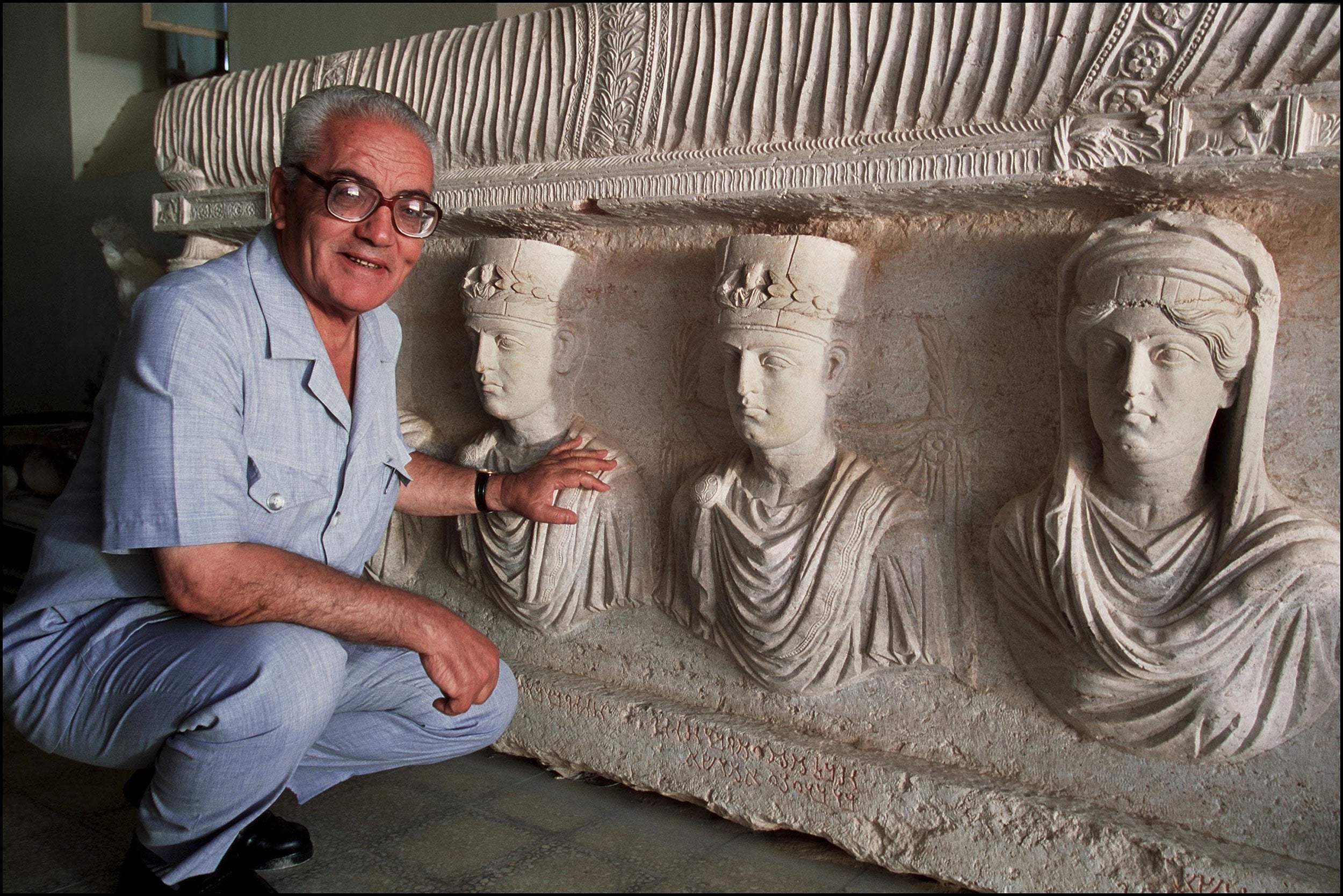

Your support makes all the difference.Isis has killed “the guardian of Palmyra”. Tortured for a month and then beheaded for refusing to betray the secret location of the Roman’s city’s priceless artefacts, Khaled al-Asaad’s gruesome death has appalled his fellow archeologists.

“[He was] a joyful guy. You had to see him if you went to Palmyra. He was a guardian of the past,” a Lebanese archeologist, Joanne Farchakh, recalled. “You felt his passion when he talked.”

The 82-year old was long retired, remaining at home when Isis descended on Palmyra three months ago. What would the “Islamic Caliphate” want with an old man steeped in antiquity? Certainly no tour of the Roman forum and amphitheatre, the remains through which he walked with countless foreign archeological teams over half a century, ensuring – as Ms Farchakh said – “that they made no mistakes, didn’t get the facts of history wrong”.

In truth, Mr al-Asaad knew that most of Palmyra’s movable artefacts had long ago been taken to the comparative safety of Damascus (no one could transport the entire Roman city away), but Isis believed he knew where other treasures might have been buried.

After a month, the fighters realised that Mr al-Asaad knew nothing – or would say nothing – and so they decapitated the old man and strung his torso to a Roman pillar in the ancient city.

He had, in his long career as a civil servant, visited overseas archeological conferences, and this alone would have merited a death sentence in the eyes of his puritan torturers. If you work for the Syrian government, in however lowly a role, you are a “regime man”.

For months, Isis has operated an antiquities smuggling ring, selling objects from Syria’s Roman past to international dealers, usually through Turkey.

“Khaled al-Asaad was always there, and then he became a hostage,” said Ms Farchakh. “The truth is that Palmyra is a hostage itself – to two wars and to two political systems.”