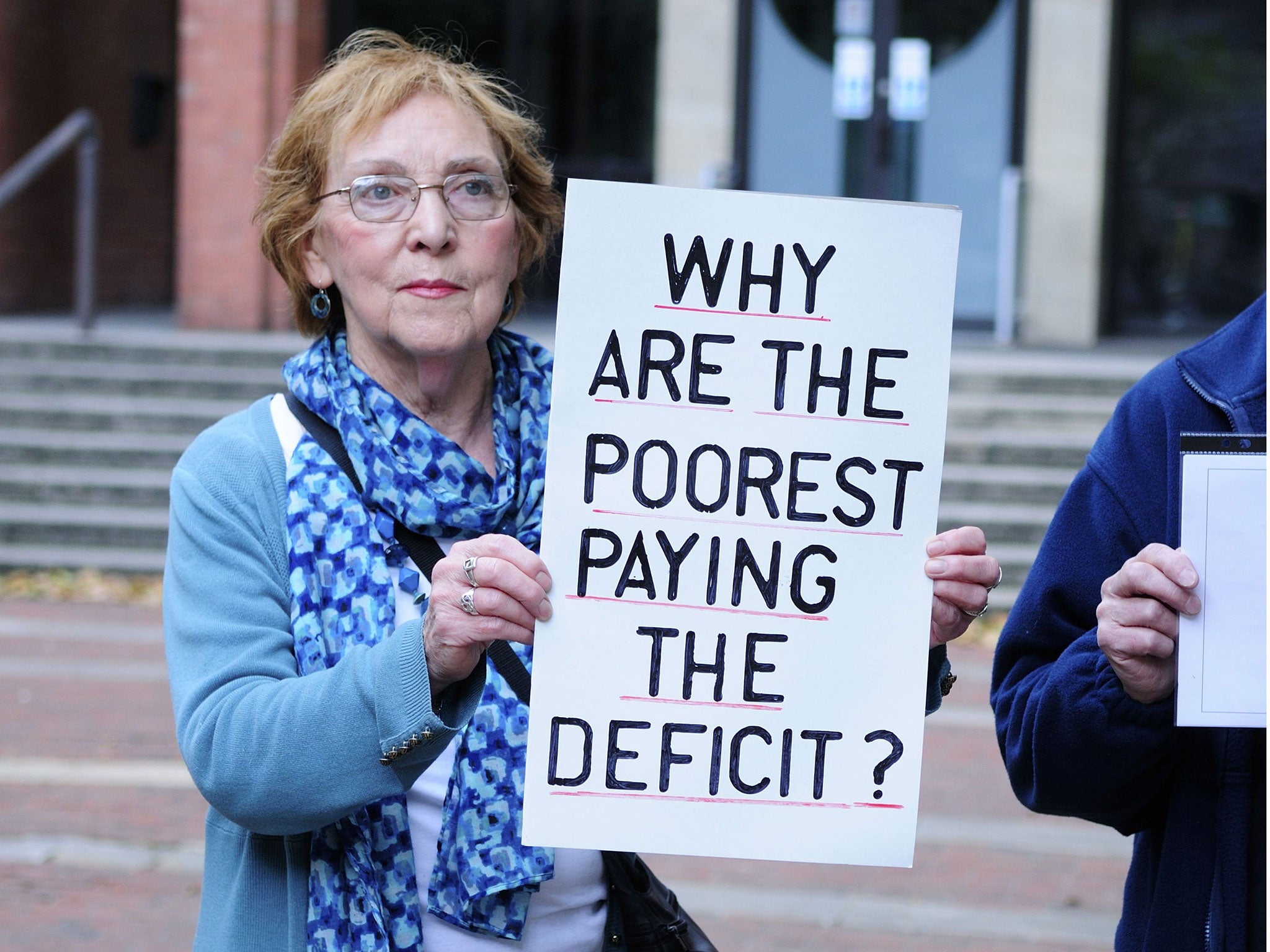

Ingrained bias means civil servants are drawn from a narrow social and economic pool

The Prime Minister needs to put his own house in order before throwing any more stones at others

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In modern Britain, it is getting harder and harder for young people from ordinary backgrounds to move up and get on.

The Government purports to care about this. It set up the social mobility commission under Alan Milburn and claims social mobility is at the heart of every policy it pursues. And in the past two weeks, it has lambasted Britain’s universities over their admission record of black and working class pupils.

But how do we square that with a government that is making it harder not easier for students from ordinary backgrounds to afford to go to university?

It has scrapped Labour's education maintenance allowance, overseen a massive hike in university tuition fees and scrapped maintenance grants for students from poorer households.

These non-repayable grants of up to £3,387 per year were there to help students with the costs of their rent, food and textbooks. In my constituency of Ashfield alone, 690 students benefited from the grants in 2013-14.

But now these grants - which have helped thousands of students from poor backgrounds access university education - are being replaced with loans, putting off thousands of teenagers who do not want to start their working lives saddled with debts.

The Government's rhetoric on social mobility does not match the reality of its policies.

Take another area: recruitment of graduates to the civil service fast stream.

Just over a year ago, I wrote about the shameful under-representation of former state school pupils in the ranks of graduates recruited to the fast stream in 2013.

Black candidates fared equally poorly compared to their white counterparts, as pointed out by former fast streamer, Damian McBride in his own analysis In the wake of the Government’s attack on universities on exactly these two issues, I looked at the latest figures for fast stream recruitment covering 2014, expecting to see a remarkable improvement. Instead, I found them throwing stones from inside a glass house.

First, let’s look at black candidates.

The success rate for black and mixed-race applicants for the fast stream in 2014 was 1.8 per cent, well below the 5 per cent success rate achieved by white fast stream applicants.

Black and mixed-race graduates made up 5.8 per cent of all British fast stream applicants, but just 2.3 per cent of all those who were successful.

So the fast stream is not struggling to attract black and mixed-race candidates – they are applying in higher proportions than they make up the British population – it is just not giving them jobs.

Take the almost 300 applicants to the fast stream of Caribbean origin in 2014. Just five succeeded.

In short, if the government believes the university sector has an issue with black candidates, they first need to take a long, hard look at their own civil service fast stream.

Let’s turn to applicants from state school and working class backgrounds.The success rate for fast stream candidates educated in non-selective state schools was 4 per cent, well below the 5.4 per cent success rate for privately-educated graduates.

Look at the proportions of successful candidates, and the numbers are more stark.

Graduates from non-selective state schools made up exactly 50 per cent of all fast stream applicants, but just 43.6 per cent of successful ones. In contrast, graduates from independent schools made up 18.5 per cent of applicants, but 22 per cent of those who succeeded.

As for students from poorer households, the failures are equally glaring. In 2014, graduates whose parents were in routine or manual employment made up 8.1 per cent of fast stream applicants, but just 4.4 per cent of those who succeeded. In contrast, those whose parents work in higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations were twice as likely to succeed with their applications.

Astonishingly, of 718 candidates from poorer backgrounds who applied for the top graduate fast stream scheme – serving in Whitehall, Parliament or the diplomatic corps – only 8 succeeded.

It does not help that the civil service “summer diversity internship programme” – designed to give students from under-represented groups experience of fast stream work – gives such favourable treatment to applicants from well-off and privately-educated backgrounds.

Applicants whose parents work in higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations made up more than half of those accepted to the programme in 2014; those whose parents were in routine or manual employment made up less than a quarter.

In addition, the success rate of non-selective state school applicants was just 15.3 per cent compared to 25 per cent for applicants from private schools. And this to get on the “diversity programme.”

The civil service is clearly defensive about the accusation that it is not doing enough to recruit candidates from ethnic minority and working class backgrounds.

Its own report on fast stream recruitment says: “If the best people, recruited on merit, do not reflect society at large then we need to look to our education system to provide more support for younger generations to ensure they have the opportunity to become our future leaders.”

So the civil service passes the buck to universities, who in turn pass the buck to secondary schools, who ask what they are supposed to do, and nothing ever gets changed.

The Government talks the talk on social mobility and deserves credit for raising the issue of university admissions. I agree with the Prime Minister when he says that “we must be far more demanding of our institutions, and be relentless in the pursuit of creative answers.”

But where are the demanding questions being asked of fast stream recruitment? Where are the creative answers to their under-representation of black and working class talent?

David Cameron is the Minister for the Civil Service and the simple fact is that – on all the measures on which his government is challenging universities – his own fast stream scheme is currently no better, and in many instances, much worse.

The Prime Minister needs to put his own house in order before throwing any more stones at others. He might not be willing to U-turn on maintenance grants, but his own civil service recruitment would be a good place to start.

Gloria De Piero MP is shadow Minister for Young People and Voter Registration

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments