I stayed in Iran during the last days of the Shah. What I saw is particularly important to mention now

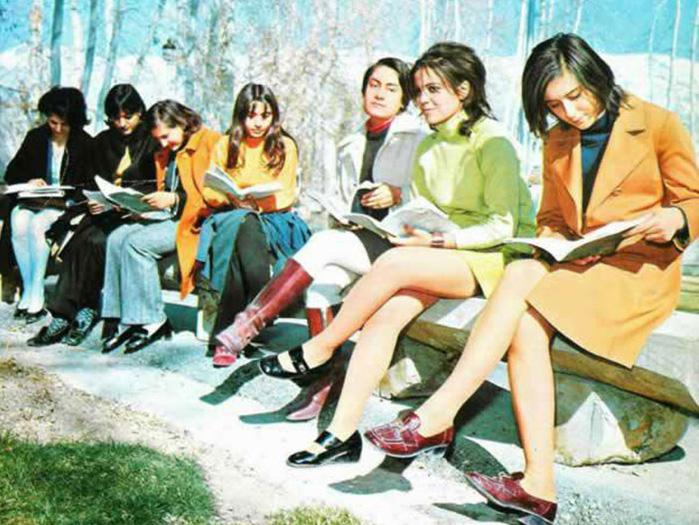

Back when women who wore heels and lipstick regarded their chador-clad sisters in the religious cities and the countryside as backward, Iran was supposed to be on course to becoming a reliable ally of the West

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So that, it would appear, may be that. As Iranian city streets filled with pro-regime demonstrators, the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard declared the “defeat of sedition” – by which he meant the past week of protests. But is what many saw – wishfully, perhaps – as the most serious threat to theocratic rule since the ayatollahs came to power really over, and was it that serious anyway?

The very use of the word “sedition” certainly amounted to an admission that the unrest had passed beyond a revolt against economic grievances, to acquire more than a tinge of the Green Movement protests that broke out after the 2009 presidential election. Not only that, but the complex of motivations had something of the sadly misnamed Arab Spring. Is Iran, with its overwhelmingly young population, its frustrated youth, and the double blight of Western sanctions and low oil prices, simply a decade or so behind the regional curve? If so, will the anti-regime protestors fade away, or will they regroup and return – not this week or next, perhaps, but in months or a year?

So much of history depends on where you start from and the lens you are viewing it through. And any interpretation of the latest protests in Iran is no different.

For those who “came in”, as it were, after 1979 when the Islamic Revolution that swept Ayatollah Khomeini to power, they can indeed be seen as the first serious threat to theocratic rule, both by virtue of the political complexion they assumed and the rapid and wide geographical spread. They were not just, as some have argued, like a reprise of the provincial food protests of early 1990s. There seems to be – or to have been – more to them than this.

My perspective, however, is a little different. I spent a summer in Iran in the early 1970s, when the Shah was still in power, American backing for the regime was visible and an Islamic uprising was (barely) on the radar. Younger city women worked and wore heels and lipstick and regarded their chador-ed sisters in the religious cities and the countryside as backward. The assumed trajectory – assumed that is by Iran’s urban middle class, by foreign investors and by the UK and Washington – was that Iran was rapidly modernising and would take its place as a leading, and reliably pro-Western, regional power.

Within the decade, that prospect was gone. And in 1978-79, watching the television footage of mass demonstrations in the south of Tehran and the triumphant return of Khomeini, I remembered some other details of my Persian summer, when I had stayed with, and been shown the country, by my formidable aunt.

Mary Isaac was headmistress of a charitable girls’ school in Isfahan, a character made of the same sort of determined and pioneering stuff as the solitary female travellers of earlier years. She had aspired to be a Christian missionary in China, but the missions there were being closed, and she was assigned to Persia instead. By the time the Shah nationalised education and declared that all school heads (among others) had to be civil servants, she was more educator than missionary, and was granted Iranian citizenship to continue her job.

When I visited, she was living in retirement in a flat in the precincts of “her” school, more Iranian in many ways than British. She even adopted an Iranian girl.

What I recalled in 1979, though, was this. She despaired of the impracticality of many of the new educated middle class, their condescension as she saw it towards their uneducated compatriots, and their refusal to become involved in politics, which left the field clear for clerics and the corrupt. She was also acutely aware of the authority wielded, largely invisibly, by the mullahs. That, she told me, nodding towards a small group of berobed and turbanned clerics conversing at the entrance to the bazaar, is where the real power lies.

She also took me into the depths of the countryside, where mores and conditions were essentially biblical. The gap between rich and poor, between those with education and without, between north Tehran’s Westernised “fast set” and the shanty town that stretched as far as you could see on the city’s southern rim – and gave Ayatollah Khomeini his mass support base – was obvious.

It never occurred to me at the time, and perhaps not to my aunt either, that the process of westernising – widely seen as synonymous with modernisation – would be eclipsed, either at all or for the early four decades it has been since Iran’s Islamic revolution.

Nor, I would hazard, did many appreciate how much that modernisation had been fostered from the outside, and how shallow and geographically limited its roots were. The very idea that a popular revolution could be regressive, rather than progressive, was hard to grasp, even though many a revolution can be seen with the benefit of hindsight to hold back development, rather than driving it forward.

Among the lessons I took from the overthrow of the Shah and the victory of an almost mediaeval theocracy was that attempts to impose or accelerate modernisation may be doomed to fail unless there is sufficient support or understanding for what is needed and the benefits spread beyond a privileged caste. The question then is whether Iran’s years under the ayatollahs have created the conditions where at least some of the sharper disparities have been eroded.

This, for me, is the question posed by the protests of the past week. Do they reflect a sudden and brief upsurge of exasperation that can be quelled by a few judicious price subsidies and the continued loosening, within boundaries, of theocratic rules? Or is there now a consensus for change, that could perhaps allow Iran to pick up where it so abruptly left off, though at a slower pace and with fewer of the artificially Westernising impositions?

Any new upheaval in Iran has far-reaching implications in the short term for the nuclear deal, and in the longer term for regional stability (Syria, Lebanon and Yemen) and regional power relationships (Saudi Arabia, Iraq). At best, social ferment could herald a new discussion – at worst, it would descend into a fight: about what sort of country Iran wants to be, and how religion and the state might reach a new accommodation.

With so relatively few, either in Iran or abroad, now having a living memory of a very different Iran, the risk is of a Western lunge in pursuit of gain. Persians have always prided themselves on their long perspective. It is something the often short-termist West could usefully borrow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments