The report into abuses at Ireland’s mother and baby homes does not go far enough – there must be criminal justice proceedings

Tuesday’s report contains harrowing details of what happened at 18 homes but must not be seen as a substitute for the justice procedures of a democratic society

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

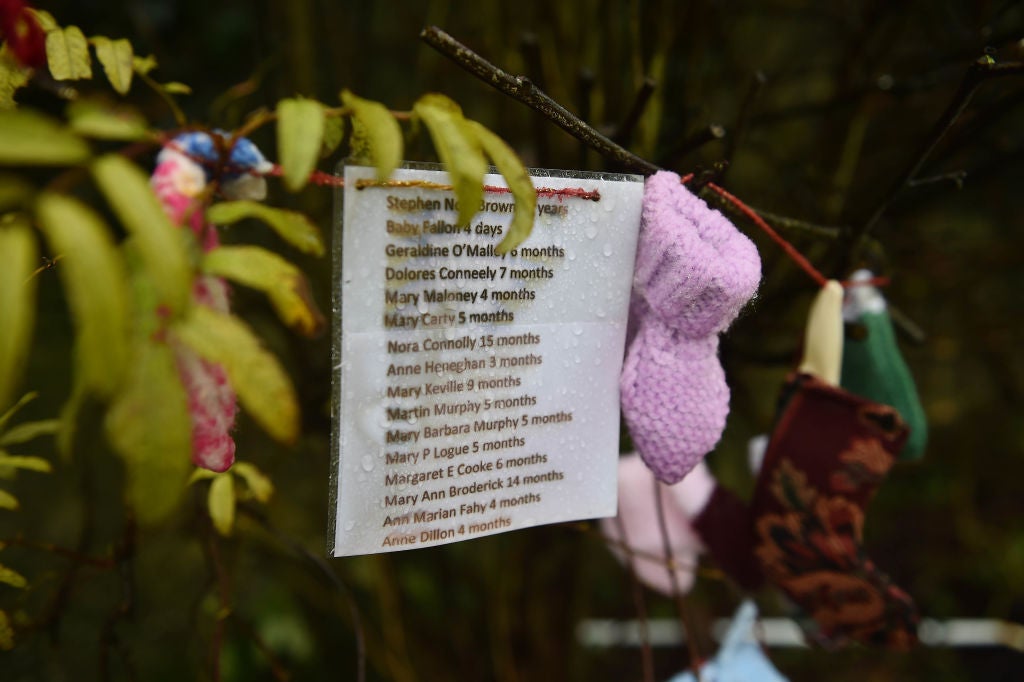

Your support makes all the difference.In 2014, historian Catherine Corless made headlines with the findings that up to 796 children’s bodies lay in an unmarked mass grave in a septic tank on the former grounds of a Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway, Ireland.

While national Irish media were slow to take Corless seriously, the robust nature of her evidence prompted a survey of the site of the grave and proved her correct. A commission of investigation into Ireland’s Mother and Baby Homes was launched in 2015. On Tuesday, it delivered its final report.

The report contains harrowing details of what happened at the 18 homes under investigation. Perhaps its most shocking revelation is that 9,000 children died within the system – approximately 15 per cent of all the babies born there. Towards the end of the almost 3,000 page report, there are 180 pages of witness testimony, which paint a horrifying picture of coercion, control, and abuse.

On Wednesday, the Irish Taoiseach issued an apology to survivors, saying, rightfully, that “the shame was not theirs; it was ours”. While this state apology is important, the Taoiseach’s speech historicises the lack of respect for the dignity and rights of survivors. This trend continues across Irish political discourse, where emphasis is on closing a dark chapter in Ireland’s history. But survivors of Mother and Baby Homes and Irish adopted people are still not being listened to. They are still being denied their rights.

The report was leaked before survivors had a chance to be briefed on it at a webinar on Tuesday. Accounts from the webinar tell of confusion and disappointment, as the report laid blame for the treatment of unmarried mothers and their children at society’s door. Everyone is to blame, and thus no one is to blame – certainly not the church that ran, or the state that funded, inspected, and licensed these abusive institutions.

The most oft-repeated refrain of the report is “no evidence”. In spite of the testimony of women, such as Terry Harrison, who were brought to homes against their will by priests and nuns and incarcerated there, the report concludes that there is no evidence that the church or state forced women to enter these institutions. In spite of witnesses’ stories of pregnant women being slapped and punched by nuns for not working hard enough, or of children beaten until bleeding and unconscious, the report finds little evidence of physical abuse. In spite of the insistence of mothers that they did not consent to giving up their children, the report finds no evidence of forced adoption. And in spite of the ignored recommendation of survivor Rosemary C Adaser that the commission employ an expert on race to understand the experiences of children of colour and Traveller children, the report finds no evidence of racism.

On the subject of the church’s failure to comply with the investigation, there are but brief reprimands. It is frustrating, the report finds, that the church will not give any information as to where the bodies of the over 900 children that died at Bessborough might be found. It can find no evidence that there were significant sums of money involved in sending babies to the US to be adopted, but then, it is the opinion of the commission that access to the administrative records of the congregations that arranged such adoptions be governed by the religious themselves.

Archivist Catriona Crowe disagrees. She says that when, as in Ireland, the church was in charge of providing public services, it acted as a type of state entity, and its records should be publicly available.

As to the report’s descriptions of the vaccine trials carried out on vulnerable children, you would swear that the trials were unattributable to any actors and entirely unprofitable. Perhaps it was society as a whole that allowed multinational corporations like Glaxo Wellcome to medically experiment upon these children? The commission asserts there is no evidence of harm from the trials, but it did not investigate to see if long-term harms are evident.

At the same time that the Irish state is apologising for the abuses enacted in these homes, it is also attempting to pass legislation to prevent any inquest into the deaths of the children at Tuam. As the Tuam Home Survivors’ Network says: if you find the body of a child in your garden, the Gardaí (Police) will be called and an inquest will be convened; but if the maltreated bodies of 796 children are found in a cesspit attached to a home run by nuns, the minister for children will bring a bill to cabinet to ensure no inquest is ever held.

Human rights lawyer Maeve O’Rourke of the Clann Project says that this report is not a substitute for the justice procedures of a democratic society. The investigation was conducted in secret, in a manner completely incompatible with international best practice for inquiries into human rights violations. Those affected had no access to evidence or their own records; they could not testify publicly or suggest modes of enquiry. Despite government assurances that survivors have the legal right to access their records, the commission of investigation is still denying any requests for information. In short, survivors and adopted people continue to be treated appallingly.

The deaths at Tuam need to be investigated. Access to personal information – including birth certificates – needs to be unequivocally granted. Criminal justice proceedings need to be facilitated by the state. In short, the law of the land needs to apply to what happened in Mother and Baby Homes and in Ireland’s secret and illegal adoption system.

Tuesday’s report does not close a dark chapter in Irish history. Rather, it opens a book filled with fragments and missing pages, with many vital details redacted and a narrative voice that comes to feel less trustworthy the more you read. This story is still being written, and we must support survivors as they continue their fight for justice.

Dr Emer O'Toole is associate professor of Irish Performance Studies, School of Irish Studies, Concordia University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments