Don’t forget what International Women’s Day is really about – striking

Low income, migrant women working tirelessly as employees, carers, wives and mothers knew withdrawing the work they did would stop the world from turning

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was in 1857, that on 8 March in New York City, garments workers went on strike. Suffering horrific conditions, endless hours and low pay, they took to the streets demanding better money and working conditions. Dispersed after being attacked by police, the women continued to fight and from their movement the first women’s labour unions were established.

In the early 20th century, their movement blossomed. New York City’s streets again saw women march demanding shorter hours, better pay, an end to child labour and the right to vote in 1908. Leading labour organisers sought to strengthen the movement internationally. At the Conference of Working Women held in Copenhagen in 1910, Clara Zetkin asked over 100 women from 17 countries – representing unions, socialist parties and women’s working clubs – to pass a motion for an International Working Women’s Day. They did so, unanimously, and the so International Women’s Day was born.

Zetkin, in conjunction with other well-known women from the movement including Rosa Luxembourg and Theresa Malkiel focussed on the conditions that dictated women’s lives. They organised with women working in inhumane conditions for long hours and no pay. Women who also went home to complete their “second shift” – cleaning, cooking, childrearing and household managing; women who were the engine keeping families, communities, companies and countries running, but whose work received little pay and even less recognition.

It was after the first International Working Women’s Day – a day that saw a million women across Europe take part in rallies – that 140 women’s lives were claimed in the tragic “Triangle Fire” of 1911. Many of them Italian and Jewish migrants, these women died working for next to nothing under atrocious conditions in a New York garments factory. We know, of course, that this is a situation women in the global South endure today.

Rose Schneiderman, a socialist who worked tirelessly to draw attention to conditions that had caused the Triangle Fire, a year later coined the slogan that reverberated across the women’s movement: the demand for “bread and roses”. Demanding that women have the right ‘to live, not simply exist’ in a speech, she said: “The rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.” Five years later, Russian textile workers called for “bread and peace” when they went on strike in protest of the millions of men they knew killed in World War I. Their strike ignited the Russian Revolution.

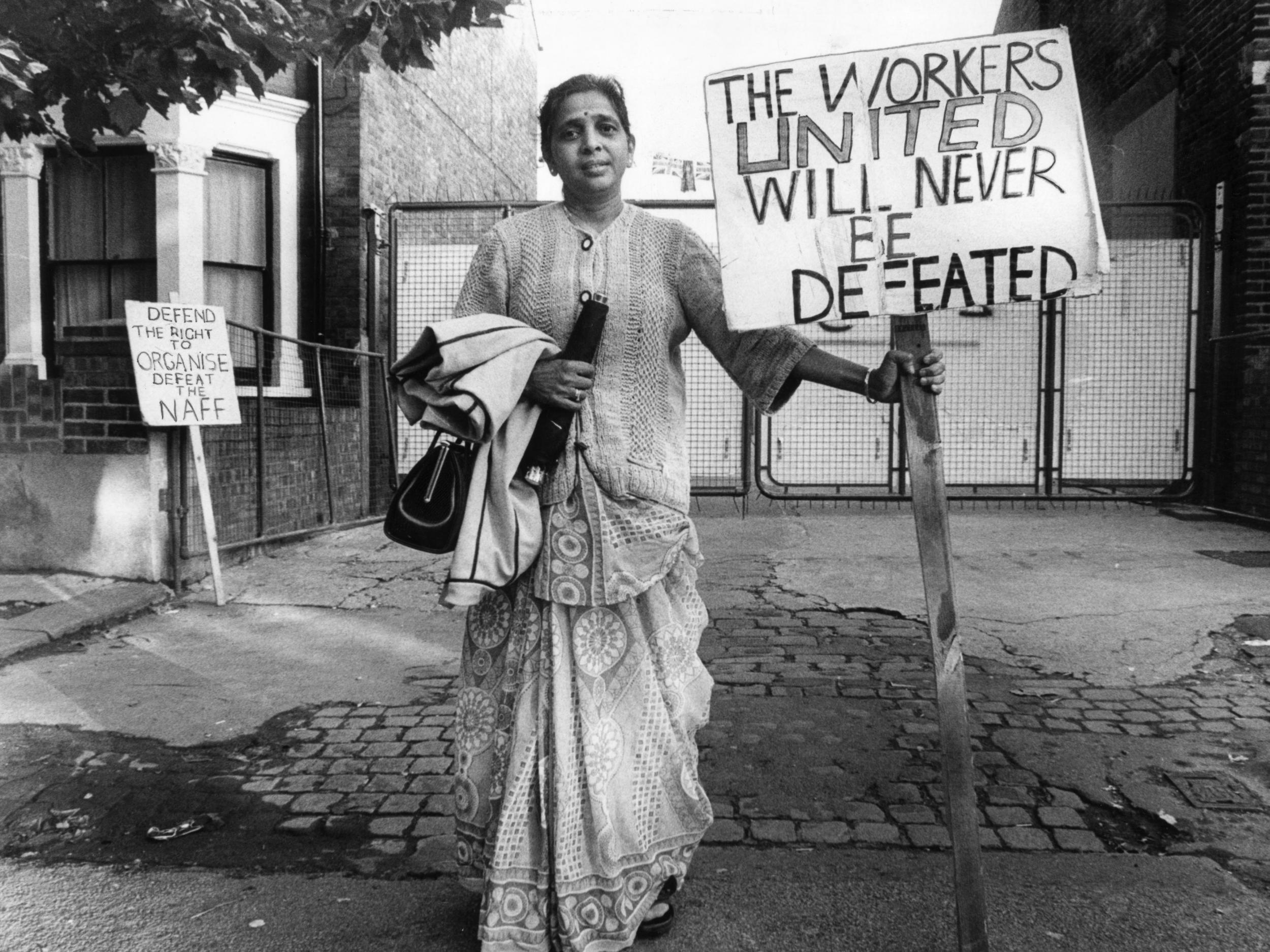

Recurrent across this history of International Women’s Day is one tactic: strike. Women - most often low income, migrant women working tirelessly as employees, carers, wives, mothers, sex workers - knew the power of their labour. They knew withdrawing the work they did would stop the world turning and win them victories.

It is not a tactic lost today. In the tradition of the matchgirls’ strike that birthed the modern trade union movement, the Grunwick and Dagenham strikes that set the foundations for equal pay and migrant workers’ place in workers’ movements, and the Irish women’s strikes since 2000 that marked the founding of the Global Women’s Strike organisation, strikes are having a resurgence.

In the UK, many are spearheaded by grassroots and largely migrant workers. The United Voices of the World, workers enduring horrific treatment and poverty wages from outsourcing firms have organised strikes and won sick pay, holiday pay and in-house contracts. All across this month, too, academics are striking against a raiding of their pensions. This week, with Oxford University backing down, it looks like they are also set to win. And in Yarls’ Wood detention centre, women forcibly detained and driven to work for next to nothing to maintain the centre’s functioning are on strike from work and from food.

For International Women’s Day, too, the strike is back. In 54 countries, women are due to stop work – both paid and unpaid – and take to the streets. Their issues are innumerable: sexual harassment, the denial of trans womanhood, the forcible removal of children from low income and migrant mothers; corporate, street and state racism; poverty wages, benefit cuts, reproductive justice, the decriminalisation of sex work. The women who founded International Women’s Day knew their labour ran the world; they knew the dire conditions of their womanhood would not be remedied with representation, telling their stories, or leaning in – but by action. It is in the tradition of International Women’s Day that this 8 March, we strike.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments